The Police Unions Puzzle

Evidence-based ambivalence and "one weird trick" for policy

It is in vogue, my colleague Dan DiSalvo noted in a 2020 National Affairs essay, not to like police unions. They were one of the components of policing “under a microscope,” in DiSalvo’s words, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder (just like basically everything else about policing). But before, and still today, it was not uncommon to depict police unions as a malign force bearing a substantial portion of the blame for high-salience police killings.

The argument goes something like this: police unions, like any other union, are meant to protect their members. Sometimes that means protecting them from bad bosses. But it can also mean (ostensibly) interceding to protect against misconduct investigations. When cops do something bad, civilian government, NGOs, and the public will try to hold them accountable, and the unions will try to stop that from happening. They will also prophylactically protect cops by advocating for politicians who oppose accountability and, most importantly, writing provisions into their contracts which could impede accountability.

The solution, of course, is to break, or at least dramatically reduce the power of, the unions. Doing so is not merely a way to reduce police misconduct; it is, Adam Serwer asserted in the Atlantic, a necessary predicate of any other reform:

Reining in police unions may not seem like the most urgent response to this crisis. But no reform effort can hope to succeed given their power today. As long as they exist in anything like their current form, police unions will condition their members to see themselves as soldiers at war with the public they are meant to serve, and above the laws they are meant to enforce.

I am, I will freely admit, pretty skeptical of most institutional critiques of policing—arguments which suggests that police misconduct is not the work of bad actors who somehow got the job, but a predictable byproduct of some institutional feature. But I am also, by ideological disposition, at least supposed to be suspicious of public sector unions.1 If teachers’ unions tend to prioritize their members’ paychecks and ideological preferences over the well-being of kids—and I tend to think they do—it makes sense to similarly see police unions as prioritizing their members’ safety over the well-being of the people they might kill. If there’s a room for bipartisanship on this issue, indeed, it may be on police unionization: liberals don’t like police, conservatives don’t like unions. It’s a perfect match!

Here’s what holds me back: the actual evidence on the average effect of police unions on misconduct is pretty mixed. The most persuasive research, in fact, suggests that police unions have no measurable average effect on police misconduct. And there’s a host of supplementary research that suggests police unions provide indirect benefits, not just to their employees, but to the public in general.

There’s a lesson here—about optimal policing policy, sure, but also about policy solutions in general. Breaking police unions is one of the many “one weird trick”s floated to dramatically reduce officer involved shootings. Such tricks tend to pop up around high-salience policy issues. But in my experience—and certainly in the case of union-busting—they promise far more than they deliver. Perhaps we should be skeptical of such solutions in the first place.

That Literature I was Talking About

How would we estimate the effect of police unionization on misconduct? In my last post I talked about difference-in-difference analyses. If you have multiple units observed at multiple times (i.e. panel data), and some of those units undergo treatment throughout the observation period, you can observe how treated and untreated units compare, before and after treatment, controlling for everything else about period and unit. And in theory, you should be able to do this with police unions. Build a data set of when unionization happened in different locales, count police killings in those same locales, and feed your panel data into the TWFE machine. Simple, right?

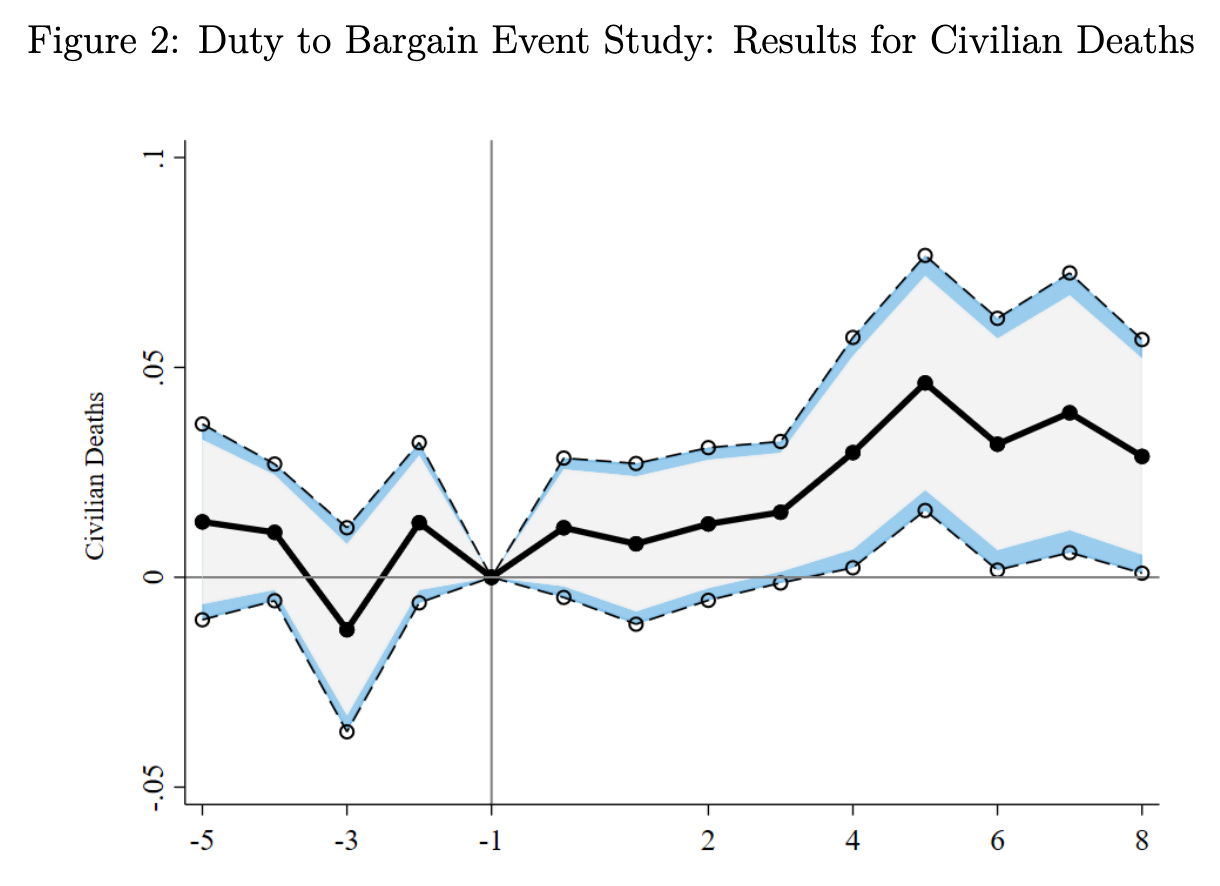

And indeed, Cunningham, Gillezeau, and Feir 2021 (hereinafter just Cunningham et al.) set out to do that. They construct panel data of counties in states that did and did not adopt a “duty to bargain”2 with police unions in the period 1959 to 1988. (They also use geographically contiguous counties in treated and untreated states as a separate treatment/control approach.) They control for both county-level fixed effects and year fixed effects.3 What do they find? Becoming a duty-to-bargain state causes a statistically significant increase in civilian deaths. Cunningham et al. suggest that the increase is concentrated among non-white civilians, and contend that duty to bargain explains about 10 percent of non-white civilian deaths at the hands of police in the period of interest.

So that’s settled, right? Well, not quite. Methodologically, Cunningham et al. are on the straight and narrow. But let’s talk about the data.

To construct their independent variable, “civilian deaths caused by law enforcement,” Cunningham et al. use the 1959 to 1988 Vital Statistics Multiple Cause of Death Files, counting county and race level “deaths by law enforcement intervention, excluding deaths due to legal execution.” These data are the oldest source of information about police killings we have. But they’re also widely considered to be extremely unreliable. Criminologist Frank Zimring explains:

For many years, the number of killings by police was substantially underreported simply because county coroners didn’t identify many killings that were caused by police, and thus while the report of a death went into the system, it was not listed in the legal intervention category. The likely cause of the problem is innocent oversight, because, as I’ve observed, police killings are a tiny category in total deahts (less than one-tenth of 1 percent), and these cases have never been regarded as an extremely important aspect of Vital Statistics reports.4

Coroners just didn’t bother to keep track of these statistics! This, along with similar under-reporting problems in the FBI and Bureau of Justice Statistics data sets, is part of why crowdsourced databases of police killings—Fatal Encounters, Mapping Police Violence, the Washington Post shooting database—now exist. Everyone agreed the official sources are just too unreliable. If coroners’ non-bothering was time-invariant, Cunningham et al. contend, then it should be absorbed by the county fixed effects. But I don’t buy that it is: coroners will change practices over time, and coroners themselves will change over time, in unmeasured ways.

My concern here, in other words, is “garbage in, garbage out.” Yes, when you do this estimate with the data available, you get a large effect for police killing of non-white people. But the data are unreliable, so that could just be noise—a problem you can’t make go away with fancy methods.

Okay, fine, what about Dharmpala, McAdams, and Rapaport 2019 (hereinafter just Dharmpala et al.)? It’s a clever little study. Basically: in its 2003 Williams decision, the Florida Supreme Court granted county sheriffs’ deputies the right to organize and collectively bargain. Dharmpala et al. compile data on incidents of misconduct and disciplinary actions against officers, covering 1996 and 2015. To end up in the database Dharmpala et al. use, the complaints have to be sustained at least once, so we know they aren't just people harassing the cops. And we don't have any reason to believe they have the same non-reporting problem as in the Cunningham et al. data.

Using these data, Dharmpala et al. test the effect of Williams on complaints against sheriffs’ offices, using police departments (which are already treated) as the control group. They construct a model that includes agency and year fixed effects, as well as a variety of covariates. Good stuff! Here’s how they summarize their results:

Our estimates imply that the right to bargain collectively led to about a 40% increase in violent incidents at SOs [(i.e. Sheriff’s Offices)], which appears to persist over time. While this effect may seem strikingly large, the baseline rate of violent incidents is low. The estimated effect implies an increase of 0.2 violent incidents per agency-year, relative to a pre-Williams mean among SOs of about 0.5. At a typical SO with 210 officers, this effect corresponds to one officer being involved in one additional violent incident every five years. So described, the estimated effect is not implausibly large, though it points nonetheless to a substantial divergence between SOs and PDs following Williams.

I would describe this as pretty credible: relative to untreated PDs, having access to unionization as an option increases the risk of SOs committing violent misconduct by a large percentage, although that is in part because the underlying rate is low. It’s not the 10% of all non-white deaths, but it’s a real effect!

Okay, let’s talk about Goncalves 2021.

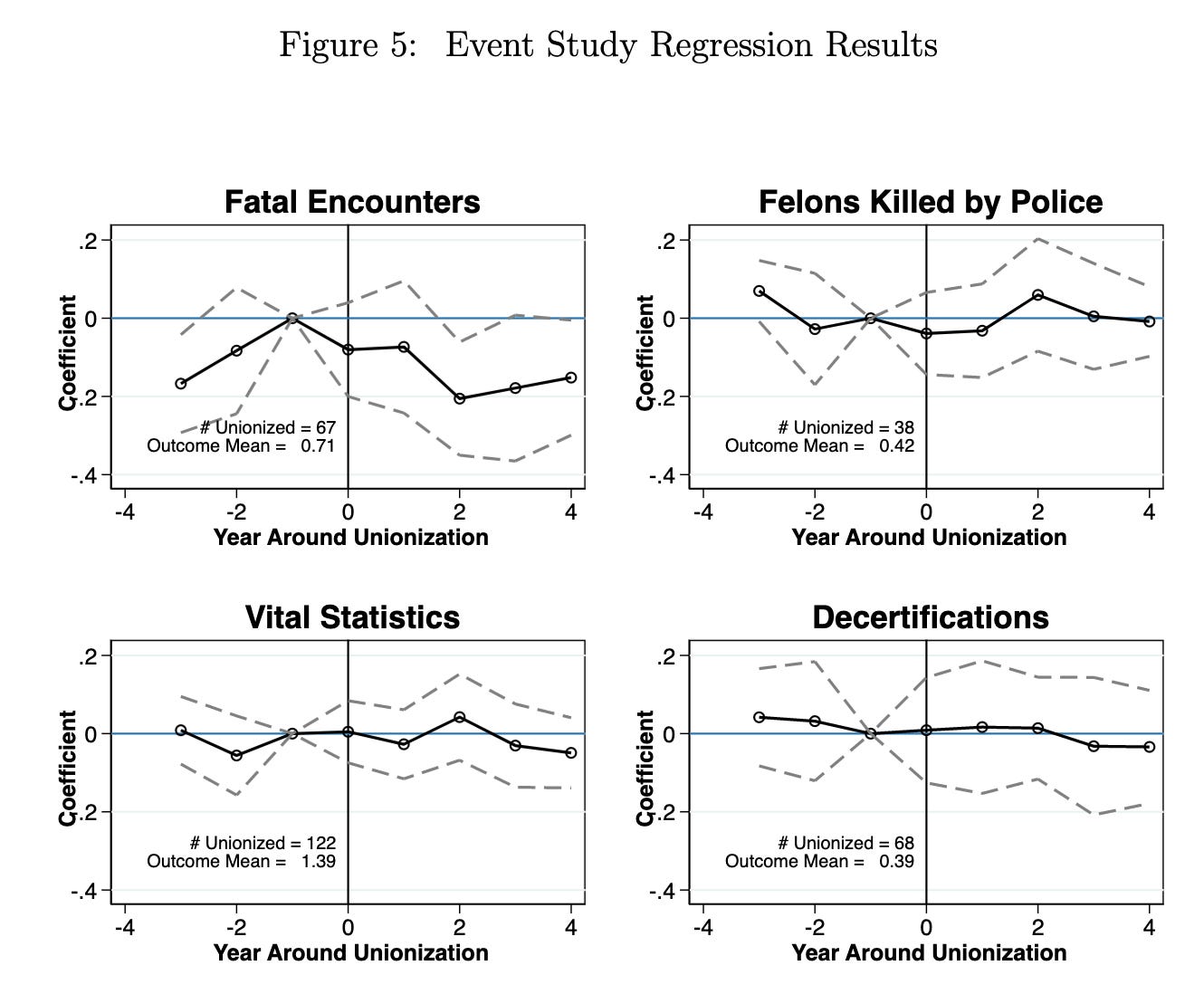

Goncalves reports the results of two different difference-in-difference analyses. One is sort of like Cunningham et al., in that it’s national. But instead of using “duty to bargain” laws, it uses federal survey data on most police departments to track which departments are actually unionized, and estimates unionization’s effect on police killings, as measured by the aforementioned NVSS data, FBI data, and the Fatal Encounters dataset (obviating concerns about using bad data). It also measures unionization’s effect on decertification in 26 states from which Goncalves obtained detailed public records. The second analysis uses a hand-compiled data set of Florida unionization votes, comparing police departments that voted to unionize with those that didn’t, and the ensuing effect on state license revocations.

In some senses, Goncalves is a combination of Cunningham et al. and Dharmpala et al. Like Cunningham et al., it looks at the effect of rolling changes in unionization at a national level on police killings (with more reliable data than Cunningham, but similarly critiquable); like Dharmpala et al., it looks at how unionization in Florida affects misconduct as measured (more reliably) by state agencies. There’s one key difference, though: “While these studies focus on the right to unionize,” Goncalves writes, “my study estimates the impact of unionization in a time period when most officers have the right to unionize.”

And the results are mostly nulls? As Goncalves summarizes it, “I find impacts that are small and statistically insignificant, and most specifications rule out more than a 10% positive impact. … While the evidence does suggest that unions reduce civilian oversight and increase legal protection for officers, these impacts do not translate into elevated misconduct.”

This is not exactly a narrative-supporting finding. The Annual Review of Criminology, in its summary of the research on the relationship between police unions and misconduct, awkwardly shoves it into a concluding paragraph of the relevant subsection. ("Among the extant quasi-experimental research, [of which there are three examples]5, Goncalves (2021) is the lone study [again, among three studies] that does not find evidence of significant increases in police violence following police unionization. However, in contrast to the other studies described in this section [which are the two previously reviewed], it is important to note that the Goncalves study looks at unionism in general, not collective bargaining specifically[, and this makes it less relevant for some reason].")

But when I weigh this evidence out, I kind of lean towards the Goncalves view of things. Cunningham et al. has a GIGO problem. Dharmpala finds an effect for sheriffs’ unions specifically in Florida, specifically versus PDs—how externally valid is that?6 And both are sort of "intent to treat" analyses—they look at jurisdictions that adopt some policy change conducive to unionization, rather than measuring actual unionization as such. Goncalves, by contrast, looks at the effects of actually existing unioniozation—a sort of "treatment on the treated" analysis—and comes up with a lot of big fat nulls. It's just one study, sure. But the whole field has only a few studies, and it seems the most persuasive.

Unions Can Have More Than One Effect!

So what to make of these findings? How do we square the Goncalves estimates with the (plausible!) theoretical model propounded by critics of unions?

Earlier I presented one standard story about police unionization: police unions protect their members by increasing the costs of discipline, reducing accountability and thereby increasing misconduct. Another story, though, is Becker and Stigler (1974)'s.7 In this version, unionization increases wages, which in turn increases the opportunity cost of misconduct.

These are both stories about what unionization does to officers: protects them against consequences, but also incentivizes them to behave better. One channel for this latter effect is pay, but it’s not the only one. Unions are institutional actors, and while they have an imperative to protect their members, doing that also means doing things to protect their political standing. If police misconduct implicates the political legitimacy of unions—as, I think, is a premise of this essay—then unions have some vested interested in controlling police misconduct, not just protecting against it.

And indeed, there’s some evidence that they do that!

Rivera and Ba 2019 investigate the effects of oversight of the police (namely the Chicago PD) on misconduct. Specifically, they examine the effect of a) public oversight in the wake of the death of Laquan McDonald and b) memos from the police union to line officers about the need to avoid complaints, published in the union newsletter. While misconduct complaints increased following the McDonald scandal, they fell in the wake of the union memos—suggesting union self-regulation reduces misconduct as well as if not better than public criticism.

Chandrasekher 2013 studies the NYPD, exploiting the fact that different ranks of police officer are "out of contract" (i.e. their contract has expired and they don't have a new one yet, meaning they work under old and less-favorable terms) at different times. It finds that police misconduct increases with time spent out of contract. Conversely, that suggests that regular union bargaining reduces police misconduct, if even just by the Becker and Stigler channel of keeping their wages growing.

Chandrasekher 2016 (same author as above) studies the 1997 NYPD police work slowdown, which was a pressure campaign to secure a new union contract. It finds that while the NYPD dramatically reduced its ticket writing, it did not reduce arrests or other forms of criminal enforcement—a strategic choice which may have been motivated by the union’s desire to garner public support for its agenda. In other words, the union guided its members behavior to curry favor with the public, suggesting a strategic political actor aware of the importance of public perception.

There are other plausible channels here. For example, working longer shifts or back-to-back shifts dramatically increases the odds of a complaint against a cop; unions can work to reduce this burden. Morabito 2014 presents cross-sectional but interesting evidence that police unions drove the adoption of Community-Oriented Policing, which may in turn improve police community legitimacy.

Returning to Goncalves: One way to explain null results is that the treatment had no effect on the outcome. Another way to explain null results is that the treatment had multiple, competing effects on the outcome. Maybe police unions cover for officers when they do bad things. But they also create environments in which officers are less likely to do bad things, because they are better paid, work shorter hours, etc. And they have incentives to pressure officers not to do bad things in the first place, because aforesaid coverage costs the union—in time, in money, and in political legitimacy.

This suggests that public perceptions of the effects of police unions are contaminated by survivorship bias. We see the high-salience instances of misconduct that do happen, and that unions protect their members in those situations. We don’t see the instances of misconduct that don’t happen because of police unions, even though that effect is there too. The result is a net non-effect, even and in spite of the high-salience instances of failure.

Job Protections as a Bargaining Chip

One plausible response to this model of police unions is to ask if we can mitigate the harmful channels while preserving the beneficial ones. Can unions improve working conditions (and thereby reduce abuse) without also affording more protection for misconduct?

That’s a question big enough to merit its own investigation. But I want to suggest, just in brief, that we should be skeptical about the real-world tractability of such a “trade-off” approach, in which police unions get something and in return remove protections from the package of benefits they negotiate for their members.

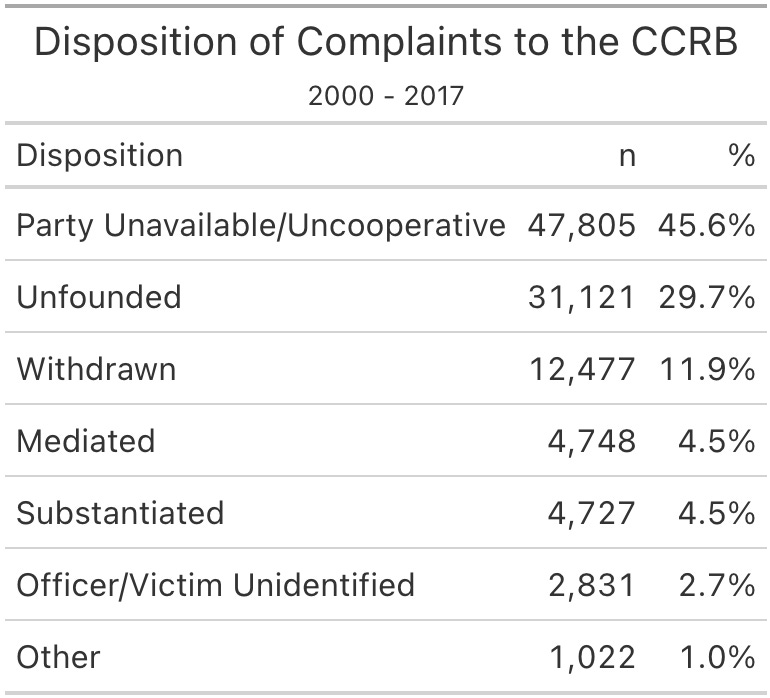

Protections from unfair discipline are a fairly big deal for cops.8 The table above, for example, captures the disposition of over 100,000 complaints filed with the NYPD Civilian Complaint Review Board, the independent oversight body which, well, reviews complaints. Of those, fewer than 5 percent were labeled as substantiated—about as many as lead to mediation, and half as many as were just withdrawn. 30 percent were ruled unfounded. In the plurality of the cases, one of the relevant parties—the complainant, the alleged victim, or a witness—just doesn’t show up or doesn’t cooperate. (This is not exactly a sign of a sterling case.)

In other words, most complaints against the cops weren’t substantiated. There’s a pretty high risk of false positives in complaints against police!

So it's not crazy for cops to want protections, even as those protections necessarily increase the risk of true positives going unaddressed. If you want to whittle away these protections, you need to offer an increase in some other component of compensation.9 You can offer them nicer working conditions, but you get diminishing marginal returns in these pretty quickly—you can't reduce working hours below 0 (and really not much below 8), and there's only so much dental insurance you can offer me to make up for the fact that people frequently will make stuff up about me.

The other thing you can bargain with is, well, money. People like money, and while there are diminishing marginal returns in dollars, doubling someone’s pay still has a bigger effect than doubling their dental insurance. So can we pay cops more to ratchet back some of the protections? I think the answer is probably no, at least not under current conditions.

To make a long story short: There’s a really tight market in police labor right now. A wave of retirement, fiscal tightening since the Great Recession, a culture of hostility towards police, and rising opportunity costs in other sectors, have all led to declining police staffing ratios, unlikely to rebound for years. Agencies have responded by boosting salaries, hiring bonuses, and retention bonuses. But there’s an arms race dynamic to this, particularly because hiring bonuses can rise to the level of the cost of training a new officer, as much as $100K. Exacerbating the problem is that much new hiring consists of “lateral transfers,” bidding up the total cost of employment. There are 18,000 police employers in the United States, most of them fiscally constrained small localities. Add to this the aforementioned state of police labor supply, and you get a seller’s market.

In the current environment, in other words, budget-conscious localities are already paying out the nose for police salaries. Paying more to reduce protections is an incredibly expensive proposition. You can get around this with added federal funding—COPS spending is distressingly low, as I’ve argued at length elsewhere—but that only gets you so far. Indeed, against this backdrop, it’s easy to see why unions extract so many employment protections for their members: they’re much cheaper for employers, in budget terms, than actually paying more is!

I think there are half-measures worth investigating here. There’s still a lot we just don’t know about which employment protections contribute to misconduct, and which ones don’t—better research could help selectively target the most problematic terms for legislative action. Another solution to the staffing crunch is civilianization, i.e. moving sworn officers off of desk duty and replacing them with non-sworn employees, who don’t require the same specialized training and so draw from a larger labor pool.

But these only get you so far. At current margins, the balance is that it’s easier to negotiate with protections rather than dollars, so employers will continue to do so. Which means, to return to the original point, that you probably can’t maximize the good and minimize the bad associated with unions.

Beware the Policy “One Weird Trick”

Police misconduct, and particularly police homicide, is a high-salience policy problem. It is, I feel obliged to note, salient well out of proportion to the actual scale of the problem.10 But it attracts a great deal of attention, both in public and among policymakers, and drives a great deal of political energy.

High-salience policy problems tend to attract “one-weird-trick” solutions. Salience makes the problem politically intractable, because a marginal improvement in the situation is not proportional to our intensity of feeling about it. Simple but comprehensive solutions promise to break the deadlock—except, proponents of them tend to argue, because the shadow-y powers that be don’t want them to.

And because it is high-salience, the problem of police killings attracts a lot of one-weird-trick solutions. If only we could abolish qualified immunity (as my colleague Rafael Mangual has ably explained, QI is mostly a red herring). If only we could “demilitarize” the police (Ralf covers the evidence on the effects of 1033 transfers here—another goose egg). If only we could abolish police unions.

Part of the takeaway from this post should be that reforming police unions per se is not an obvious pathway to reducing police misconduct. But another should be that “one weird trick” solutions, which identify one determinant of the policy-relevant outcome as the comprehensive cause of our problems, should be regarded with suspicion.

That doesn’t mean we should always reject them—I am sympathetic to the idea that many bad outcomes are downstream of housing supply controls, for example—but we should approach them with caution. They are too often too neat to really tell the full story.

For conservatives, the logical proof is a simple one:

• public sector unions are bad;

• police unions are public sector unions;

∴ police unions are bad.

In essence, not only do police have the right to form a union, and not only is the government permitted to bargain with it, but they are affirmatively obligated to do so.

Technically they have region-by-year and urban-by-year fixed effects, but I’ll take it.

Franklin Zimring, When Police Kill (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 26-27.

The ARC review also mentions Rad 2018 (a Masters thesis by the author of the aforementioned review!) as an example of quantitative evidence. But I omit it here because it simply observes a positive relationship between Rad’s extremely complicated index of police protections (researcher DFs, what’s that) and police misconduct in the Mapping Police Violence dataset, with a few controls thrown in for good measure. That ain’t quasi-experimental, folks!

Dharmpala et al. actually say their work doesn’t contradict Goncalves:

In contemporaneous work, however, Goncalves (2019) uses a similar dataset from Florida (along with a national database of fatal incidents) to analyze the impact of unionization on police misconduct. His empirical strategy involves comparing Florida agencies in which unionization elections are successful to those with unsuccessful elections and does not exploit the variation in collective bargaining rights that Williams created. Using this approach, Goncalves (2019) finds statistically insignificant and relatively small effects of unionization on misconduct. In Section 4 below, we discuss the relationship between this paper and Goncalves (2019) in detail and seek to reconcile the contrasting findings. While Goncalves (2019) has a different research question and empirical strategy, there are clearly some overlapping elements. We conclude that our results are fairly consistent with Goncalves’ (2019) where they overlap, but that the Williams quasi-experiment provides a valuable source of variation for understanding the impact of collective bargaining rights.

Cunningham et al. also respond to Goncalves, though I think their response is, as the kids say, cope:

Our work differs from Goncalves (2020) in at least three important ways. First, we focus on deaths by race while he focuses on aggregate deaths, which may mask heterogeneity in police use of lethal force. Second, our research examines a different treatment: the duty to bargain with law enforcement officers’ unions. The duty to bargain may not only strengthen the local power of unions that ultimately establish themselves, but it may also have spillover effects on non-unionized departments within the same state. Finally, we focus on the time period before his begins - one with a rapid increase in police violence.

You don’t know who Gary Becker and George Stigler were? Okay, open a new tab. Go read their Wikipedia articles. Got the gist? Great, back to reading.

The old Graham Factor substack (sadly still on hiatus) had a good post on this.

I mean, okay, technically you don’t. You can put your PD in federal receivership, void the contract, and give cops no complaint protections. States can’t void contracts legislatively, because of the Contracts Clause, but you could also set legislative or state-constitutional limits on the terms of future contracts. But if you do that, you’ll dramatically reduce the “price” you’re willing to pay for policing, and in turn will buy both less quantity and quality of policing. There are some people who think this is good, because they think policing is bad, and those funds should go to the NGO industrial complex alternative methods of crime control. I think these people are at least wrong, and often lying (including to themselves) for self-interested reasons. But that’s a different post.

The number of hard-to-justify police killings every year is small, the number of unambiguous homicides is smaller. The average unarmed black man is more at risk of dying on a bicycle than he is of being shot and killed by the police. 98 percent of police-civilian contacts end peacefully; even in those that don’t, 30 percent of the civilians on whom force was used think the use was justified. Again, my colleague Rafael is good on this, but really it is an argument that requires its own article, which is why it’s getting glossed in a footnote.