How I Changed my Mind About Marijuana

The Case for Prohibition

I have a secret to confess: I was a teenage libertarian.

This is not, if you know the timeline, all that surprising. I graduated from high school in the spring of 2012, three years into the Tea Party movement and amid Ron Paul’s second internet-breaking campaign for the GOP nomination. The “libertarian moment” was steadily rising. If you were young and online, you were a libertarian, and I was both, so libertarian I was.

I was not, it should be added, a fair-weather libertarian. I read End the Fed, yes, but I also read all the books the guys at the Mises Institute shove at you. I somehow consumed all of Murray Rothbard’s interminable manifesto For a New Liberty. I still own, somewhere, a copy of Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, a book I read but surely did not understand. (One of the symptoms of teenage libertarianism is pretending to understand monetary policy.) A teacher once gave me a poor grade in AP European History when, on a test, I deviated from reciting the standard explanations for why the Soviet Union failed for a long discussion of the economic calculation problem. (This, I maintain, was a perfectly reasonable thing to do.)

One of the things you do when you’re a libertarian is support drug legalization. Only a fool could think drug prohibition was a good idea! Marijuana, especially, should obviously be freely available. Not that I partook—you don’t get invited to the cool kids’ parties when you spend your time spouting off about Murray Rothbard. But it was the principle of the thing.

Last November, I joined one third of my fellow Marylanders in voting against Ballot Question 4, which asked whether we supported the legalization of adult-use recreational marijuana in the state. It was, I freely admitted at the time, something of a futile gesture, a sense confirmed by the lopsidedness of the vote. Opposing marijuana legalization is like being a libertarian—passé. Two in three Americans think pot should be legal, including four in five of my fellow under-30s. Even two-thirds of conservatives under 30—both ways I would describe myself—favor legalization.

It is almost certainly the case that my opposition to legalization, like my youthful libertarianism, is driven by an instinctual contrarianism. But it is also, I would like to think, the product of a sober estimation of the costs and benefits of the policy, a comparison of what legalization has promised and what it actually delivered. It is that estimation which this essay lays out: that the arguments for legalization are mostly bad; that the harms of marijuana are, though not overwhelming, significant and probably debilitating for a large minority of the population; and that marijuana legalization will exacerbate, rather than alleviate, the cumulative harm of marijuana.

The War on Drugs Is a Red Herring

It’s sort of telling, I think, that the most commonly used arguments for legalization are not about marijuana per se. They are mostly about the harms of criminalization, and the way in which those harms fall disproportionately on black and Hispanic people. There have been, the argument goes, 15 million marijuana arrests since 1995; half of drug arrests (in 2010) were for marijuana, and 9 in 10 of these were for possession. Moreover, non-white people report consuming marijuana at similar rates to white people, yet are arrested for marijuana offenses at much higher rates. All this criminalization must do more harm—and contribute more to America’s sky-high incarceration—than the counterfactual in which we simply legalize, tax, and regulate weed.

But looking more closely at the data convinced me that this is probably not true.

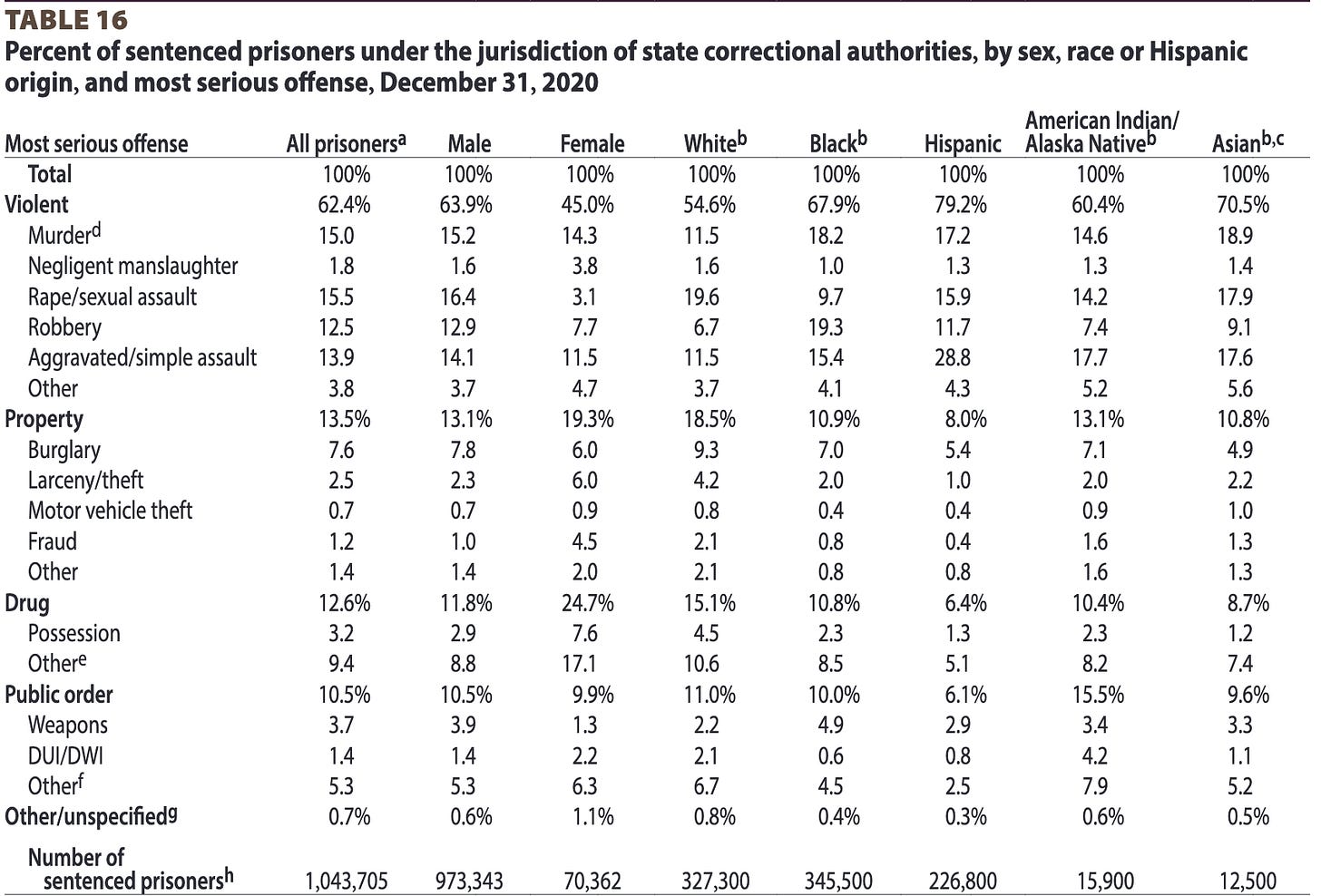

Start with mass incarceration. America does, indeed, incarcerate a lot of people, something like 0.6% of our population, more than basically any other country with credible numbers. A conventional line—one I long believed—is that drug criminalization, and especially marijuana criminalization, drives the scale.

The data tell a less straightforward story. As of the most recent estimates, drug offenders account for a bit more than 12 percent of all state prisoners (which themselves make up about 88 percent of the prison population). They’re a larger share of the smaller federal prison system (46.7 percent), but cumulatively they still account for just 16.7 percent of all prisoners. Possession offenders, in turn, are a smaller share yet—3.2 percent of state prisoners and essentially no one in the federal system (and many possession offenders likely pled down from trafficking). And this is, of course, looking at all drugs, not just marijuana. It’s hard to estimate how many people are in on marijuana-related charges, but John Pfaff—the Fordham law professor and radical pro-decarceration advocate—ballparks it at around 1 to 2 percent of sentences.

There is a stocks-and-flows issue to consider here. Drug sentences are shorter, on average, so even if there are more of them, fewer drug offenders might be in prison at any given point in time. The pseudonymous data analyst Xenocrypt has some good analysis here; he estimates drug sentences account for about 38 percent of the increase in prison sentences over 1977 baseline.

There are a couple of replies to this concern. One is to contest it: Pfaff looks at data from 2000 to 2012, and estimates that “the fraction of unique people passing through for drugs was between 20 and 25 percent, right around the 20 percent who were in prison on any given day during the period examined here.”1 Another is to observe that the share has been steadily declining, even in the absence of legalization—clearly, we did not need to legalize to substantially reduce the drug-sentence share. And a third is to observe, again, that marijuana is only a small fraction even of drug sentences; if it's 10 percent, then we could estimate that marijuana explains about 4 percent of the increase in prison sentences.

Perhaps because the statistics on incarceration don’t suit their narrative, advocates of legalization tend to lean on the arrest statistics. And they are, indeed, troubling. In 2020, for example—a year in which total arrests fell!—police departments reported 226,748 marijuana possession arrests and 23,139 sales arrests to the FBI. There were about 5.5 million arrests reported that same year, meaning marijuana was involved in roughly 1 out of 20 arrests. If we legalized weed, we would expect arrests to fall by about 5 percent, which would mean 5 percent fewer police-civilian interactions, right?

The thing is, recreational marijuana legalization doesn’t actually appear to reduce overall arrests. Here’s a quick analysis (R code) to support that claim:

The FBI publishes counts of arrests across a variety of types of offense every year. (For this analysis, I use a cleaned version of the FBI’s data assembled by Princeton crime data guy Jacob Kaplan and hosted by ICPSR.) One way to estimate the effect of marijuana legalization on arrests is to use what’s called a “two-way fixed effects” (TWFE) analysis. To put it very succinctly: a TWFE uses data that observes multiple units (in our case states) over time, some of which get treated (in our case, legalize recreational MJ) throughout the observation period. We use regression analysis on these data to estimate the effect of the treatment after controlling for (essentially) unit and period (i.e. state and year). In principle, by controlling for everything else, all that’s left over is the effect of treatment.2

So what happens when you estimate the effect of marijuana legalization, accounting for state and year “fixed effects,” on marijuana arrests? Unsurprisingly, arrests for marijuana-related offenses—possession and sales—plummet.

Figure 2 reports the regression results.3 Just zoom in on on the values next to TreatedTRUE, the coefficient. Legalization, in this estimate, is associated with 1,011.1 fewer marijuana sales arrests and 6,665.9 fewer marijuana possession arrests per state-year. The second two columns repeat the exercise but with the outcome variable logged, which is a quick and dirty way to get the effect in percentage terms.4 In our case, legalization is associated with a 56 percent decrease in cannabis sales arrests and a 70 percent decrease in cannabis possession arrests. All the results are statistically significant (p < 0.001).

But what about arrests generally? Figure 3 repeats the same exercise, but this time looking at a) total number of arrests in a state-year and b) total number of arrests of black people in a state and year. Legalization, it suggests, is associated with about 4,600 more total arrests in a state-year, and 7,187 additional black arrests specifically. (The latter estimate is significant at p < 0.01.) In percentage terms, legalization is associated with an 11 percent increase in both arrests generally and black arrests specifically (neither significant). In other words, marijuana legalization has no statistically significant effect on total arrests or, possibly, actually increases arrests.

This is a rough and dirty analysis; I wouldn't publish it in a journal, or indeed probably anywhere other than Substack (or Twitter).5 But it makes sense ex ante, I think.

Why? Return to the observation that very few people go to prison for marijuana, particularly marijuana possession. If there are lots of people being arrested for marijuana possession, but none of them is getting prosecuted or imprisoned for it, why do cops keep arresting them? One answer is, of course, cops get off on it. But another, more parsimonious one (if you think hundreds of thousands of cops actually just spend all day busting pot smokers for fun, I don’t take your understanding of the situation seriously) is that marijuana possession (and the smell of pot) is a pretext for cops to stop and search people they think may have committed other crimes, and marijuana possession similarly a pretext to arrest someone. If marijuana arrests are mostly about pretext, then it would make sense that cops simply substitute to other kinds of arrest in their absence, netting no real change in the arrest rate.

The bigger point, though, is that legalizing marijuana doesn’t have much of an effect on either incarceration or arrest. It doesn’t appear to do much for criminal justice involvement at all. If the whole case for legalization is that marijuana prohibition is a major problem for our criminal justice system, then the case doesn’t look that strong.

Yes, Marijuana Has Benefits

But, to be fair, that’s not the whole case. Some of it rests on the merits of marijuana itself.

One variation on this argument is that marijuana’s psychoactive ingredients have medical benefits. These are, I think, often overstated—ask your local dispensary and they’ll tell you there’s little marijuana doesn’t cure. Bracket, too, that smoking marijuana is a fairly inefficient way to dose for therapeutic effects (as NIDA puts it, “Researchers generally consider medications … which use purified chemicals derived from or based on those in the marijuana plant, to be more promising therapeutically than use of the whole marijuana plant or its crude extracts”). Granting all that, there are absolutely cases where marijuana is indicated as a treatment: chronic pain, MS-related spasticity, and for controlling nausea and vomiting in adults undergoing chemotherapy. The FDA has also approved Epidiolex, a childhood epilepsy treatment, the active ingredient in which is cannabidiol (CBD).

That the FDA is now approving marijuana-related substances for medical treatment is perhaps a reason to reconsider marijuana’s place in the schedule of controlled substances, where it is currently labeled as having “a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision.” But to infer from these medical benefits that recreational marijuana should be legalized is a step too far. There are, after all, medical benefits to cocaine, opioids, and amphetamines, yet most people do not take this as a justification for legalizing “recreational” variants of these substances.

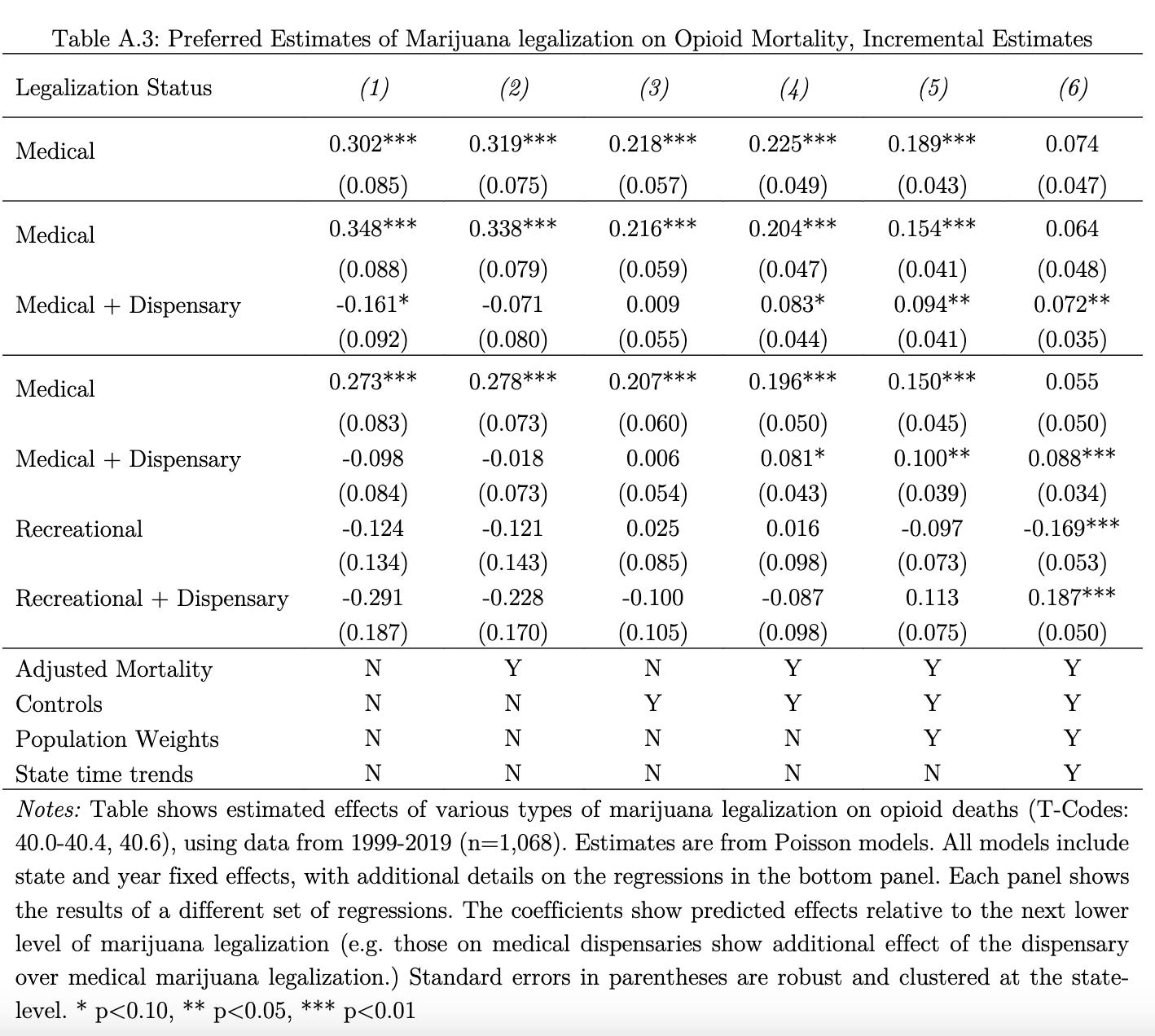

A variation on this argument is that legal marijuana is beneficial because it is an effective substitute for other, harder drugs. Marijuana is indicated for chronic pain, e.g., and making it easier to access might therefore reduce dependence on opioids—which, let it be acknowledged, were involved in the lion’s share of the more than 100,000 drug overdose deaths last year.

There was, indeed, some evidence that legalization states were doing better in the opioid epidemic than non-legalization. More recent research, though, suggests the sign has flipped: a working paper from Neil Mathur and Christopher Ruhm extends prior analyses to incorporate the expansion of marijuana legalization. They find that “legal medical marijuana, particularly when available through retail dispensaries, is associated with higher opioid mortality. The results for recreational marijuana, while less reliable, also suggest that retail sales through dispensaries are associated with greater death rates relative to the counterfactual of no legal cannabis.”

Their results vary depending on specification, so it’s possible to dismiss the positive relationship between marijuana and opioid deaths. But it is relatively hard to look at the data as they currently exist and conclude that opioids are a good substitute for opioids.

Beyond its medical or socially beneficial applications, I think there are two related and very straightforward reasons to legalize marijuana, ones which do not often feature in the debate but which obviously influence it nonetheless. These are 1) by default, people should be able to do what they want with their bodies and 2) marijuana is fun, and fun things are good.

I actually find these arguments more persuasive than the preceding legal and medical arguments. I’ve consumed marijuana a handful of times, and while those experiences weren’t incredible, they weren’t unenjoyable. And in general, Americans tend to think that people should be allowed to do fun stuff, even when it might have downsides.

That’s a presumption, but it’s a rebuttable one. We place restrictions on or otherwise prohibit all sorts of fun things—cocaine is a lot of fun!—because we conclude that the harms outweigh the benefits, and the harms can’t be sufficiently mitigated to entail the benefits obtained. And the benefits of marijuana legalization are not all that great, over and above that—again—pot is fun. But what costs justify curtailing that acknowledged benefit?

Marijuana Has Costs Too

There is a popular perception—routinely exploited by advocates of legalization—that the harms of marijuana usage are, if not nonexistent, at least dramatically exaggerated. And they are right, of course, that at times in our history proponents of prohibition have gotten out over their skis. Overcorrecting for that failure, however, has led us to assume that marijuana can do no harms.

But of course there are substantial harms associated with marijuana, just like any other intoxicant. In the short run, consuming high-enough doses can lead to paranoia, tachycardia, hyperemesis (read: throwing up a lot), and acute psychosis (although mostly in children). There are also longer-term concerns, primarily for mental health. Marijuana use at sufficiently high levels may be associated with heightened anxiety and depression, though the evidence there is weak and could plausibly reverse the direction of causality (anxiety and depression cause marijuana use, i.e.). More persuasive is the link between heavy marijuana use, particularly in adolescence, and psychosis, including schizophrenia (Though that too is not without debate). Marijuana consumption can also lead to externally harmful behaviors, much like any other intoxicant. 40 percent of past-year users admit to driving under the influence of marijuana in the past month.

More generally, marijuana is, as drug policy scholar Jonathan Caulkins once described it, “a performance-degrading drug.” It lowers motivation, makes (some of) its users slower, more dull, less engaged with the world. One piece of experimental evidence for this (in case you need convincing) comes from Marie and Zölitz (2015), who exploit a policy change in which the city of Maastricht prohibited people from most foreign countries from buying pot in its marijuana cafes. Using a double-difference strategy not unlike the one I use above, the paper compares the grades of native and foreign MU students before and after the change. Unsurprisingly, “the academic performance of students who are no longer legally permitted to buy cannabis increases substantially,” with improvements equivalent to about a tenth of a standard deviation in standardized exam scores.

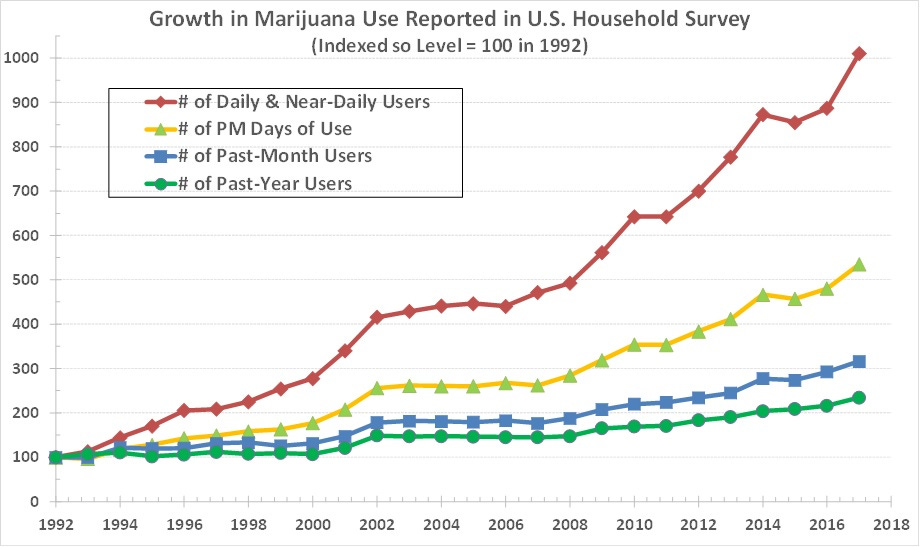

That marijuana has harms is not necessarily sufficient reason to regulate or prohibit it. But those harms are not evenly distributed across the population. Rather, they are concentrated in the subset of the population who suffer from marijuana addiction (or “marijuana use disorder”/MUD), characterized by “continued use of cannabis despite significant negative impact on one's life and health.” By best estimate 14.2 million Americans suffered from an MUD in 2020, compared to just shy of 50 million who used marijuana.

Consumption of marijuana (like every other addictive substance) is power-law distributed. That is, a small percentage of its users—10 to 20 percent—account for the lion’s share—80 to 90 percent—of use sessions. As the above figure shows, while the share of the population using marijuana ever or monthly has risen somewhat over the past several decades amid liberalization, the share of the population using heavily has grown substantially. As marijuana becomes more widely available, the extent and intensity of marijuana addiction will necessarily rise. Some MUD sufferers will experience debilitating physical or psychological effects. But many of them simply find their lives falling apart, as Annie Lowrey ably documented in The Atlantic five years ago:

Users or former users I spoke with described lost jobs, lost marriages, lost houses, lost money, lost time. Foreclosures and divorces. Weight gain and mental-health problems. And one other thing: the problem of convincing other people that what they were experiencing was real. A few mentioned jokes about Doritos, and comments implying that the real issue was that they were lazy stoners. Others mentioned the common belief that you can be “psychologically” addicted to pot, but not “physically” or “really” addicted. The condition remains misunderstood, discounted, and strangely invisible, even as legalization and white-marketization pitches ahead.

Synthesize these concerns—marijuana has short- and long-term harms, it’s generally “performance-degrading,” and these effects concentrate in a small, addicted subset of the population—and you begin to see the way in which marijuana is a social problem. It is not, I think, a problem on the scale of, say, fentanyl. But something does not need to be massively deadly before it merits policy attention, particularly if the case in favor of its availability is, more or less, “people like it, leave them alone.” If it leaves a substantial portion of the population addicted, suffering harms to their health and livelihood, then “many people also enjoy it” does not seem to be an adequate retort. We should at the very least want it controlled in some way, if not prohibited outright.

The Regulatory Rock and Hard Place

One of the basic insights of modern theory of drug regulation is that when it comes to regulating addictive substances, an inefficient market is often preferable to an efficient one. The profit motive and addiction tend to go poorly together: Because consumption of addictive goods is power-law distributed, 20 percent (or fewer) of consumers will account for 80 percent (or more) or profits. And it is in the best interest of profit-seeking firms to try to maximize consumption within this population—regardless of social externalities or individual “internalities.” Indeed, competitive pressure means that even if one firm abstains from taking advantage of the addictive nature of their product, it will tend to lose out to others that do.

Drug policy scholars have spent a lot of time thinking about how to design drug control regimes which minimize the harms, external and internal, of some drugs while permitting their sale. Way back in 1992, Mark A.R. Kleiman—the late drug policy scholar who god-fathered the modern theory of drug market design—proposed a tightly controlled system of distribution of marijuana, with users licensed and consumption limits strictly imposed. He even suggested that marijuana only ever be sold by mail, so as to maintain the integrity of the system.6 Since then, various approaches (see figure 6) have been contemplated, including non-profit grow co-ops and marijuana "state stores." Effective marijuana tax policy, similarly, is thought to entail imposing an aggressive Pigouvian tax to offset the social costs of marijuana use.

The optimal legalization regime—the one which mitigates the individual and social harms of marijuana—is, in other words, almost certainly stricter than any prevailing in any of the legalization states. It imposes substantial costs, in terms of both taxes and regulations, on marijuana. These costs, in point of fact, we should expect to be most of the cost of marijuana to the end user in a legal system. Weed is, well, a weed—production costs are trivial, particularly when modern, big ag. is doing the producing. Most of marijuana’s current cost is a function of prohibition; after legalization, most of its cost will still basically be regulatory.

The problem, though, is that we are not building a licit market from the ground up. Rather, there is a pre-existing illicit market, one filled with entrepreneurs who are well-versed in dodging the law. If prices rise too high, through regulation or taxation, users will simply substitute to the illicit market. Caulkins again:

The RAND Corporation's Drug Policy Research Center surveyed heavy marijuana users about where they'd buy drugs under various scenarios, and how much they would be willing to spend. While a few ethical or risk-averse people said they'd pay much more for marijuana that is "legal, labeled, and tested for pesticides and other contaminants," most wouldn't pay more than a few dollars per gram over the black-market price; people who said they'd buy whatever was cheapest accounted for fully one-third of consumption.

And in fact, we now know this is exactly what is happening. Agricultural economists Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner, in their recent book Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics, use evidence from more than 30 million publicly advertised retail weed prices to estimate that the costs of unlicensed weed is up to 50 percent lower than that of licensed weed. Three years into California’s legalization, they find, only a quarter of weed is bought from licensed dispensaries. “In many states,” they write, “it is not clear whether the price of legal weed will ever be competitive with the price of illegal weed for most consumers.”7

As Goldstein and Sumner observe, this is for the simple reason that legal and illegal weed are near-perfect substitutes, unless you want to pay for quality control—and, per RAND above, most heavy users care much more about price than quality. What is more, the economies of weed mean that the legal market cannot even really compete on production efficiency. When most of the price of a good is regulation, and there is an equivalent but less-regulated and therefore cheaper substitute, it is little surprise that the more regulated product cannot take hold. Indeed, the existence of the illicit substitute appears to be an ineradicable fact of life: even in Colorado, where marijuana has been legal for over a decade under a regime far more lax than the kind Kleiman might have preferred, around a third of weed is still bought from the illicit market.

In my review of Goldstein and Sumner’s book, I point out that their model (legal weed = illegal weed + regulation) is incomplete. Prohibition imposes costs of its own—marijuana businesses lose out on efficiencies today, for example, because they struggle to interact with federally regulated banks—and so does enforcement. So really legal weed = illegal weed + regulation - prohibition. In principle, you could drive the price of illegal weed up by cracking down on unlicensed distributors.

But in political reality, I suspect this is a non-starter. We have spent the past several decades contending that marijuana enforcement is racist, evil, and pointless—there is little appetite for doing more of it. And in general, expecting business regulators to do work that we once reserved to the police would require turning the former into the latter, lest we risk bringing a proverbial water gun to a gun fight. Yet no one seriously advocates for deploying the ATF to shut down unlicensed pot shops.

As a result, regulating our way out of marijuana’s harms traps policymakers between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, a harm-minimizing marijuana market entails high taxation and strict regulation. On the other, it also needs to be cheap enough to outcompete the illicit producers who will otherwise swoop in to provide where the licit market does not—thereby producing the same harms the licit market is meant to obviate. In optimizing between these two extremes, we get the worst of both worlds: a thriving illicit market, and also weed widely available enough to harm millions of heavy users.

Prohibition as Big, Dumb Policy

A theme I hope to pursue in this Substack is the virtue of big, dumb policy. Getting policy right is hard; often, a blunter instrument will have a greater chance of success than a more precisely honed one. This is, I think, particularly true of the United States, with its “weak state,” and weak bureaucratic tradition compared to nations like France or China. Humans are bad at optimization in real time, and sometimes we will be net better off not trying at all.

So it is with marijuana. Caulkins, writing (perhaps tongue-in-cheek) about how to tax marijuana, argues that to truly get it right would require an independent tax-setting agency, akin to the federal reserve, which could precisely target the tax rate to prevailing conditions. This sort of optimization problem is, I think, beyond the ken of most actual policymakers. And even if there is no knowledge problem, there is a straightforward regulatory capture problem—a single, national, independent regulatory agency for the marijuana industry is a ripe target for the jackals of industry.

Which returns us to the virtues of marijuana prohibition. If we cannot optimize the market in a vicious good, perhaps it is better to have no market at all, and to actively prohibit the production and sale of that good. The virtue of prohibition is that it minimizes the extensive margin of harmful use, by increasing price and reducing availability. Indeed, the lesson of marijuana legalization is that the “iron law of prohibition”—essentially, prohibition decreases extent of use but increases intensity as measured by dose—is not so iron after all, insofar as marijuana potency has grown as regulation has slackened. If anything, by keeping big ag. out of the marijuana business, prohibition restricts potency as well as extent of use.

Better, in short, the big dumb policy that works than the smart, targeted one that doesn’t.

I am open to some policy tweaks. Marijuana possession is decriminalized, either directly or via legalization, in 31 states. It has been effectively decriminalized federally since the Cole memo. Possession arrests’s use as a pretext is, in my view, a reason to keep possession illegal; but the fact that cops just substitute to other arrest types suggest that decriminalizing small possession would not have an appreciable impact on police efficacy. Perhaps because I don’t think it would change much, I would be open to decriminalization of possession specifically, if it is part of some broader political exchange. It is also worth exploring changing THC’s scheduling under the CSA, to the extent that THC derivatives—not smoked flower—may have real medical benefits.

But decriminalizing large-scale sales—nevermind legalizing and regulating—entails playing with fire. Perhaps, in a different regulatory world, with a different set of underlying facts, we could do so safely. But as is, I expect mostly that many people will end up burned.

John Pfaff, Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration - and How to Achieve Real Reform (Basic Books, 2017), p. 37.

If this doesn’t make sense to you, that’s reasonable! I’ll ask you to trust me, but if you want to learn more, I recommend Nick Huntington-Klein’s The Effect, particularly chs. 16 and 17.

A variation on this and the next analysis which includes population controls—not, strictly speaking, necessary in this sort of model—returns results of the same direction and significance and similar magnitude.

See here: the percentage-wise change in the DV for a 1 unit increase in the IV is (e^coefficient - 1) * 100.

I didn’t spend a lot of time on data cleaning. Also, I don’t account for the well-established problems with multiple-treatment period TWFE analyses (see e.g. Scott Cunningham’s post here). And I don’t do any of the tests you do with a diff-in-diff design, e.g. examine pre-trends. I do this because I didn’t want to get bogged down in explaining methods even more than I already have. If someone wants to kick holes in the analysis, they are welcome to do so!

Mark A.R. Kleiman, Against Excess: Drug Policy for Results (Basic Books, 1992), pp. 278 - 281.

Robin Goldstein and Daniel Sumner, Can Legal Weed Win? The Blunt Realities of Cannabis Economics (University of California Press, 2022), pp. ix - x.

Not one word about alcohol. What are the chances the author likes to consume alcohol? I'd say pretty darn good.

The house isn't on fire. Get a grip.