A few days ago, Sens. Joni Ernst and Tim Kaine published a CNN op-ed pushing new legislation to fight the fentanyl crisis. Their plan, as they explain it, is to a) “classify fentanyl trafficking as a national security threat to the US” and b) “direct the Pentagon to develop a fentanyl-specific counterdrug strategy that includes enhanced cooperation with Mexican defense officials.”

This is all well and good, I suppose. But Ernst and Kaine are not really offering a plan to control the supply of fentanyl crossing the border. They’ve made a plan to make a plan, a plan to demand that a plan ought to happen. And there’s a simple reason for that: coming up with an actual plan to control the fentanyl supply is very hard.

Drug control policy is conventionally divided into two categories: supply reduction and demand reduction.1 Demand reduction involves either discouraging use (through primary prevention) or helping people quit (through treatment). Supply reduction involves reducing the availability of the drug to the market at some level of the supply chain, from crop eradication to street-level busts. In general, supply reduction is the responsibility of law enforcement, entailing everything from international law enforcement cooperation (the DEA has offices in 69 countries) to local police operations.

Today, supply reduction is generally more controversial than demand reduction, particularly given the unpopularity of the “war on drugs.” One longstanding criticism is that supply reduction “doesn’t work”—the demand for drugs will always create a market, even and despite the state’s best efforts to suppress it. Another is that it creates all sorts of undesirable side effects, from unwarranted criminalization to violent black markets.

I am, unsurprisingly, not sympathetic to this view, for reasons that I will address at other times. But there is also another view critical of supply control, which is that the drug crisis we’re dealing with now is particularly ill-suited to a supply reduction approach. For a representative sample, take a recent essay by CMU’s Jonathan Caulkins and UMD’s Peter Reuter in Scientific American. In Caulkins and Reuter’s telling, certain features of fentanyl make it particularly resistant to supply-reduction interventions. As they write:

Fentanyl is a synthetic drug with no natural limits on its production, not a crop-based drug like cocaine or heroin. It is absurdly cheap for high-level traffickers to replace seizures. The traditional view held that international traffickers could make or buy fentanyl in Mexico for roughly $10,000 per kilogram but even if the replacement cost were $100,000—which may be more typical within US borders—then that is 10 cents per milligram, and there are typically only 2-2.5 milligrams of fentanyl in each counterfeit pill they press. Each pill might sell for $5 to $10 on the street.

The physics are as daunting as the economics. Fentanyl is extraordinarily potent (perhaps 30 to 50 times stronger by weight than the street heroin it is replacing), so the quantities smuggled are tiny compared to the U.S.-Mexican trade within which smuggling is embedded. It’s impossible to know how much illegal fentanyl is consumed in the U.S., especially given federal cuts in data collection, but our research suggests that the amount of pure fentanyl consumed in the US in 2021 was in the single digit metric tons. To put that in perspective, the U.S. imports more than 1,000,000 metric tons of avocados each year from Mexico.

Netiher Caulkins nor Reuter are advocates of drug legalization; as they emphasize, “[i]t is great mistake … to leap from pessimism about shutting off fentanyl’s supply to a conclusion that law enforcement has no vital role to play, let alone that we should abandon all drug control efforts.” But they think that efforts to control the crisis through interdiction are unlikely to work, and that law enforcement should instead focus primarily on mitigating the negative externalities of the drug trade.

I find this argument much harder to rebut than the catch-all ones conventionally offered by libertarians and their ilk. The fact that all our leaders seem to be able to do is come up with a plan to make a plan reinforces the sense that the problem may be intractable. That said, pessimism about supply reduction is not new; people like Ethan Nadelmann have been arguing it’s impossible for decades. And while I believe This Time is Different, that may just mean that supply reduction needs to look different too.

This post is an attempt at sketching approaches to supply reduction in the age of fentanyl. I outline the problem and suggest some solutions. I am not necessarily optimistic about any of them. The unified theme, though, is that the problem is much, much bigger than it has been historically. Our actions need to be proportional.

The Fentanyl Problem

In 2021—the most recent year for which we have reliable data—over 110,000 Americans died from drug overdoses. If preliminary data hold, similar figures probably obtained in 2022. These rates are almost certainly unprecedented in U.S. history. At the height of the crack crisis in the late 1980s, for example, the drug OD death rate was about 3 per 100,000 people. Today, it is 33 per 100,000. Drugs are now the thing most likely to kill Americans under the age of 50.

Most of this increase is driven by the rise of synthetic opioids, in particular fentanyl. What isn’t driven by fentanyl or its analogs is driven by methamphetamine, another synthetic drug. Heroin deaths are in decline; prescription opioid deaths have leveled off. Cocaine is a contributor, but it turns out that that’s mostly because all the cocaine has fentanyl in it now. (It’s gotten so bad that there was even an SNL sketch where the punchline is that coke has fentanyl in it.)

So the problem is “synthetic” drugs. But what does “synthetic” mean? Historically, most drugs were made from plants. Illicit opioids—opium, morphine, heroin—are refined from the sap of the opium poppy. Cocaine comes from coca. Lots of 20th century stimulants came from ephedra. Marijuana comes from … well, marijuana. (There are synthetic cannabinoids now; nasty stuff.)

Organic production is land-, labor-, and capital-intensive, particularly under the constraints of global prohibition. Those constraints are part of why many licit pharmaceutical-use drugs—opioids prescribed for pain control, amphetamines for attention, etc.—are instead synthesized from simple precursor chemicals. Big pharma has known how to synthesize fentanyl for more than 60 years, and it’s used in a variety of medical applications. If you or anyone you know have received an epidural in the process of giving birth, for example, that was probably fentanyl.

It took a long time for illicit manufacturing to catch up with big pharma. There were a few earlier outbreaks of fentanyl overdose, suggesting that individual criminal chemists solved the problem at various points.2 But until the mid-2010s, most illicit opioids in the American supply were either diverted pills or old-fashioned heroin. Over the past decade or so, however, fentanyl has more or less entirely replaced these. It’s also leaked into other drugs, which is why most cocaine overdose deaths now also involve fentanyl, and fentanyl and benzodiazepine deaths are a major problem.

Why has the rise of fentanyl translated into an increase in deaths? Fentanyl is much, much more potent than the opioids it’s replaced. In particular the distance between its effective dose and over-dose is much smaller, meaning that it’s much easier to overdose on. Given that it’s killing their clients, why have illicit manufacturers substituted so aggressively to fentanyl? The simple answer is efficiency. Fentanyl, and synthetic drugs more generally (methamphetamine, but also many of the “new psychoactive substances”) are an industry-altering innovation for the illegal drug business, as much as or more so than they were for the legal one.

Caulkins and Reuter explain why, but to briefly retread: synthetics are far less capital- and labor-intensive than organics. Replace hundreds of hectares of land with a single lab and some simple precursor chemicals purchased online; replace dozens of fieldworkers with a single or a few chemists. Equivalent yield comes from exponentially less labor, or vice-versa.

In addition, synthetics are arbitrarily powerful. Fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin, but carfentanil, usually used as an elephant tranquilizer, is 100 times stronger than that. That means the potency of your product is not subject to the whims of nature. More importantly, it means much smaller volumes are needed to supply the same level of demand. As Caulkins and Reuter write, this makes smuggling much easier. It also makes point-of-production supply control much harder: you can crop-dust poppy fields from the air, but you can’t do the same thing to a lab in someone’s house, especially not when that house is in Mexico.

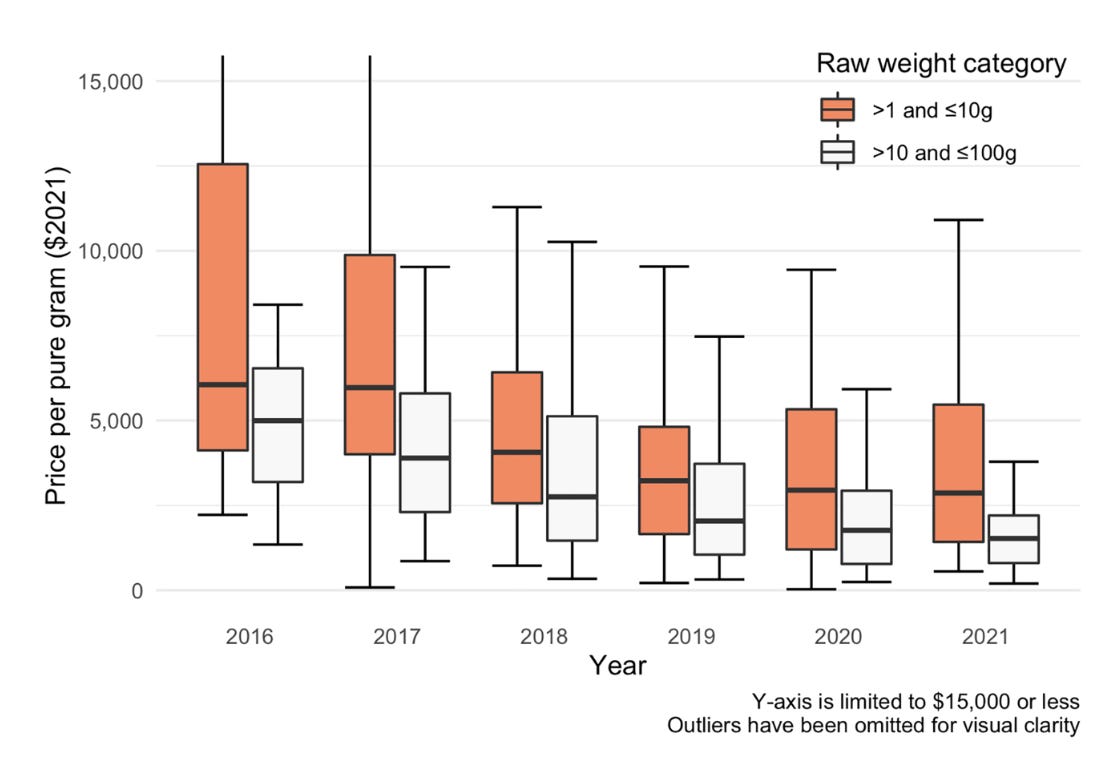

Synthetics are way easier and cheaper to produce. As that knowledge propagates, we should expect the market to grow more efficient, as more producers enter into it and drive the price down to production cost. And indeed, the price of synthetic drugs has plummeted. Fentanyl’s price probably fell 50 percent between 2016 and 2021. Between 2016 and 2022, InsightCrime found, the wholesale price of meth dropped from $17,000/kilogram to $3,500/kilo, an 80 percent decline. Caulkins and Reuter estimate that a fentanyl pill runs $5 to $10 on the street, but I think they’re out of date—on my recent visit to Portland I found out that you can buy a pill for $2. (And that’s on the west coast, where fentanyl has been slower to show up!)

What you’re seeing in the illicit drug market, in other words, is the crushing capitalist logic of innovation. A new technology has displaced the old way of doing things, creating massive new efficiencies and cratering prices. This is the genesis of our drug crisis—a transformation in the way that illicit drugs are made and sold.

Price Control

Wait, wasn’t this supposed to be an essay about supply control? Well, yes. But to understand the problem facing supply reduction operations, you have to understand how they work.

One silly argument deployed by opponents of prohibition is that you can’t get rid of drugs—supply control will never fully exterminate the market. This isn’t, strictly speaking, true, at least not at a per-substance level. Internationally coordinated efforts effectively removed Quaaludes from the illicit drug supply in the 1980s; a few well-timed seizures shut off the flow of heroin to Australia for an extended period of time in the early 2000s; well-timed lab shutdowns crushed early fentanyl outbreaks and created an “LSD drought.” Prohibition sometimes makes markets monopolistic, and if you can shut down the monopolist, you can take out the market, at least for a while.

But mostly, supply control works by making it harder to get drugs. By seizing drugs or arresting drug dealers, you can reduce the supply, increasing the price. Demand for drugs is not perfectly inelastic; if the price goes up, consumption will go down, both on the extensive and intensive margins. You also make acquisition more effortful by increasing search time for would-be buyers—the less available the drug is, the longer people have to spend looking for it, the less they use and the more they have to pay to use.

One of the interesting corollaries of this model is that targeting the drug supply at its point of origin will have a limited impact, because most of the final price comes in mark-up along the supply chain. Reuter and Mark Kleiman, in their seminal paper on the topic, offer an illustrative example: “the ten kilograms of opium in Thailand needed to make one kilogram of heroin cost at most $1,000. If that price fell to $100 or rose to $5,000, it would have little effect on the price of heroin delivered to the United States (roughly $200,000 per kilogram at the importation level).” The increase in price between nodes on the supply chain, in other words, is big enough to swamp the downstream effect of any increase in price at the earliest nodes.

If you’re trying to dry up the fentanyl supply all together you want to target choke-points early in the supply chain (more on that in the next two sections). But if you want to limit consumption via price, you want to go after it on the retail level, increasing both cost and search time. Is increasing the intensity of street-level enforcement a viable strategy for controlling the fentanyl supply?

Well, how intense is enforcement currently? In 2021, police agencies reported about 560,000 drug arrests to the FBI. That’s a fairly large number, but it’s also a precipitous decrease versus 2019, when the official figure was 1.1 million. The chart above (data and details in the footnote) captures the longer-run trend, reporting relative levels of non-marijuana drug arrests in departments which report in all the years considered.3

One the one hand, the data confirm that the two most recent years have seen a dramatic departure from the recent trend. COVID and Floyd-related protests and policy changes led to a dramatic reduction in “low-level” drug-related arrests. In recent years, then, we are operating well below where we historically have. At the very least, restoring enforcement activity to prior levels should have some effect.

On the other hand, OD deaths were already skyrocketing in 2019. Doing a million-plus drug-related arrests a year was clearly only doing so much to the fentanyl supply. Fentanyl is so much cheaper, and easier to smuggle, that it almost certainly reduces the coefficient of enforcement’s effect on supply and price. Applying the same level of enforcement in 2019, when the market is saturated with fentanyl, should have less of an effect on consumption than in 2009, when it wasn’t. Consequently, if we want street enforcement to be effective, we have to dramatically increase its extent and intensity just to get back to where we were before fentanyl.

This is, of course, not a politically popular proposal. And I have mixed feelings about it myself. There’s a fixed supply of policing, and the more man-hours spent on drug enforcement, the fewer spent on controlling e.g. the violent crime problem. Arresting way more drug users in the absence of substantially more treatment availability also seems neither efficacious nor just. Yet treatment and enforcement also compete for limited public dollars. That said, the costs of under-enforcing are substantial, involving not just public order disrupted or addiction entered into, but lives lost. Fentanyl is much more deadly; drug enforcement should rise proportionally as a priority, even if it still does not beat out other drug and non-drug policy priorities.

So I’ll stop short of endorsing a massive increase in street-level enforcement, while observing that it may be one approach to tackling the crisis. One compromise might be to scale up an intervention which is itself inspired by the Kleiman/Reuter “Risk and Prices” approach. So-called “drug market operations” or “interventions” entail simultaneous arrest and prosecution of the major drug dealers serving a targeted drug market. Though the evidence base is mixed, in some cases they dramatically reduce both drug using and violence in the targeted areas even after the end of the intervention. Given finite resources, targeting the most problematic areas may give the largest return on investment.

Shutter the Factories

Let’s assume that—for practical, political, or moral reasons—a huge increase in street-level drug war isn’t going to happen. What else can we do? Go after other points in the supply chain, of course.

As this recent InsightCrime report details, the fentanyl supply chain works something like this: fentanyl precursors (and increasingly “pre-precursors,” substances that can be turned into now-controlled pre-cursors) are manufactured in China, often by firms that also manufacture pharmaceutical ingredients for the licit supply chain. They’re then sold to Mexican intermediaries, who pass them on to cooks that produce the final product. From there the drugs are smuggled over the border, usually by one of the two big cartels, to final distributors in the United States.

Why do the precursors come from China? Because China is the world’s largest producer of pharmaceutical ingredients. The growth of its chemical industry has outpaced every other nation’s. As a result, China is a go-to source for precursors and pharmaceutical ingredients for the licit pharmaceutical industry. The illicit industry is arguably just a sideshow to the main event: Americans spent maybe $150B on illicit drugs in 2016, compared to between $300B and $500B on licit prescriptions, depending on your source.

For reasons discussed in the previous section, we should be skeptical of “source country” control efforts, except where they plausibly cut off supply of a substance altogether. But there are several reasons to think that Chinese precursor producers offer an opportunity for such a decapitation, at least temporarily.

One is that there are relatively few of them: InsightCrime estimates that there are at most 500, and probably fewer, because many companies distinct on paper are probably part of the same business/family networks. Another is that these firms are one of the few places the fentanyl supply chain touches the licit market. This differentiates the illicit synthetic market from its organic twin, insofar as the latter usually starts with illicitly grown plants. It means that they have to, at least nominally, conform to the demands of regulators in a way that illegal operators don’t. But it also means that a key part of the fentanyl supply chain is exposed to licit market pressures—if forced to choose, on average they should pick the bigger licit market over the smaller illicit one.

In a recent Foreign Affairs essay, Brookings international crime scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown proposes that the United States team up with other countries which have been downstream of China’s under-regulated pharmaceutical market to pressure the Chinese to live up to their tough-on-drugs image:

Among the best practices the United States and others should push for are self-regulation systems to detect and police suspicious activities and “know your customers” policies. It should continue demanding that China take down websites that illegally sell synthetic opioids to Americans or to Mexican criminal groups. And it should encourage China to adopt more robust anti-money-laundering standards in its banking and financial systems and trading practices. Washington can underpin such requests with the threat of sanctions. Punitive measures could include cutting off non-compliant Chinese firms from the U.S. market and targeting prominent pharmaceutical and chemical industry officials. U.S. law enforcement, meanwhile, should indict as many Chinese traffickers and their companies as possible.

These are, I think, good first steps. But they are not proportional to the scale of the problem. If minimizing loss of American life is the number one priority of American diplomatic relations with China—not an unreasonable assumption—then controlling the outflow of precursors from China has to be fairly high up on the list of goals. Somewhere below “preventing nuclear exchange,” but not that much below.

This is particularly so because controlling its own chemical industry is something the Chinese claim to be and have proven able to do. Finished fentanyl used to be made in China, rather than Mexico, but that changed after the Chinese government cracked down on production. Controlling black market actors is, by definition, hard for the state to do. But controlling gray market firms is relatively easier, because they have to at least appear to comply with regulation. Such control thus needs to be a top priority for relations with China.

One additional step American regulators could take is to control precursor producers by contrlling American pharmaceutical firms. They could prohibit American drug makers from buying active ingredients from foreign companies unless they have been specifically authorized to do so, and specifically if the foreign manufacturer has proved to an American regulator that they are not also trafficking in illicit fentanyl precursors. Such a “presumption of guilt” regime would incentivize some precursor producers with a foot in both markets to prioritize the larger licit market over the smaller illicit one. (It would also drive up drug prices in America, a significant but plausibly acceptable cost.)

A reasonable objection is that a crack-down on Chinese precursor manufacturers will just cause illicit fentanyl manufacturers to shift sources. That could be to a different under-regulated market—India is the most likely candidate, but South Africa, Nigeria, and Indonesia are also options. Or it could mean in-sourcing even initial chemical production to Mexico. This is the “whack-a-mole” argument against supply control—knock down one source, no matter how big, and another one will just pop up to fill its place.

I think this is right, to some extent. But until the synthetics trade is fully vertically integrated, the need for precursor manufacturers to interact with the licit market and the regulators thereof will always be a powerful leverage point for reducing supply and increasing price. The same approach in theory should work in India as works in China. And if the cartels move even initial chemical production into the illicit market, they’ll lose out on the efficiencies that come with piggy-banking off of grey market operators’ scale, reducing their already razor-thin profit margins.

Close the Border

There’s another possible choke-point in the fentanyl supply chain: the Mexican border.

America is, it turns out, basically the only developed country with a fentanyl problem.4 You can come up with all sorts of high-sounding explanations, but the actual reason is simple: The U.S. gets most of its drugs from Mexico, whereas most other developed nations get their drugs from southeast Asia. The Mexican traffickers have switched to fentanyl, while the Asian ones haven’t.

This market segmentation is in large part because America has an open border with a de facto narco state. When I say “open border,” I mean that as a result of NAFTA/USMCA, literally millions of trucks cross the border every year. This free flow of goods is great, except that it also facilitates smuggling. When I say “de facto narco state,” I mean that the cartels exercise sovereignty over large swathes of the country. Mexico is in a continuous state of war with and between the cartels. The country saw more than 30,000 homicides in 2021, most of them linked to cartel violence. So we can’t really rely on the Mexicans to ensure that the stuff they’re letting across our border isn’t deadly poison.

I think Caulkins and Reuter are probably right that the problem of interdicting fentanyl at the border will not yield to half-measures. Because of its high potency per dose, total fentanyl consumption in the U.S. is maybe 5 tons per annum; total Mexican avocado consumption, the two note, is on the order of a million tons. Interdiction involves looking for a needle in a haystack, except that every time you miss the needle, lots of people die. I’ve heard pitches about special scanning tech, but I just don’t buy it—the physics are, as Caulkins and Reuter say, daunting.

But it’s worth asking: if our current trade arrangement with Mexico is also the proximate cause of the drug crisis, is our current trade arrangement actually conducive to the national interest? Felbab-Brown has some useful numbers:

The economic cost of the opioid epidemic—to leave aside its immeasurable human toll—is simply too enormous to countenance inaction. In 2020, estimates put that cost at nearly $1.5 trillion. In contrast, in 2019, U.S. goods and services trade with Mexico totaled only $677.3 billion, with imports from Mexico at $387.8 billion.

The source for Felbab-Brown’s $1.5 trillion figure is, I think, this JEC report. But that’s just the cost of the opioid epidemic, counting e.g. only 81,000 deaths towards its total. In 2021, the figure is 111,000, and most of these are also the fault of the Mexican cartel. If you take the value of a statistical life as $11 million,5 then we should tack another $300 billion on to the figure. And that's without estimating non-mortality costs! And only including the costs of currently existing treatment, rather than optimal treatment (which is way more than we currently provide). The drug crisis in general—the synthetics crisis—almost certainly costs, in dollars and lives, at least $2 trillion annually.

Felbab-Brown’s view is that we need to “intensify border inspections, even at the risk of substantially slowing down the legal trade and causing serious problems for perishable Mexican agricultural exports.” Again, I think this is a half-measure. The volume of U.S. trade with Mexico, substantial that it is, is dwarfed by the costs associated with the cartels’ unfettered access to our market. The U.S.’s default negotiating position needs to become that we are going to seal the border with Mexico, at points of entry and in between, until the Mexican government can actually control the territory it nominally rules.

The costs of this would be, of course, enormous. It would have significant effects on prices and wages, in the U.S. and Mexico. But against those costs must be set the truly prodigious costs of a hundred thousand deaths a year, never mind the costs of everything that leads up to those deaths. If you take that number seriously, you have to be willing to take drastic action.

Is it Worth It?

If you want to have an impact proportional to the fentanyl problem, you have to be willing to take proportional action. A million drug arrests a year might be an order of magnitude too low. You probably can’t reduce trade with Mexico by 10 percent; you probably have to reduce it 90 percent or more. There are real constraints on making these choices—a 10x increase in the number of drug arrests under constant police manpower means a big decrease in other enforcement priorities. Ending trade with Mexico would have huge economic costs. There are also political constraints: even if I don’t think the economic benefits are worth it to have an open border with a narco-state, lots of people do, and many more are allergic to the kind of radical change closing the border would entail.

Because of these constraints, I am skeptical that more enforcement is the best use of the marginal drug policy dollar. All else equal, we may be better off directing money towards massive investments in demand reduction, rather than supply.6 There are huge gaps in our treatment infrastructure, and we know almost nothing about how to do primary prevention. There is, I suspect, more room for improvement per dollar spent—and therefore more capacity for proportional response—in those areas than there is in supply reduction.

That said, in the current crisis, any estimation of policy pros and cons must take into account the enormous scale of the issue. 100,000 deaths a year is an unprecedented emergency. And even if supply-reduction alone can’t solve the problem, even if demand reduction is the better angle, there are still supply-side steps we can take. We can restore drug enforcement to pre-2020 levels. We can make precursor control one of our top priorities in negotiating with the Chinese. And we can at the very least dramatically curtail trade with Mexico, to make interdiction easier. These steps have to be taken at a dramatic scale. But the problem is dramatic, so too must be the solution.

There’s also harm reduction, which tries to reduce the negative effects of drug use without necessarily reducing either demand or supply. But that’s a different can of worms.

A similar pattern obtains with methamphetamine. If you zoom in on the meth death trend, there are two waves. The first one, which peaks around 2005, involves small U.S. based meth producers synthesizing meth from over-the-counter ephedrine drugs. (This is Walter White’s meth crisis.) Then Congress passes the CMEA, domestic meth lab busts peak, and the problem subsides … until Mexican cartels get into the meth game on an industrial scale.

The data are Jacob Kaplan’s cleaned version of the FBI’s arrests data, available at ICPSR. I drop marijuana arrests because they’re noisy vis-a-vis actual drug enforcement levels, versus pretext enforcement. But the patterns are similar with them included. I use only constantly reporting agencies to avoid the skew created by agencies dropping in and out of reporting. I report percentage-wise because this restriction means the absolute level is not that meaningful.

I mean, Estonia has a fentanyl problem, for extremely interesting reasons largely orthogonal to this piece. But we’re way ahead of everyone else.

The EPA calls it $7.4M in 2006 dollars, which is a bit more than $11 million in 2023 dollars. Inflation!

I’ll have an essay in National Affairs in the next couple of months talking through this agenda, but in short it looks like a) dramatically expanding the availability and use of treatment, especially compulsory treatment and b) dramatically expanding primary prevention efforts.