What Was the War on Drugs? Part II

The Nixon Era

Previously: Introduction

The declaration of the War on Drugs is usually dated to an otherwise unremarkable press conference in June of 1971. President Richard Nixon, emerging from a two-hour meeting with advisors, did not actually use the phrase “war on drugs.” But he did tell the press that he was prepared to “wage a new, all-out offensive” against “America's public enemy number one”: drug abuse. Nixon promised a “worldwide” effort, and announced the formation of a new White House office responsible for coordinating drug policy across the federal government.1

Nixon, of course, did not invent drug-control policy. The first major federal drug-control law, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, was passed in 1914. Starting in 1930, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics waged an enforcement-focused campaign for almost four decades under the leadership of its infamous director, Harry Anslinger. Months before the press conference, Nixon had signed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, which created the substance scheduling system that remains the primary drug law of the land.

Nixon’s announcement, then, did not really inaugurate a transformation of drug policy per se. Rather, it changed its focus to the drug problem of the moment: heroin.

Heroin has been in America a long time. In the 19th and early 20th century, it was available over the counter. After prohibition, it remained popular in some milieus, especially the jazz clubs of the 1930s and 1940s.2 But the 1960s ushered in a full-blown heroin epidemic. In New York, the number of narcotic addicts doubled between the early 1960s and the early 1970s.3 In Atlanta and Boston, the number rose tenfold.4 In Philadelphia, the number of heroin overdose deaths rose from 5 per year prior to 1962 to 170 by 1970. “Jumping death rates,” one physician wrote in 1970, “are found from New England to Miami, Fla, from New Orleans to Seattle.” He further noted an alarming increase in youth use; heroin was then the leading cause of death in New Yorkers ages 15 to 35.5

Many were worried that the withdrawal from Vietnam would compound these problems. Heroin use had become widespread among GIs—a 1970 survey found that about 12 percent had tried it, and half of those were still using.6 As thousands of men returned home each month, one in twenty was found to have used heroin just before departure.7 An already simmering crisis might soon hit a boil as millions of vets returned still hooked on dope.8

Nixon’s War on Drugs, in other words, was not motivated purely by an irrational dislike of drugs. Nixon of course did hate drugs, especially marijuana, with a passion out of step with the consensus among elites, then and now. But his policy agenda was responsive to a real and substantial drug epidemic, one which merited a proportional government response.

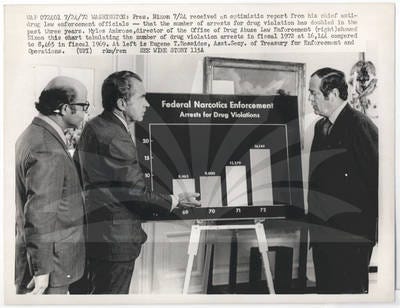

This response, furthermore, belied the now-popular view of Nixon as an all-enforcement drug warrior. Certainly, Nixon saw interdiction and policing as important components of policy, as communicated by both his rhetoric and, in 1973, by the establishment of the Drug Enforcement Agency. Federal narcotics arrests doubled, from about 8,000 to about 16,000, between 1969 and 1972.9 And Nixon also made drugs part of his international diplomatic efforts, for example in convincing the Turks to shut down opium poppy production in their country, which by 1971 was the principal source of roughly two-thirds of U.S.-consumed heroin.10

But, by comparison to what came before and after, the Nixon approach was a model of progressive drug policy. While he expanded enforcement spending, he also oversaw the repeal of most federal mandatory minimums for drug crimes.11 Nixon was also very clear that enforcement was not the only tool in his arsenal: “It has been a common oversimplification,” he told Congress in 1971, “to consider narcotics addiction, or drug abuse, to be a law enforcement problem alone.”12 Prior to the 1970s, federal drug policy had indeed focused entirely on enforcement. But Robert DuPont, who served as Nixon’s second drug advisor, has written that under Nixon enforcement was “augmented by an entirely new and massive commitment to prevention, intervention and treatment.”13

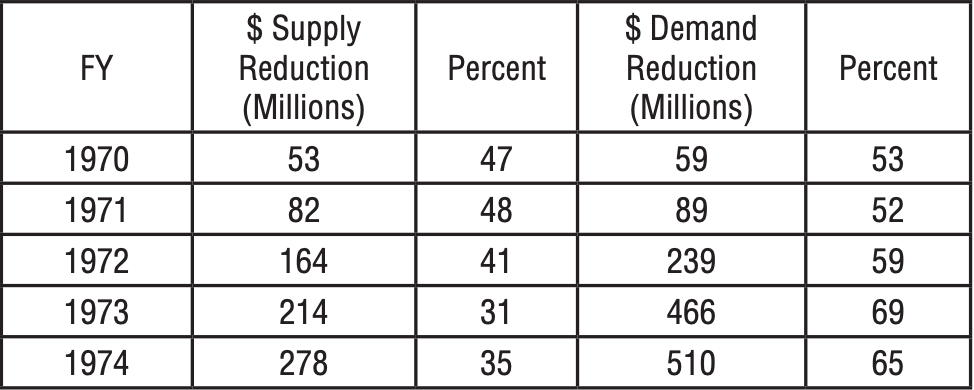

The numbers corroborate this claim. In 1970, the federal government spent nearly $60 million on “demand reduction”—treatment and prevention programming—compared to $53 million on “supply reduction” (interdiction and enforcement). By 1973, Nixon’s last full year in office, his administration was spending $466 million on demand, versus just $214 million on supply.14 With this money, the administration bragged of educating 440,000 students, teachers, and community leaders, and offering treatment to over 20,000 returning soldiers.15

This focus on demand was thanks not so much to a coherent theory of drug policy as to a remarkable new treatment for opioid addiction: methadone. Like heroin, methadone is an opioid. Unlike opium, it has a much lower potential to induce a high, especially when taken orally. In a landmark 1965 study, doctors Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander showed that methadone administered to heroin addicts relieved withdrawal without inducing a high. “With this medication, and a comprehensive program of rehabilitation, patients have shown marked improvement,” the pair wrote. “They have returned to school, obtained jobs, and have become reconciled with their families.”16

Methadone maintenance soon drew politicians’ attention. In 1965, Dole presented the idea to New York City’s hospital commissioner. By 1969, there were almost 2,000 New Yorkers enrolled in methadone maintenance programs; by 1970 there were 20,000. As New York enrollees showed major gains, programs were set up across at least 23 cities.17

One of the young men working in Dole’s lab was Dr. Jerome Jaffe—the same man whom Nixon would, in the infamous 1971 address, name to coordinate federal drug control policy. Thanks in large part to Jaffe, historian Jill Jonnes writes, “the Nixon administration was responsible for opening the first legal opiate clinics since the twenties.” By the end of Nixon’s administration, the nation had some eighty-thousand methadone program slots—enough to warrant the closure of the national drug treatment hospital at Lexington.18

Critics of Nixon’s War on Drugs, looking to link it to later efforts, often cite an interview with Nixon aide John Ehrlichman, who in 1994 allegedly told a journalist, “we knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. … Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”19 For opponents of the War on Drugs—and for the public that listens to those opponents—Ehrlichman’s confession is taken as final proof of what they have long suspected: Nixon’s drug policy was mostly a pretext to hurt black people and the left.

Usually left out is that Ehrlichman was such a liar that he was actually convicted of perjury in connection to Watergate, and that he held grudge against Nixon for—in Ehrlichman’s view—sucking him into the Watergate debacle that led to Ehrlichman’s imprisonment.20 A reliable source, he was not.

Beyond Ehrlichman’s credibility problems, even a passing review of the history suggests that we should identify Nixon’s drug war with the broader social reform agenda of the late 1960s. The phrase “War on Drugs,” after all, follows the same formulation as Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty” and “War on Crime.” All three were all-of-government efforts to eradicate social ills: the essence of liberal meliorism, not its antithesis.

It's not just that the standard story of the War on Drugs is wrong, nor that Nixon doesn’t deserve much of the criticism he receives. It’s that Nixon’s War on Drugs was an expression of the progressive ethos of that era, rather than a rejection of it. Nixon—the most conservative president between Hoover and Reagan—still prosecuted a drug control campaign that was fairly liberal by today’s standards.

Richard Nixon, “Remarks About an Intensified Program for Drug Abuse Prevention and Control” (Washington, D.C., June 17, 1971), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-about-intensified-program-for-drug-abuse-prevention-and-control.

Jill Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams: A History of America’s Romance with Illegal Drugs (London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 132–36.

Blanche Frank, “An Overview of Heroin Trends in New York City: Past, Present and Future,” Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 67, no. 5 & 6 (November 2000): 340–46.

James Q. Wilson, Thinking About Crime, Revised edition (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 6.

Joseph W. Spelman MD, “Heroin Addiction: The Epidemic of the 70’s,” Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal, November 1, 1970, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00039896.1970.10667300.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 272.

Lee N. Robins, Darlene H. Davis, and David N. Nurco, “How Permanent Was Vietnam Drug Addiction?,” American Journal of Public Health 64, no. 12_Suppl (December 1974): 38–43, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.64.12_Suppl.38.

Interestingly, this effect mostly didn’t materialize; most GIs returned home and got clean easily (see Lee N. Robins, “Vietnam veterans' rapid recovery from heroin addiction: a fluke or normal expectation?,” Addiction 88, no. 8 (August 1993): 1041–1054, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02123.x). Nonetheless, the preexisting user population, and their associated dysfunction, was enough to keep the problem in the public consciousness.

“Drug Arrests on the Rise in 1972” (UPI — The Nixon Presidency, July 24, 1972), 35160004354735, Chapman University Digital Commons, https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/upi_nixon/50.

John Berbers, “Nixon Says Turks Agree To Ban the Opium Poppy,” The New York Times, July 1, 1971, sec. Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/07/01/archives/nixon-says-turks-agree-to-ban-the-opium-poppy-turkey-will-ban-the.html.

Molly M. Gill, “Correcting Course: Lessons from the 1970 Repeal of Mandatory Minimums,” Federal Sentencing Reporter 21, no. 1 (2008): 55–67, https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2008.21.1.55.

Richard Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control” (Washington, D.C., June 17, 1971), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-drug-abuse-prevention-and-control.

Robert L. DuPont, “Global Commission on Drug Policy Offers Reckless, Vague Drug Legalization Proposal; Current Drug Policy Should Be Improved through Innovative Linkage of Prevention, Treatment and the Criminal Justice System” (Institute for Behavior and Health, October 26, 2011), https://web.archive.org/web/20120213081426/https://www.ibhinc.org/pdfs/IBHCommentaryonGlobalCommissionReport71211.pdf.

Michael F. Walther, “Insanity: Four Decades of U.S. Counterdrug Strategy,” Carlisle Papers, Strategic Studies Institute, December 2012, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA577164.pdf, p. 4.

“Fact Sheet: President Leads Fight Against Drug Abuse,” Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, accessed January 30, 2024, https://cdn.nixonlibrary.org/01/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/22122639/Nixon-Drug-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

Vincent P. Dole and Marie Nyswander, “A Medical Treatment for Diacetylmorphine (Heroin) Addiction: A Clinical Trial With Methadone Hydrochloride,” JAMA 193, no. 8 (August 23, 1965): 646–50, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1965.03090080008002.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 292.

Jonnes, 293.

Dan Baum, “Legalize It All: How to Win the War on Drugs,” Harper’s Magazine, April 2016, https://harpers.org/archive/2016/04/legalize-it-all/. I’m not saying that Baum made this quote up, but it is more than a little weird that he sat on it for over two decades before publishing it.

Lopez, “Was Nixon’s War on Drugs a Racially Motivated Crusade?”

I'm enjoying this series immensely and I wish a few parts were expanded or fleshed out just a bit. In today's post the section on Ehrlichman’s probably needs a bit more meat to it beyond "the guy was a liar". The words of people with credibility problems can still carry some weight.

A typical do-gooder idea that failed to reckon with the unintended consequences.