Actually, Most Americans Are Fine With Jews

So everyone needs to stop pretending otherwise.

I’ve had a few recent pieces maybe of interest to readers. If you’d like my takes on Zohran Mamdani, read me in Pirate Wires and at the City Journal Substack. And if you want me on the recent sports gambling indictments, I’m also at Pirate Wires on those. Edit: As this piece came out, my Free Press piece on the national guard deployments also dropped.

Just over two years ago, I wrote a post on this Substack arguing that “America is Only Going to Get More Divided on Israel.” In it, I used data from Pew’s American Trends Panel (among other sources) to argue that the rising generation was much more divided on Israel than prior generations were, meaning that the then-nascent conflict over America’s relationship with Israel was only going to intensify.

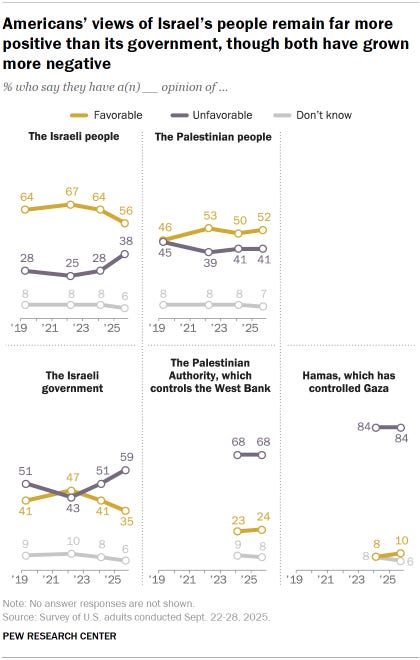

Two years on, I feel comfortable saying that my prediction was basically on the mark, although I should perhaps have moved my timeline up. Only 46 percent of Americans now say they are sympathetic to the Israelis over the Palestinians, the lowest figure on record. The shares unfavorable toward the Israeli government and people have steadily grown. And while self-identified Conservatives continue to lean pro-Israel, those under 50 are evenly divided.1

This post is not about public opinion on Israel. It’s about public opinion on a group everyone closely associates with Israel: Jews. There appears to be strong conviction on the part of both Jews and those who dislike them that the war in Gaza and decline in public support for Israel have shifted American opinion on Jewish people more generally. Has America gotten significantly more antisemitic over the past five two years?

I don’t want to say that the answer is definitively “no,” because a loud and angry minority has done a great deal of harm. I suspect the intensity of antisemitism has gotten stronger in the past several years. But intensity is not the same as extent. And in fact, as this post demonstrates, what was true before is still true: most Americans are fine with Jewish people, or at least feel sufficient stigma around being antisemitic that they won’t admit it when you poll them. And that has, I think, substantial implications for recent debates around antisemitism and Jewish politics.

To show this, below I present some analyses of data from the American National Election Studies, a quadrennial survey administered before and after each presidential election. One of the instruments ANES respondents are administered is a series of “feelings thermometers,” which ask respondents to say how “warm” or “cold” they feel toward a person or other object on a scale from 0 to 100. Specifically, participants are told:

Ratings between 50 degrees and 100 degrees mean that you feel favorable and warm toward the person. Ratings between 0 degrees and 50 degrees mean that you don’t feel favorable toward the person and that you don’t care too much for that person. You would rate the person at the 50 degree mark if you don’t feel particularly warm or cold toward the person.

In addition to asking about warmth toward people, the ANES also administers feelings thermometers for different groups, such as feminists, labor unions, big business—and Jews. I like these data for several reasons. One is that there’s actually (unsurprisingly) little polling about how people feel about Jews (rather than about Israel). Another is that the continuous scale hopefully attenuates (while not entirely obviating) social desirability bias—it’s easier to say you give Jews a 48 out of 100 than to say you don’t like Jews.

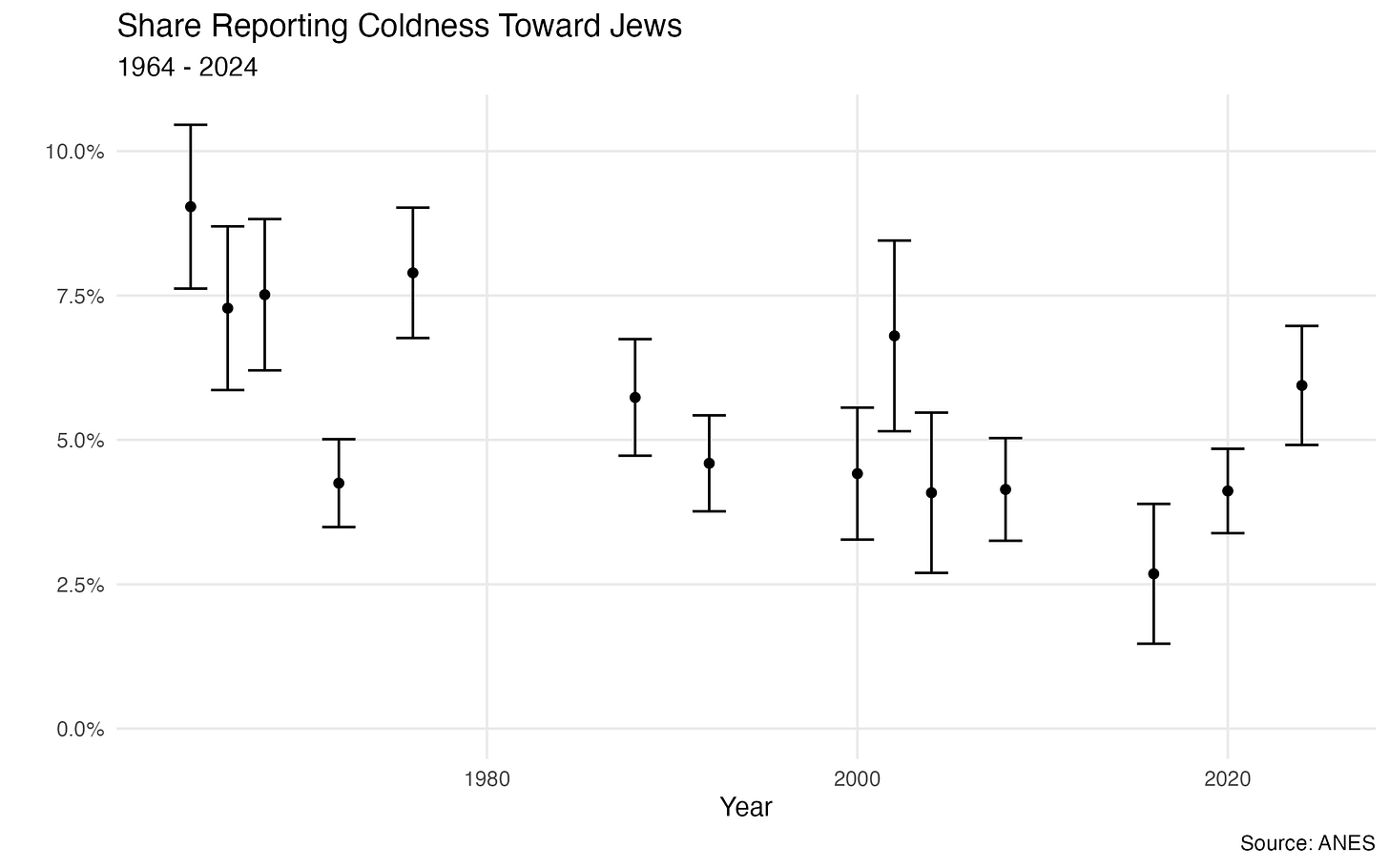

Figure 1, above, plots the share of ANES respondents in applicable waves who report that they feel cold toward Jews (i.e. who gave a response of less than 50). A few observations:

There is a significant increase comparing the 2024 wave to the 2016 wave, and a barely significant increase comparing 2024 to 2020. Focusing just on the point estimates, the share of the population willing to say they feel cold toward Jews is at its highest level since 2004. Omitting that outlier year, it’s higher than at any point since 1976.

In absolute terms, willingness to express coldness toward Jews is still quite rare. The actual rate is less than 6 percent in the 2024 sample.

Recent coldness is about on par with levels in recent years, and notably below those of the 1970s.

In other words: there has been a real but small increase in measurable antisemitism in the period containing October 7, 2023. That increase is on the order of 2 percentage points. That may hide larger real changes, although it’s not obvious to me why the social-desirability adjusted measure would shift more slowly than the real value.

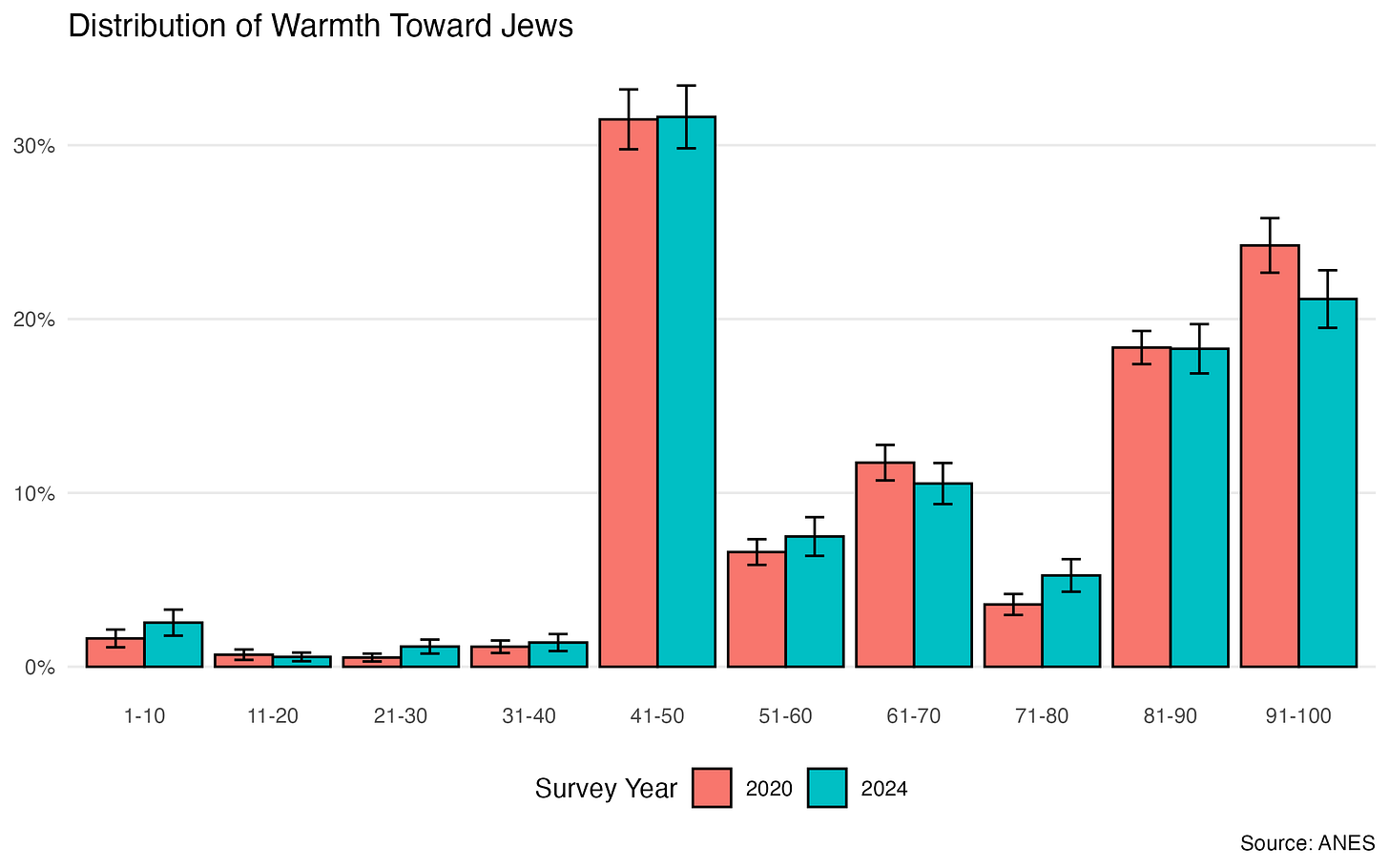

Asking what fraction of respondents are “cold” toward Jews doesn’t give us a full picture of the distribution of responses to the thermometer question. Figure 2 (above) does, allowing us to compare how that distribution changed between 2020 and 2024 (before and after October 7, i.e.). It suggests that there has been some minor shifting in the top half of the distribution — fewer people giving a response between 91 and 100 and 61 to 70, and more giving responses in the 51 to 60/71 to 80 range.

It also shows that most of the growth in coldness comes at the very bottom of the distribution. To break it out, about 4 percent of respondents gave a score of less than 40 in 2020, verus about 5.6 percent in 2024. Most of that change comes in the 1-10 category, which grew by about a percentage point between those two periods.

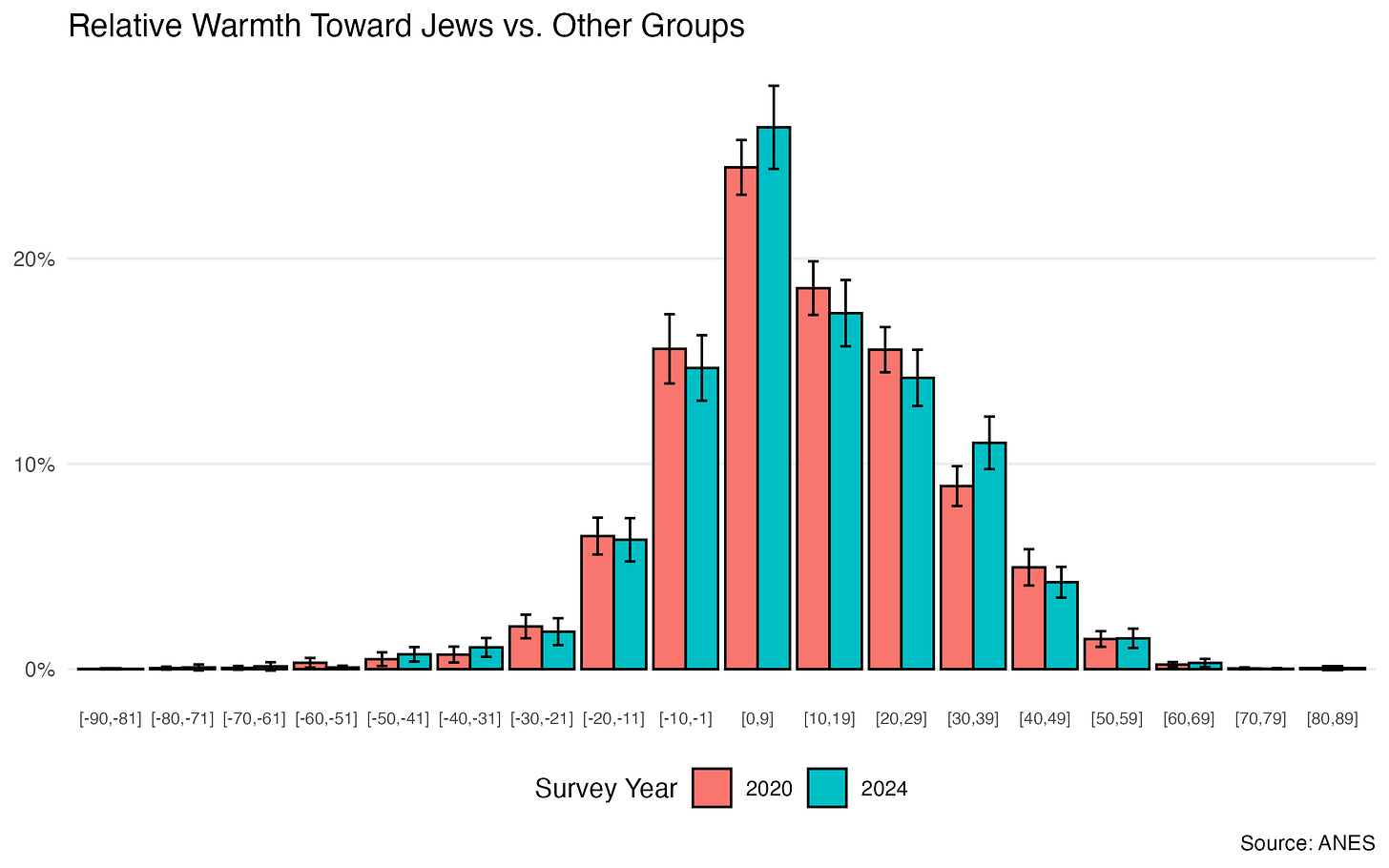

One interesting question these data can answer is how warm people feel toward Jews *relative to* other groups. Relative disposition can be informative: if someone says they are 50 on Jews but 90 on all other groups, we might still think that they have some unusual views about the former.

The 2020 and 2024 ANES include thermometers on a number of other identity groups.2 To construct Figure 3, I take the average of each respondent’s warmth towards those groups, then subtract it from the respondent’s warmth toward Jews. If the resultant value is negative, they’re warmer toward other groups on average than they are toward Jews; if it’s positive, they’re warmer toward Jews than they are toward other groups on Average.

On eyeballing, Figure 3 seems to suggest that Americans are mostly equally warm or warmer toward Jews than they are toward other groups on average. That’s not uniformly true, of course; some are a bit colder, and a few are much colder. But scores are denser on the right-hand side of the distribution, in general, suggesting that many more are warmer than are colder. In other words, more Americans are warmer toward Jews than other groups than are colder toward Jews than other groups.3

The other notable takeaway is that people have gotten, if anything, relatively warmer toward Jews since 2020 (i.e. the right half of the distribution is denser in the 2024 data than in the 2020 data). That suggests the decline in warmth toward Jews since 2020 may represent a decline in warmth generally.

Perhaps these estimates are eliding some change in the population composition that might be more alarming. We tend to think that some people are more likely to be antisemitic than others. Are, for example, the rising generations less philosemitic than predecessors? (This comes up in my Israel opinion post.)

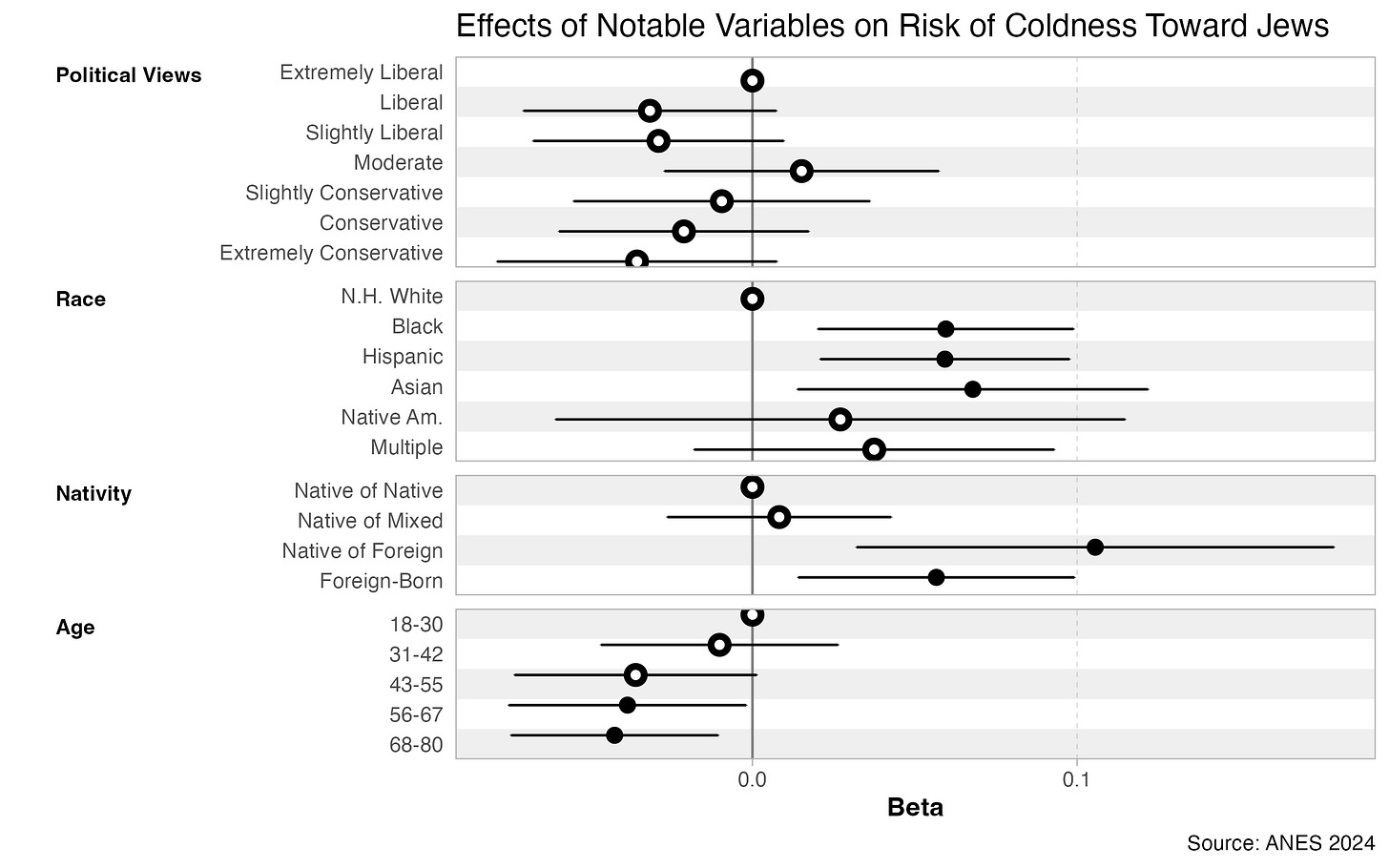

Figure 4 presents the results of a series of bivariate linear probability models4 for a few such variables. In each case, the DV is the probability that someone reports < 50 on the Jewish thermometer question. Note that these are all relative measures: because these are all categorical variables, each has a reference group. So, for example, being in the 68 to 80 age bracket reduces your probability of being cold toward Jews by about 4.2 percentage points. (Keep in mind that coldness is overall quite rare: again, about 6 percent of respondents (± 1 point) were cold in 2024.)

Notably, none of the political view options are significant: there’s some variation, but in general it seems like political view does not have a major effect on coldness toward Jews. (Interestingly, the two views that are coldest toward Jews are extreme liberals and moderates.) On the other hand, the demographic variables do seem to make a big difference: foreign-birth, birth of foreign-born parents, race other than non-Hispanic white, and lower age all seem to increase the odds (still quite small in absolute terms) of reporting coldness toward Jews.

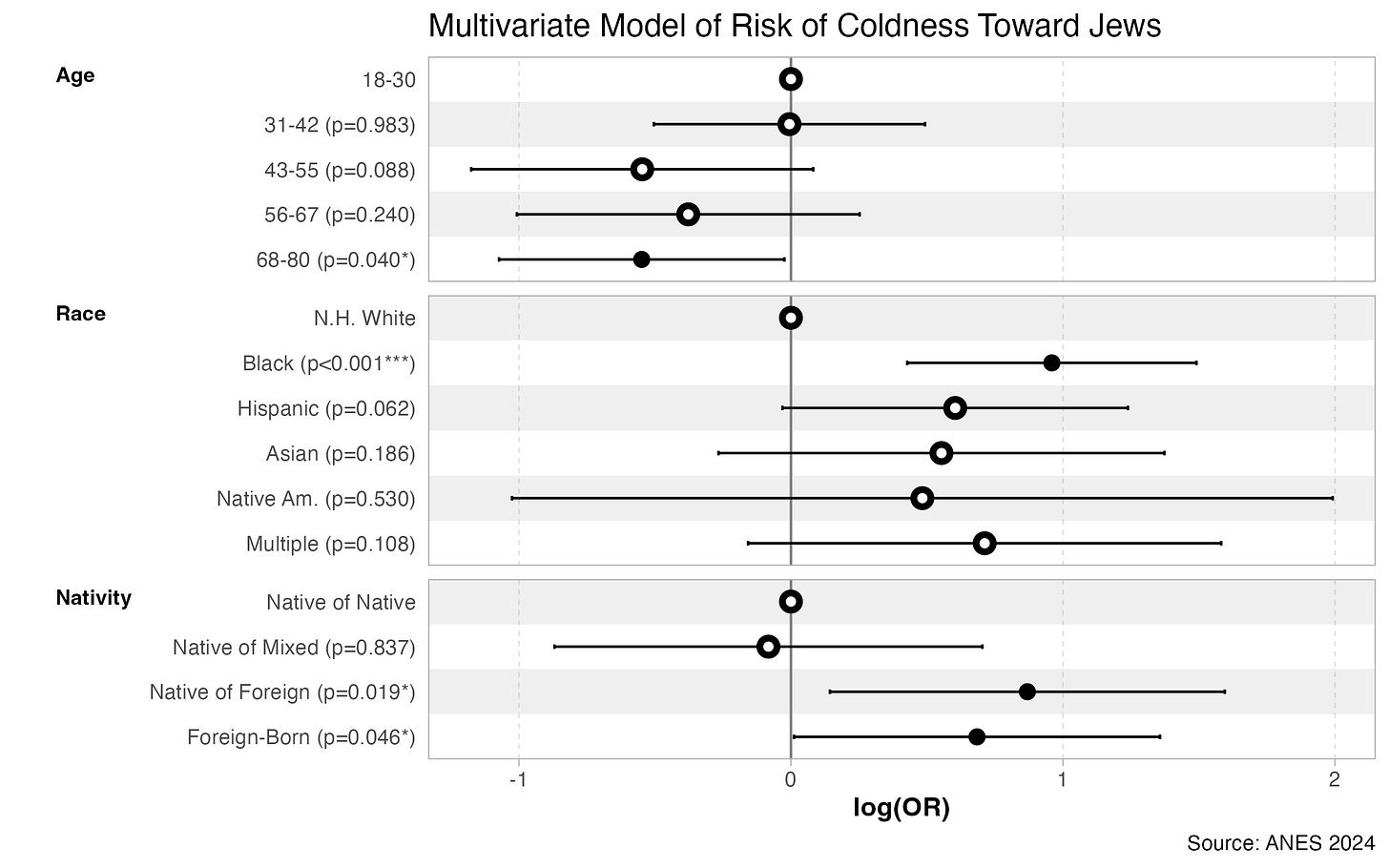

Figure 5 is a multivariate regression trying to disentangle which of the demographic factors does the driving. (Please note that it’s a logit model, not a linear probability model—the coefficients are not interpreted the same way.)5 It seems like the answer is basically a) being foreign-born or born of foreign parents or b) being black. (Also being old is protective). This is just three variables, though, so I wouldn’t quote it as gospel—e.g. there’s nothing on SES in here. But it is interesting.

In some senses, you could use all these data to corroborate a narrative increasingly common among people who spend a lot of time thinking about Jews — both those who like them and those who don’t. In this theory antisemitism (as measured by coldness) is increasingly common (almost as common as it was 50 years ago), as indicated both by these data and the sharp uptick visible online and on campuses. This effect is driven particularly by the young (and, in some tellings, recent arrivals), which means it will only get worse over time. The surveys are probably understating the true magnitude of the problem.6 The future of America is going to be antisemitic. If you like the Jews, this probably alarms you; if you don’t like the Jews, you look at these developments with glee.

I think this argument is not totally without merit. There does appear to be a change in the level of antisemitism in the ANES, directionally consistent with the change in the level of support for Israel (see start of post). And it’s not unreasonable to be worried about the former.

But I also think these data are consistent with—are arguably much more consistent with—another, simpler claim: Americans are basically fine with Jews. Why do I think this?

Explicit coldness toward Jews is and remains extremely rare. In a 1962 survey, “between 17 and 25 percent of Americans thought that Jews had too much power [and] between 28 and 38 percent of Americans would consider voting for an antisemitic candidate.” These figures were down from the Great Depression. If you fit a trend line to antisemitism over the past hundred years, it slopes straight down; a several point bump amid a major ongoing war in the Jewish state is not anything like the magnitude needed to return to the bad old days.

Extremely high warmth toward Jews remains even more common than coldness. In the 2024 ANES, about 6 percent of respondents were cold toward Jews; 21.2 percent (3.5 times as many) gave Jews a warmth score between 90 and 100.

It is possible that the recent decline in warmth is driven in part by a decline in warmth generally. If you model the relationship between my general warmth variable and warmth toward Jews in the 2024 ANES, each one point increase in general warmth increases warmth toward Jews by 0.91 points. That increasing hostility toward Jews goes with increasing hostility toward other groups is not necessarily comforting. But it suggests there may not be a unique problem.

Even if we assume the demographic variables represent some close approximation of their causal effect (and they don’t), the actual effects are small. In the bivariate nativity model, foreign birth increases probability of coldness from a baseline of 4.6 percent to 10.3 percent. In other words, you should still expect about 90 percent of foreign-born respondents to the ANES to give Jews a 50 or higher on the thermometer.

In other words, yes, there has plausibly been a level change in America’s views of Jews (not just Israel). But the level such as it is is still extremely favorable to Jews. There are, I think, two implications to this.

Implication the first: Do not expect antisemitism to be electorally popular.

I’m not going to rehearse the whole saga with Tucker Carlson, Nick Fuentes, and Kevin Roberts.7 But one interpretation of events is that there’s an ascendant coalition of Jew haters on the right who will determine the future trajectory of the GOP. Rod Dreher (not exactly known for his temperateness) has repeatedly asserted that “between 30 and 40 percent of the Zoomers who work in official Republican Washington are fans of Nick Fuentes.”

I have factual beef with Dreher’s take here. I and lots of other conservatives—people who live in America, not Hungary—think this number is made up. People routinely overestimate the size of small groups, and I suspect that when Dreher claims that 2 out of every 5 young conservative staffers are Fuentes fans, it’s because he and his interlocutors are bad at mathematic intuition.

Which is not to say, of course, that there’s no antisemitism problem on the young right. There is, quite obviously; my Twitter mentions testify as much. I don’t think I should have to tell you that I am against it, but of course I am. Separately, though, I am concerned about a dynamic in which the rest of the right convinces itself that it needs to make peace with these people, or at least tolerate them, for the sake of coalitional interests and the future of the GOP. I think, as others have argued, that this is not only morally wrong but also extremely bad politics.

And it is extremely bad politics because most Americans are fine with Jews. It is electoral poison to be on the 30 percent side of a 70/30 issue; open Jew bashing is being on the 5 percent side of a 95/5 issue. Treating these freaks with respect and insisting they need to be part of the conversation is a bad thing to do, but it is also a great way to ensure that you lose. The Democrats in many ways made this mistake with their own lunatic fringe five years ago; the object lesson there is that you shouldn’t hand power to people with ideas that most of the public hates.

This brings me to the second implication: if most people are not Jew haters, you should probably be pretty careful about whom you call a Jew hater.

When you take an introductory statistics class, and you first learn Bayes Rule, you often go through an exercise to teach intuitions about false positives. Imagine an extremely rare disease, and a test that identifies the disease correctly 90%+ of the time. If the disease is sufficiently rare, the math works out such that a substantial fraction of positives will be false—you shouldn’t actually trust your test, and should always double check.

I find this exercise useful for thinking about accusations of antisemitism, which come almost as fast and furious on X as do the weird antisemitic posts. If, in fact, only about 5 percent of the population is openly antisemitic (and that’s probably an overstatement), then a test that has even somewhat frequent false positives will often get it wrong. Or, to translate: if you accuse a lot of people of being an antisemite, and most people aren’t antisemites, then many of your accusations are going to be wrong.

Maybe this is not a big deal on its own — tests are wrong all the time, we just run them again. But, actually, accusing people of bigotry is kind of a big deal, especially when those people are not bigots! And (I will go so far as to say), a great way for Jews to increase people’s dislike for us is to spend our time accusing our friends of being our enemies. Of course, people are sometimes actual antisemites. But they are with sufficient rareness that caution is warranted in making such accusations.

That is to say: if you recognize that most Americans are fine with Jews, then you certainly shouldn’t spend time trying to make friends with the ones who aren’t. But you also shouldn’t treat people like they’re something that they’re not—that’s a great way to lose friends.

A lot of people use this figure to argue that the GOP is now actually anti-Israel. These people can’t read, and also don’t understand the age composition of the GOP population.

For this measure I use the thermometer data for gay men/lesbians, Muslims, Christians, transgender people, rural Americans, and Christian fundamentalists.

Extra credit: diagram that sentence!

I use LPM for ease of interpretation. Directions, magnitudes, and significance are all basically the same using logit.

I use logit here because it made a difference and it’s technically better for rare outcomes.

This is a favorite redoubt of those who don’t like what survey data tell them.

There’s been a bunch of coverage, you can go find it.

With regards to throwing around accusations of antisemitism, I do think calling Zohran antisemitic repeatedly is a bad idea. On the face, he appears extremely warm and charming and the accusation seems absurd to normies.

I have seen him in shows like Flagrant when he’s baited by low IQ pod bros to talk about powerful peoples obsession with calling Israel critics antisemitic, Zohran expresses sympathy with Palestinians but doesn’t take the bait and says antisemitism is a real problem and shuts them down, quite smoothly imo. Obviously this doesn’t get to what in his heart, but it is a level of responsible (if fake) public behavior the left doesn’t often practice.

Good post, as per usual.

A couple of things:

--are jews (or anyone else) accusing more people of antisemitism? which friends have been construed as the enemy? (that would certainly describe, I would think, the longer-running mission of say the ADL, which is a bad org, imo, but the recent delta doesn't sound in that vein, but maybe that's wrong)

--relatedly, my sense of the problem is distributional: it's not how much, but who. the question is whether antisemitism is rising amongst taste- and policy-makers, which (as you know) can be a leading indicator. Tucker is some random dude in his basement.

--re. 'I'm not antisemitic, I'm just anti-zionist,' I think that distinction is fraught with peril. If the majority of the world's jews are israeli, and a very strong contingent of american jews (and nearly all non-ultra orthodox practicing jews) are zionist, then as a practical matter, anti-zionism is functionally anti-(a lot) of jews. At a deeper level, it's just hard to justify anti-zionism without recourse to antisemitism (or just committed leftism/third-worldism). I know that people try, but it doesn't withstand scrutiny, and the best explanation imo is just coalitional gravitational pull...it makes sense to rationalize anti-zionism bc it makes sense to broaden party appeal to anti-zionists, i.e. arab/islamic ethnocentrism and parochialism. I think it's fair to characterize that shift as 'antisemitic' even if 'reported feelings about jews' are static. Perhaps we need a better/newer word, but 'throw the jews under the bus [unless they surrender to the supremacist demands of islamic revanchism] bc it's just politics baby' is a concerning outcome.

I'm curious if there's similar data about Europe. If Europeans hadn't changed their view of jews, and one were still to conclude that 'anti-semitism wasn't rising in Europe' then I think there's an issue with that analysis.