Four Fast Thoughts on Xylazine

Some implications of tranq dope

At some point in the past six months, everyone decided it was finally time to talk about xylazine. In April, the White House officially designated xylazine-adulterated fentanyl an emerging threat, following announcements from the FDA and DEA. States have been moving to schedule it, and Congress seems primed to follow suit.

If this particular string of strange chemical syllables is alien to you, let me get you up to speed. Xylazine (sold under the trade names Rompun or AnaSed) is a veterinary sedative, routinely administered to large mammals, sometimes in conjunction with ketamine. It is also, as all of the above entities are noticing, increasingly filtering into the illicit supply of fentanyl, in which context it is sometimes referred to as “tranq” or collectively “tranq dope.”

Of course, fentanyl—and most street drugs—are cut with all sorts of things. What makes xylazine particularly alarming is its effects. The FDA decided not to approve its use in humans because of its “severe hypotension and central nervous system (CNS) depressant effects,” which is to say it puts people way out. As the Times put it, “it induces a blackout stupor for hours, rendering users vulnerable to rape and robbery.” Also, per DEA, “people who inject drug mixtures containing xylazine also can develop severe wounds, including necrosis—the rotting of human tissue—that may lead to amputation.” (I invite you to look up pictures if you want to learn more.) There’s a reason, then, it’s sometimes called a “zombie drug”—deep stupor plus rotting flesh is a new and particularly bad development in the already extremely bad drug crisis.

Sometimes such changes to the drug supply are flash-in-the-pan: it seems like synthetic cannabinoids didn’t scale like we once thought they might, e.g. That said, it’s already in 90 percent of the tested fentanyl in Philly, and spreading elsewhere rapidly. So it seems like there’s a real risk of xylazine becoming commonplace in the drug supply generally.

Here are four additional reactions to the situation:

We’re behind the curve on measuring xylazine’s spread

Xylazine use by humans is not actually that new. Chris Moraff, who does on-the-ground drug reporting in Philly, seems to have seen it there as far back as 2018. It seems, based on the surveillance data published last month in MMWR, like Philly is near the center of the crisis. (See also this paper.) On the other hand, it’s not the first place xylazine has shown up in the United States: as Moraff notes, people have been using xylazine in Puerto Rico for even longer.

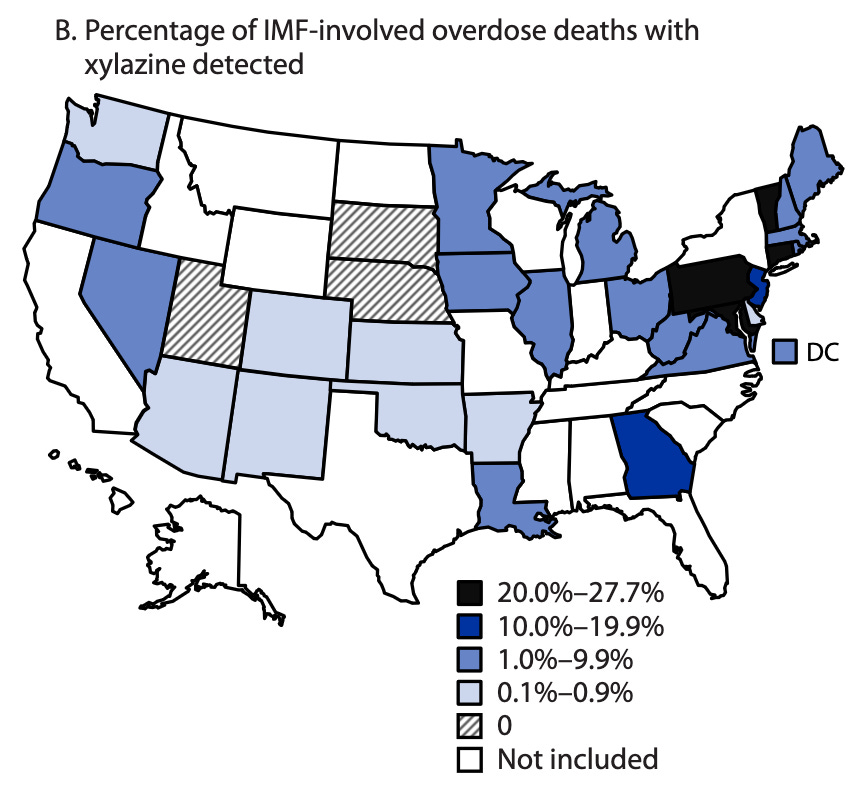

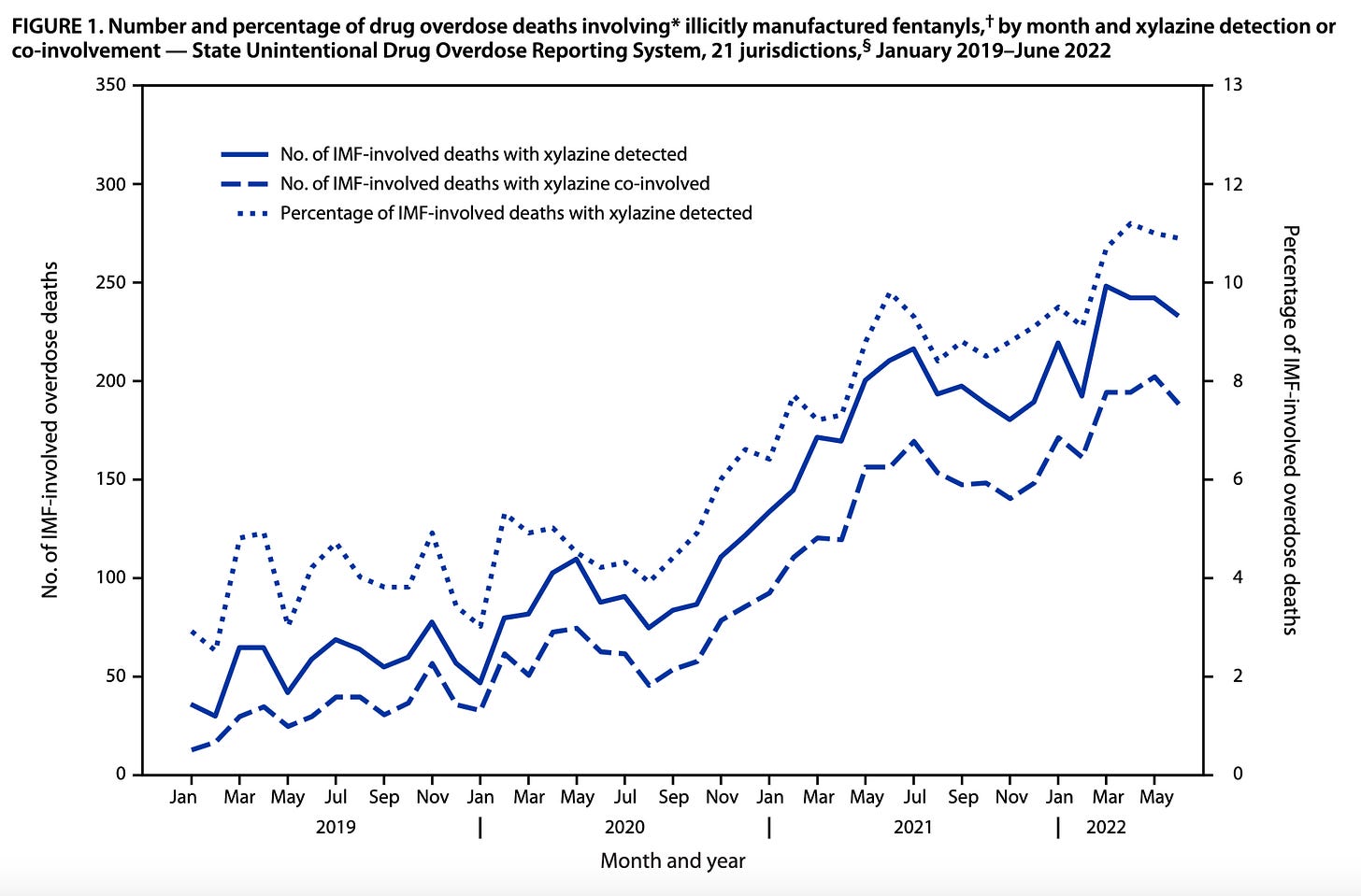

So we’re only picking up on xylazine’s spread now. But also, the public-facing data is only giving us a picture of how bad the problem used to be. The NVSS rapid release on xylazine adulteration, also released in late June, provides details on xylazine-involved ODs through the end of 2021. MMWR did a little better, giving us ODs through May of 2022.

But those data are still more than a year old. In other words, both the chart and the map above depict way out-of-date information about xylazine’s spread. The federal entities responsible for drugs—ONDCP, DEA, SAMHSA, etc.—hopefully have a more recent picture of the situation. On the other hand, it took until the end of 2022/beginning of 2023 for them to start making moves on the issue. So maybe not!

This is a general problem with drug policy—policymakers and the public are often flying blind, operating months or years behind reality. I can tell you how many COVID hospitalization happened last week in Mahnomen County, Minnesota (2), but not how many drug ODs happened there last year. Seems like a problem!

Xylazine is an improvement to product quality

A reasonable model of the fentanyl crisis is that it’s a change to the drug supply imposed on the market by producers, rather than demanded by consumers. As I discussed in National Affairs, fent. is just a massively better value proposition for the illicit market (as it is for the licit one!)—much cheaper, much easier to produce covertly, much easier to smuggle, etc. It provides such efficiencies that it was always going to outcompete heroin, even though consumers do not like the whole “much more likely to kill you” part of it.

It’s a little bit hard to say for sure why xylazine is spreading into the fentanyl supply. Some of it is its legal availability. Xylazine isn’t scheduled (as of May 2023) under the Controlled Substances Act. As a drug primarily administered to animals, it’s also relatively easy to get your hands on. (Moraff: “obtaining the drug requires only a veterinarian prescription, which is a piece of cake if you own a few horses, know someone who does, or just know which palms to grease.”)

But lots of things are widely available and uncontrolled, yet not making their way into the fentanyl supply. So what’s the value add of “tranq”? Here’s Filter’s1 Kastalia Medrano:

Xylazine is a Food and Drug Administration-approved veterinary tranquilizer, which in recent years has been increasingly cut into the illicit opioid supply in an attempt to make fentanyl a closer approximation of actual heroin.

Fentanyl on its own peaks fairly quickly, leaving many people with opioid tolerance facing withdrawal again two or three hours later. The effects of xylazine can last twice as long, and the right balance of the two can stretch out the fentanyl, i.e. “give it legs.”

Fentanyl is an inferior product to heroin in certain key ways, in particular the slope of its time vs. effect curve. The addition of xylazine helps flatten that curve. Of course, not everyone has the same preferences about their opioid use experience—Moraff reports interviews with people who like xylazine, and people who hate it. But what’s notable here is that xylazine is improving the quality of the product along its most important dimension, i.e. the quality of the high.

I raise this point because one common argument about the fentanyl crisis is that it is a product of prohibition’s constraint on consumer choice. In a truly free market in drugs, the argument goes, people would be able to choose to buy heroin, rather than being stuck with fent. And this may be the case! But it should be apparent that people also routinely choose drugs that cause serious, debilitating health effects, because it produces a better quality high in the short run. This is not necessarily irrational behavior, but it should remind us that drugs can and do cause people to make self-harming choices, independent of their legality.

Xylazine poses a problem for naloxone-forward policy

You know, naloxone: the opioid overdose reversing drug. Naloxone displaces opioids from opioid receptors in the brain. Xylazine is not an opioid. Naloxone has no effect on xylazine in OD!

In some senses, this is not unusual — we also don’t have overdose reversal medications for methamphetamine overdose, e.g. But because the lion’s share of the current crisis is driven by opioids (and fentanyl in particular), increasing naloxone access has become something of a compromise policy tool, a way to avoid having harder conversations about drug policy priorities. We can’t agree on if drug traffickers should be hanged or drugs decriminalized, if we need universal mandatory treatment or supervised consumption sites on every block. But you can get most people to agree that handing out an overdose-reversing drug is a good thing to do, so naloxone access laws have spread rapidly, we’re putting it in vending machines, etc.

This doesn’t mean that NALs or naloxone are bad, to be clear—my view is both that naloxone probably doesn’t reduce overdose in the long run, and also that if you have a tool for saving someone’s life in the moment, it’s morally mandatory to use it. But the spread of a non-opioid sedative into the fentanyl supply means that it becomes much harder to lean on naloxone as a consensus tool. You still want to use it! Fentanyl OD is still a problem. But much like with meth, xylazine means that your whole drug policy can’t be expanding naloxone access and hoping.

The best time to do something about xylazine was yesterday; the second best time is now

“The rich are different from you and me,” F. Scott Fitzgerald ostensibly once told Ernest Hemingway. “Yes,” Hemingway shot back, “they have more money.” As it is with wealth, so it is with drug markets: differences in size can mean qualitative differences in controllability. A market where a new drug hasn’t arrived yet, or where only a few dealers have it, poses a different enforcement problem from one where it’s the drug has already saturated.

This was the basic error that we made with fentanyl. Fentanyl used to be an east coast problem, basically unheard of on the west coast. Now it’s all over the west. Had we thought about markets where it was as different from markets where it wasn’t, we might have targeted resources in such a way as to stop the spread.

We have the opportunity to (attempt to) get this right with xylazine. Scheduling xylazine (the relevant bill is here2) under the CSA is a right first step. But that’s just leverage for the next step, which is to do differential enforcement in the (probably many) markets where xylazine is not yet common. What do I mean by differential enforcement? In essence, focusing enforcement resources on dealers who sell tranq-dope, and clearly communicating to those same dealers that cutting with xylazine will earn them special attention. Bryce Pardo and Peter Reuter proposed a similar strategy for fentanyl back in 2020:

Law enforcement should send an explicit message to dealers, informing them that they are responsible for keeping fentanyl out of the drug supply. They should be encouraged to acquire and freely use fentanyl test strips, returning to their supplier any purchase that contains fentanyl…. Meetings with market actors, such as dealers and regular users, may be part of the process to get the word out, but also to help study the unique dynamics of fentanyl procurement and supply…. There is a need to collect real-time information on the presence of illicitly manufactured fentanyl or other analogs using a variety of indicators: wastewater testing, routine drug monitoring purchases, drug seizures, drug residues on syringes, intelligence, or toxicology data from postmortems or emergency departments. When indicators suggest that fentanyl or some other analog has arrived, then the goal is to trace it to the specific dealer and the dealer’s supplier.

This is no longer a viable strategy for fentanyl in most places: the market has gotten too big and too entrenched. But it may be a viable strategy for keeping xylazine out. There are lots of benefits to that: it preserves the relative effectiveness of naloxone for OD reversal, reduces the healthcare costs associated with xylazine, and also reduces the suffering of the people using these drugs.

Do I think this is likely to work? Probably in some places! And more generally, the insight is that the best time to deal with an emerging crisis is when, or before, it’s emerging. if you wait, and drag your heels—as we already have—the problem gets too big to handle.

I take shots at Filter on Twitter a lot, on account of how they take big tobacco’s money to argue that drugs are good, actually. But I’ve got to give them credit: they often have on-the-ground details that others don’t, or before others do. So good on them!

Somewhat interestingly, the bill schedules xylazine only for illicit, i.e. in human or not in animal, uses (see Sec. 424). My understanding is that the goal is to preserve xylazine as an animal tranquilizer while controlling its use in humans—the fear is that producers will simply stop making it if it’s scheduled. I suppose my response to this is “who cares, get a new animal tranquilizer, you need to cut off supply.” But someone could convince me that this is not the correct balancing of costs and benefits.