Grants Pass Isn't About Housing. It's About Camping.

What people aren't getting about the camping ban case

On Friday the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Grants Pass v. Johnson. That decision reversed a prior Ninth Circuit ruling that municipalities could not enforce anti-camping laws while they lacked enough shelter beds to service their homeless population. That prohibition, originally established in Martin v. Boise, was based on the infamously liberal Ninth’s interpretation of the Eighth Amendment. The idea was that banning people from sleeping outdoors when there were not enough shelter beds constituted “cruel and unusual” punishment. The effect was to prohibit anti-camping enforcement in much of the western United States, where roughly half the nation’s homeless people live. (SCOTUS declined to take up Martin, but Grants Pass had the effect of overruling Martin as well.)

The Grants Pass decision has provoked two related arguments from its critics. One is that camping bans—arresting people for living and sleeping in public—are “cruel and unusual,” regardless of the original public meaning of that phrase.1 The other is that camping bans are not a solution to the problem of homelessness. As the ACLU put it, “We cannot arrest our way out of homelessness.” The Atlantic’s Jerusalem Demsas neatly captured both sentiments in an essay representative of the genre, writing that “[t]he ruling epitomizes why housing has become a crisis in so much of the country: It does nothing to make communities confront their role in causing a housing shortage, and it upholds their ability to inflict pain upon that shortage’s victims.”

Both arguments are wrong, and I think wrong in revealing ways. The purpose of camping bans is not, and has never been, to stop homelessness. Their purpose is to prevent public encampments, which at scale can and do cause serious harm to their residents and to the public. More fundamentally, it is only possible to view such enforcement as “cruel and unusual” by focusing on the rights of the singular camping individual, rather than imagining the harms done by such behavior at scale, and the right of the community to prevent such harms. That dichotomy—between an individual’s right to be deviant2 and the community’s right to be free from the harms of systematic deviance—is, I think, central to the dispute here, and indeed to many disputes about social policy governing deviance.

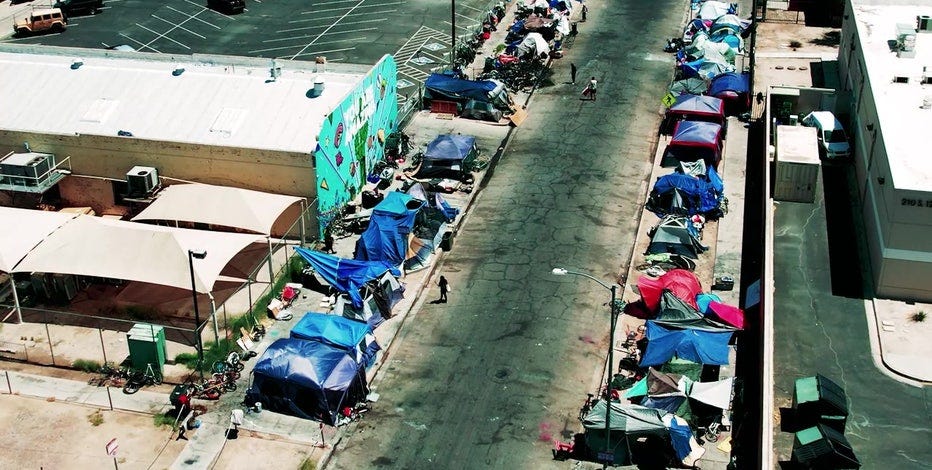

To understand why, I want to talk for a second about The Zone. Until a judge declared it a public nuisance and ordered the city of Phoenix to clear it, The Zone was a massive encampment, which at its peak played home to over 1,000 people and spanned 15 blocks. The plaintiffs who sought to have the nuisance remedied blamed its emergence on Martin, alleging that the city had begun shifting homeless people there following the ruling. Lacking shelter space, they alleged, the city simply moved to a benign containment strategy designed to comply with the Ninth Circuit’s notion of “cruel and unusual.”

But was it humane to create a situation in which people lived like this? According to the court which ordered The Zone cleared, violent and property crime had surged in the area. So had public drug use and “biohazards.” Businesses operating in the area faced, as my colleague Judge Glock writes, “outdoor defecation, public masturbation and sex, fires that incinerated trees, and methamphetamine use around the establishment.”

The Zone is an extreme example of a more specific phenomenon: a dramatic increase in concentrated unsheltered homelessness. Large tent encampments have sprung up from Portland to D.C., containing not just one or a few people, but a dozen or more. This increase was precipitated in part by COVID, when cities temporary shuttered shelters to slow the spread, pushing their homeless populations out on to the streets. But it was also, at least on the west coast, caused by the effects of Martin. As Glock notes, in the year Grants Pass was handed down, homelessness increased by 25% in the Ninth Circuit, even as it declined in the rest of the country.

There is a tendency to view such encampments as mere concentrations of dysfunction, with the implication being that dispersing the camp will not address the associated problems. But in a 2010 paper, Penn’s Richard Berk and John MacDonald show that a large-scale camp clearance program undertaken by the LAPD in Los Angeles’s Skid Row significantly reduced crime in the treated police division compared to control divisions. They see no evidence of displacement. Take apart the camp, and violence, theft, and disorder decline—implying the camps don’t just concentrate, but cause social problems.

There are good reasons why this should be the case. Encampments are human communities, and like human communities, they benefit from economies of scale. One tent is perhaps unsightly. Five tents create opportunities for cooperation; ten, for specialization. Economies emerge: over time, drug dealers and pimps are attracted to concentrations of potential buyers. Moreover, because the encampment is—by definition—not a place characterized by adherence to social norms, dangerous detritus rapidly builds up, and disease spreads. Interpersonal conflict, too, emerges. As Glock writes, “By one estimate, over 40 percent of the shootings in Seattle are linked to homeless encampments, despite the homeless being a small fraction of the city’s overall population. As others have pointed out, the main victims of these acts of violence are other homeless people. About 25 percent of Los Angeles’s murder victims are homeless, for example, though they make up about 1 percent of the population.”

It’s also the case that the larger the camp gets, the harder it is to remove it. Clearing one person’s tent takes far less manpower than clearing 20 or 30 tents; when manpower is constrained, concentrating it for a tent clearance operation gets harder as the operation gets bigger. And that’s not even counting the political power that can be associated with a large encampment, which can attract homelessness advocates litigating on behalf of residents’ “right” to take over public land. Consequently, the best camp control strategy is prevention, not remediation.

When critics of Grants Pass imagine camping, they are often envisioning the lone camper, harassed out of town by the small-minded cops. I am sure that this happens. But the reason that progressive cities like San Francisco, Phoenix, and Los Angeles asked the Supreme Court to overturn Martin is not because they wanted to rough up a single homeless guy. It’s because they wanted the power to clear tens, or hundreds, or thousands of people who had set up their own community within, but not fully bound by the rules of, the city around them. And they wanted the power to ensure that such tent cities do not arise again, even if their shelters are at capacity.

Some object that even such clearances are not tolerable so long as shelter does not exist. Where exactly are the involuntarily unhoused supposed to go? Sleeping, after all, is a necessary biological function—the core of the Martin argument was that punishing someone for something they had to do is cruel and unusual. One rebuttal to this, of course, is that in many cases necessity does not yield a categorical right.3 As members of the Court noted during oral arguments, defecation is a necessity, but no one would (yet) oppose a ban on doing so in public.

But the more persuasive argument, I think, is that while displacing a single camper might be unjust, scaling that phenomenon yields its own unjust configuration. Even those who blanch at the former should be able to look at the encampment—a dangerous, violent, unhealthy place—and conclude that the government has a legitimate interest in abating such an inhumanity, even without having a bed for every single resident who wants one. The critics of Grants Pass choose to focus on individual deviant behavior, and to frame the punishment of that behavior as a deprivation of liberty. What they disregard—what they often fail to see—is that when you scale that behavior, the community’s liberty is also implicated.

A couple of years ago, I was asked to participate in a symposium in The American Conservative on precedents that the Supreme Court could revisit. Specifically, I wrote about Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville, the first of a long series of cases attacking vagrancy laws in the United States. As I wrote then:

Whatever the purpose, the effect [of Papachristou] on law enforcement was profound. Vagrancy statutes were used to corral not just communists, but any individuals disrupting public order. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, in their famous article on “broken windows,” wrote that vagrancy laws “exist not because society wants judges to punish vagrants or drunks but because it wants an officer to have the legal tools to remove undesirable persons from a neighborhood when informal efforts to preserve order in the streets have failed.” …

[T]he order-keeping function of policing, which entails frequent judgement calls, is necessarily vague, which is to say largely an exercise in discretion. The Court saw that this discretion was at odds with a strict liberal theory of due process rights, and so set about to kill it. In so doing, it prioritized the rights of the few over the good of the many. “Arresting a single drunk or a single vagrant who has harmed no identifiable person seems unjust, and in a sense it is,” Wilson and Kelling put it. “But failing to do anything about a score of drunks or a hundred vagrants may destroy an entire community.”

This, incidentally, is what broken windows actually means: that disorder can create further disorder, until a tipping point is reached, causing total loss of social control. The function of the formal systems of social control — i.e. policing — is to prevent that process from initiating, by ensuring that society is able to regulate itself.

And Kelling and Wilson’s point applies quite naturally to camping. The single drunk, or single vagrant, or single camp can do little harm. But when we think exclusively in terms of the rights of the single person in that tent, we become unable to imagine the ways in which repeated over and over again, the pattern of encampment becomes untenable, destructive both to its residents and to the community as a whole.

Demsas and co. are of course right that the solution to homelessness is building more housing. I am happy to permit construction until transient homelessness is a thing of the past. But until that happens—and if it happens, it will not be for some time—cities have every right to and interest in stopping deviant behavior at scale. That’s what’s at stake: the problem isn’t housing, it’s camping.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who wrote the Grants Pass decision, has done in my view yeoman’s work in reigning in the ever-expanding “cruel and unusual” clause. His Grants Pass decision, e.g., relies on his majority opinion in Bucklew v. Precycthe, which offers one of the first coherent Originalist definitions of “cruel and unusual.”

meant here in the descriptive sense of “deviating from commonly accepted norms of behavior,” not necessarily in the pejorative sense.

Actually, as a lawyer friend observed to me after I tweeted about this, necessity is a defense in common law. What Martin actually did was shift the burden: instead of the defendant having to show in court that his illegal act was undertaken out of necessity, his act was instead *assumed* to be a necessity simply by virtue of the number of beds (and, eventually, the number of beds in non-religious facilities) available in the jurisdiction, without regards to other mitigating factors.

I found this article on the Free Press. Well written, thank you. I'd just add Shellenberger's point that "homeless" is really a euphemism for "drug addict" (co-morbid with mental health issues). Again and again in the media I see the lie that the "homeless" increase is solely due to a housing crunch. This is absurd. I don't know any normal adult that would say, "Well, since my rent went up 8% I decided I'll start doing drug cocktails of unknown origin that make me completely lose my mind, become a hoarder of garbage which I'll pile up on public sidewalks, rob my neighbors, start stabbing and shooting people, light stuff on fire, and actively avoid my own family members and the plethora of city services available to help me". I honestly don't believe that more housing is the primary tool here. In SF it's normal for 5 grown adults to all be renting rooms in one apartment. It's not great, SF's housing policies are garbage, but normal people adapt to higher prices/demand by getting less for their money, or moving to locales that cost less, or temporarily moving in with family members, or in the worst case going to shelter because they aren't doing drugs and will be admitted. In the most affluent society in human history, people still have options and people adapt even in the midst of price increases. The idea that moral depravity on the streets is the next step from a rent increase is patently absurd. On the other hand, addicts move across the country to expensive but lawless cities to do drugs, especially when they decriminalize them, again as Shellenberger has shown. One need only take a walk and talk to ACTUAL "homeless" people in any west coast city to prove this very quickly. Advocating for "the homeless" is linguistic jui-jitsu that is really about defending the same woke ideology that is appearing everywhere, and at base seems to be about nihilism itself, a glee in the destruction of the West generally including all merit, property ownership, and "privilege" of any kind. I'm a psychotherapist. To the extent these individuals are indeed "victims" of early life trauma which led to addiction, the absolute last way I'd "treat" these individuals is by letting them rot in the streets, as hundreds of thousands of people slowly kill themselves. It would be insane to write up such a treatment plan for the struggling clients I love and yet this is standard public policy across the United States.

Great post!