Contra Sullum Contra Me

Even more on marijuana

This ‘stack has almost doubled its subscriber count in the last several days. That’s thanks primarily to Ross Douthat, who gave my essay on marijuana an extended treatment in his Wednesday column. To all my new subscribers, welcome.

The mention also means I’ve received a greal deal of pushback, most of it expected. A fair amount of it I’ve let lie. I don’t want or expect this newsletter to be exclusively about marijuana policy—I have drafts in process about fentanyl supply control, the virtues of incarceration, and a vision for markets in prisons, just to give you a sense of the sort of content you can expect.

But I do want to dedicate some figurative column inches to the most high-profile counter-argument, from Reason’s Jacob Sullum. In an essay from yesterday afternoon (that came across my transom this morning), Sullum charges that Douthat and I are wrong, and that (to quote the headline), “Pot Legalization Is a 'Big Mistake' Only If You Ignore the Value of Freedom and the Injustice of Prohibition.”

Obviously, I think Sullum is wrong. But I appreciate a detailed reply from someone like Sullum, who is a thoughtful commentator on the other side. And so I feel like it’s only fair of me to respond in kind.

Let me start with his opening:

New York Times columnist Ross Douthat thinks "legalizing marijuana is a big mistake." His argument, which draws heavily on a longer Substack essay by the Manhattan Institute's Charles Fain Lehman, is unabashedly consequentialist, purporting to weigh the collective benefits of repealing prohibition against the costs. It therefore will not persuade anyone who believes, as a matter of principle, that people should be free to decide for themselves what goes into their bodies.

Let me take this as an opportunity to articulate Sullum’s argument as I understand it. He has two objections to my (and Douthat’s) position. One is that my “consequentialist” (I think this is a fair charge) position on marijuana is wrong on the merits; I am doing the cost/benefit calculus wrongly. There are three sub-objections: that I underrate the impact of marijuana arrests; that I overrate the extent of MUD/CUD and its relationship to legalization; and that I avoid how much risk we are willing to absorb under current alcohol regulation, by comparison to which marijuana control is unreasonable. But even if I am correct, then there is still a second, more succint objection: the principled view that respecting individual autonomy means allowing people to make bad choices.

In other words, here’s our framework of Sullum’s argument:

My “consequentialist” analysis is wrong

Marijuana enforcement is more harmful than I say

Marijuana addiction is less serious than I say

the widespread prevalence of alcohol means that the harms of marijuana are below our threshold of intolerability.

Even if my cost/benefit analysis is right, it doesn’t matter, because “as a matter of principle … people should be free to decide for themselves what goes into their bodies.”

With me? Let’s respond to each piece of the argument.

Marijuana enforcement is more harmful than I say

Sullum concedes that, yes, marijuana prohibition doesn’t really send a lot of people to prison. But, he says, marijuana arrests still generate substantial harm, as criminal records limit access to “employment, housing, and education. Those burdens are bigger and more extensive than Douthat and Lehman are willing to acknowledge.”

Let me offer three responses. One is that Sullum does not both to actually estimate the effects of marijuana arrests on employment, housing, and education. To be fair, that’s no mean feat—I spent a little while looking for analyses and came up dry. But if he’s going to insist that this effect is so dire as to outweigh the harms of marijuana usage, he needs to give me more than aggregate arrest numbers. In the counterfactual where marijuana is legalized, how many more people have employment, housing and education?

Two is that, of course, nothing about this objection means that legalization is a necessary or appropriate remedy. The Biden administration’s pardon of federal possession offenders did not require the legalization of marijuana; nor, more generally, does state or federal decriminalization. To use marijuana possession arrests as a reason to legalize is, ultimately, a rhetorical slight-of-hand: possession decriminalization achieves much the same end without licensing distribution.

But these are small objections against the larger one, which is that I don’t think Sullum got the point of my analysis of the effect of legalization on arrests. What I did, recall, was estimate the effect of legalization on a) marijuana arrests and b) all arrests, using a two-way fixed effects approach to control for everything but the state of legalization/non-legalization. Unsurprisingly, legalization dramatically reduces marijuana arrests. But it has essentially no impact on the overall arrest level, suggesting that cops simply substitute from marijuana arrests to some other kind of arrest, probably as part of a broader strategy of pretext arrests as enforcement.

Sullum’s response to this observation is to say that it’s not the “relevant question.” “Again, unless you trust the police enough to think they are always protecting public safety when they search or arrest people based on ‘a pretext,’” Sullum writes. “eliminating a common excuse for hassling individuals whom cops view as suspicious looks like an improvement.”

Bracket the propriety of pretext policing:1 Sullum’s argument here is a non-sequitur as regards his argument about the harms of marijuana enforcement. Sullum says that marijuana criminalization harms people through the channel of arrest: if you get arrested, you have a record, and you can’t get access to certain things. If legalization reduced total arrests, it would reduce that harm. But if legalization has no effect on total arrests—if cops just substitute to other kinds of arrests and the total arrest level remains constant—then the harms of arrest remain constant. Sullum’s argument for legalization is, first and foremost, that it will reduce the harms attendant to arrests; if legalization doesn’t do that, then it’s not much of an argument.

Marijuana addiction is less serious than I say

My and Douthat’s major concern, Sullum says, is the harmful effects of heavy use, including marijuana addiction. But he casts doubts on both the extent and intensity of MUD. He does so a) by pointing out that the NSDUH is not a clinical assessment, b) that MUD lumps together people with severe and mild symptoms, and c) there’s a big jump in MUDs between 2019 and 2021, which he argues is attributable to COVID.

Sullum is of course correct that the NSDUH is not a clinical assessment. But observing that it may overcount the MUD population share is not much of an argument. The MUD risk I usually see cited is 10 percent, i.e. about 10 percent of users will become addicted. This is consonant with the general observation that 10 to 20 percent of users of almost any addictive substance will account for 80 to 90 percent of use. That there’s a higher share than that in the self-report marijuana user population is, I would conjecture, because marijuana legalization has mostly caused people who use to use more heavily, rather than induce the marginal person to start using. The numerator has grown more rapidly than the denominator.

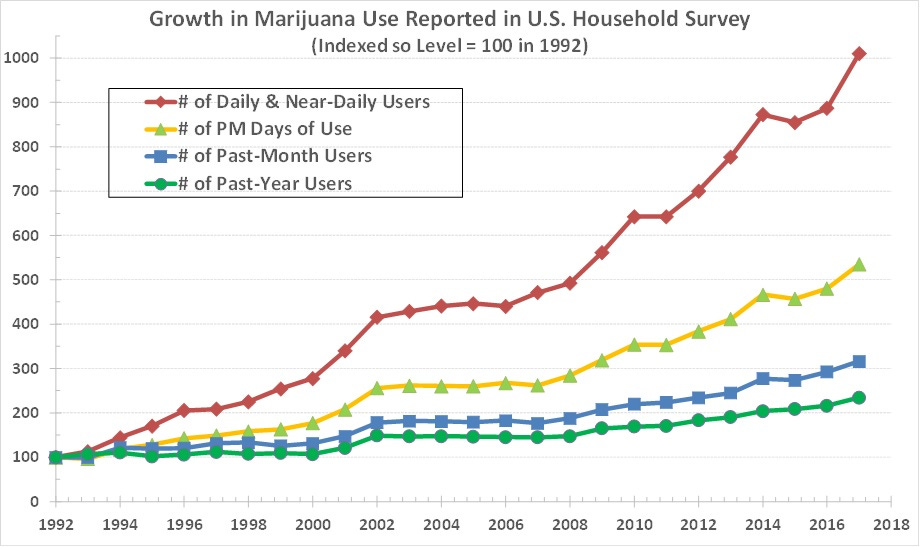

That’s actually the point of this chart, which I include in the original piece, and which Sullum neglects. Okay, sure, more people with MUDs in 2021 vs. 2019 because of COVID. But the long run trend is towards more heavy use, with heavy use rising at a much faster rate than number of ever-users. I am alarmed at the rate at which probably harmful use is growing, an objection to which Sullum’s arguments are largely irrelevant. Yes, maybe there are fewer than 14 million people with a life-altering MUD right now; the point is that if you have a large and flourishing market in marijuana, many more lives will be affected by marijuana addiction than are under prohibition.

But, okay, what about those people who get classified as having an MUD just because they use a lot? As Sullum puts it, '“If you experience ‘a strong urge to use marijuana’ and ‘spend a great deal of your time’ doing so or find that ‘the same amount of marijuana’ has ‘much less effect on you than it used to,’ for example, you qualify for the diagnosis, provided you are experiencing ‘clinically significant impairment or distress’—which, again, the NSDUH questionnaire is not designed to measure.” How significant is this population, actually?

The thing is, the underlying NSDUH data are publicly available, including the self-assessed symptoms that are used to construct the MUD variable. What percentage of people a) are assessed as having a MUD, b) report a strong urge to use AND either spend a great deal of time using OR find that the same amount of marijuana is having much less effect, but c) have no other symptoms? By my ballpark, about 9%.2 The other 91% have some other symptom of a MUD, from minor withdrawal symptoms to marijuana causing family or work problems or putting them in danger. About 20 percent using in spite of marijuana causing problems at home, work, or school, or their use causing them to get hurt or worsening their physical or mental health.3

The NSDUH also estimates the severity of MUD. By my count, about 57% have a “mild” disorder, 27 percent have a “moderate” disorder, and 16 percent have a “severe” disorder. Of course, mild disorders may become moderate or severe — simply observing that the majority of sufferers do not have the worst problems is not a reason to not worry about their wellbeing.

I do want to pause to note that I think Sullum’s rhetorical tactic here is all too common, and should cause you to be skeptical of the strength of his analysis generally. You should “view with caution,” as he puts it, any argument that argues composition of the analyzed population might make the summary statistic less compelling than it seems, but doesn’t actually show that this is true, especially when the data are publicly available. “Things might be otherwise,” without proof that things are in fact otherwise, is perhaps worse than not making the argument at all.

Marijuana is analogous to alcohol

This one is also the standard response I got on Twitter and in the comments section on the post. Sullum:

Even among heavy users, in other words, alcohol is apt to cause more serious problems than marijuana. Yet neither Douthat nor Lehman discuss the potential benefits of substituting marijuana for alcohol. In fact, they do not mention alcohol at all, perhaps because that would raise the question of whether it is sensible to ban marijuana while tolerating a drug that is more hazardous by several measures, including acute toxicity, long-term health problems, and road safety.

Alcohol kills more people, and does more harm, than marijuana. Yet, we legalize alcohol. Doesn’t that mean we should legalize marijuana?

This is a sufficiently common objection that I’d like to give it its own post-length attention. But I’ll do the short version here: the American alcohol situation is, indeed, attrocious. CDC guesses 140,000 deaths per year involve alcohol; alcohol is a major driver of crime. Bluntly, we should regulate alcohol much more stringently than we currently do. Though we no longer prohibit its consumption, we’ve been willing to tighten alcohol laws in living memory: In 1984, Congress compelled all the states to raise their drinking age to 21, a change which, given the robust age-cutoff evidence that being allowed to drink increases crime, almost certainly had a signficant impact on crime nationwide. Other controls, like pegging the alcohol excise tax to inflation or expanding compulsory alcohol testing in probation and parole for related offenses, are almost certainly electorally palatable and would have significant social benefit.

But the claim that because alcohol is sold marijuana should also be sold is a non-sequitur. Different substances are different—the regulatory regime well-suited to one is not necessarily well-suited to another. And my whole argument is that effective, harm-minimizing regulation of marijuana is very hard to do right, such that it’s better to simply not try at all. More generally, two wrongs do not, as they say, make a right. Yes, we legalize alcohol, to often enormous social cost. But internal consistency is not constitutionally mandatory—why should we permit one socially harmful substance just because we happen to permit another?

Autonomy trumps consequence

I mean, Sullum’s answer to the above question is that alcohol regulation and marijuana regulation are both bad, because individual autonomy is more important than mitigating the harms these substances do to a minority of users:

Respect for individual autonomy, of course, has always entailed the risk that people will make bad choices. That is true of everything that people enjoy, whether it's alcohol, marijuana, social media, video games, gambling, shopping, sex, eating, or exercise. Even when most people manage to enjoy these things without ruining their lives, a minority inevitably will take them to excess. The question is whether that risk justifies coercive intervention, which is also dangerous and costly.

Answering that question requires more than weighing measurable costs and benefits. It requires value judgments that Douthat and Lehman make without acknowledging them. When you start with the assumption that government policy should be based on a collectivist calculus that assigns little or no weight to "personal choice," which Douthat dismisses as a mere "banner," you can rationalize nearly any paternalistic scheme, no matter how oppressive or unjust.

Sullum is, I think, equivocating here and throughout the piece. Is autonomy an absolute, inviolable principle? Or is it something that we can weigh alongside other goods? I can’t really speak for Douthat, but I suspect he would agree that we often should respect “personal choice,” particularly in the absence of compelling reasons to do otherwise. But one “compelling reason to do otherwise” is that permitting some people to do something they find fun will also ruin the lives of some other people, with those harms often spilling over into the community writ large.

Indeed, most people think that we should try to balance freedom to choose with mitigating the harms of bad personal choices. We impose and enforce speed limits, control the distribution of alcohol, restrict access to gambling, and so forth. In some cases, we think that the harms are not worth the personal choice—8 or 9 in 10 Americans oppose the legalization of heroin, meth, and cocaine. “But heroin, meth, and cocaine aren’t as bad as marijuana!” the reader might object. Granted. But the point is the principle: personal choice is just one of many goods that we balance, and it often loses out to other concerns. Thinking that it should doesn’t make me a “collectivist,” except insofar as it makes most people and governments throughout history collectivist.

Of course, maybe Sullum believes that personal choice is an absolute, which can be outcompeted by few or no other goods. If this is true, then by consequence marijuana use is an absolute or near-absolute right. But if that’s the case, then trying to poke holes in my cost-benefit analysis is largely pointless, because even if marijuana legalization killed a lot of people, it would still be morally mandatory.

Such beliefs are, I tend to think, at the core of the worldviews of most proponents of drug liberalization. Sullum, the author of Saying Yes: In Defense of Drug Use, would probably more gladly volunteer that this is the case than his more tactically inclined peers. This is because while it may be a consistent view, it is not a particularly popular one—nor should it be.

It’s often good, but I don’t need to convince you of that to convince you of my argument.

To get this figure, I filter out respondents who are assessed as having a past year MUD (PYUD5MRJ == 1). I then use the below horrible boolean kludge to assess if someone falls into Sullum’s group:

no_other_problems = (UDMJSTRURGE == 1 & (UDMJTIMEUSE == 1 | UDMJLESSEFF == 1)) & !(UDMJAVWMARJ == 1 | UDMJAVWOTHR == 1 | UDMJFMLYCTD == 1 | UDMJFMLYPRB == 1 | UDMJGETHURT == 1 | UDMJHLTHCTD == 1 | UDMJLRGAMTS == 1 | UDMJMNTLCTD == 1 | UDMJNEEDMOR == 1 | UDMJNOTSTOP == 1 | UDMJSTOPACT == 1 | UDMJTIMEGET == 1 | UDMJWANTBAD == 1 | UDMJWDANGRY == 1 | UDMJWDAPPET == 1 | UDMJWDCHILL == 1 | UDMJWDDEPRS == 1 | UDMJWDFEVER == 1 | UDMJWDFLANX == 1 | UDMJWDHEDAC == 1 | UDMJWDSHAKE == 1 | UDMJWDSITST == 1 | UDMJWDSLEEP == 1 | UDMJWDSTMCH == 1 | UDMJWDSWEAT == 1 | UDMJWORKPRB == 1 | UDMJWSHSTOP == 1))

The “no other problems” share goes up to 10.5% if you make the first statement the more inclusive “UDMJSTRURGE == 1 | UDMJTIMEUSE == 1 | UDMJLESSEFF == 1”

UDMJFMLYCTD == 1 | UDMJGETHURT == 1 | UDMJHLTHCTD == 1 | UDMJMNTLCTD == 1 | UDMJWORKPRB == 1

Another important "Libertarian" argument is that there are already too many unenforceable laws on the books which the police/politicians can selectively enforce for reasons other than the stated socially beneficial purpose. Like police targeting women for pot to extort sex. Get a cop drunk and ask him about it if you don't believe it. Marijuana use didn't thwart the career of Barack Obama, he didn't let it interfere with his choices and he was pretty successful. But others limited their choices because they worried about persecution. They won't apply for a job because there might be a drug-test. My grandfather went broke during Prohibition because he complied with the law and switched over his Chicago brewery from beer to malted milk, while Busch went to Canada and continued to brew beer. Except for his devotion to obedience to the law, I might have been born into a wealthy family. So, now the girls "vape" their pot so the cops can't smell the smoke...Prohibition is not the answer. What happened when they threatened to prohibit "assault weapons" and "Hi-cap mags"? Thousands of "assault weapons" (with hi-cap mags and billions of rounds of ammo) are out in circulation now that wouldn't have been had they never done it. It turned a previously sleepy market into a "must-have" feeding frenzy amongst people who have absolutely no use for the product- or even know how to use the product. They had to gear up production to meet the increased demand. You can't change anything without it affecting everything. As with lotteries, taxing marijuana gets to be one more regressive tax on a long menu which bleed the poor/ignorant and spare the rich. But people claim regulation benefits the poor! It's all smoke and mirrors.

The two arguments for MJ legalization I think are most persuasive are 1)that keeping it illegal did not mean it was unavailable, 2)and scarce tax dollars were being expended to prosecute & incarcerate offenders. In states with constitutional limits on spending, spending on MJ enforcement meant less money for everything else (k-12 Ed, higher Ed, incarceration of violent offenders, etc.) If the data show that legalization substantially increased it availability to underage users, that would be a point against legalization.