TRPP Laws: Targeted Regulation of Pornography Providers

Because prohibition and regulation are the same thing.

Many TCF readers have probably heard of TRAP laws. For those not in the know, “Targeted Regulations of Abortion Providers” are (as the name implies) health and safety regulations imposed specifically on abortion providers, almost exclusively with the intent of making the compliance burden too onerous to allow continued operation. Per the Guttmacher Institute, 24 states have some kind of TRAP law, including 14 states requiring abortion facilities to be structurally similar to surgical centers, and six requiring abortion providers to have admitting privileges at hospitals.

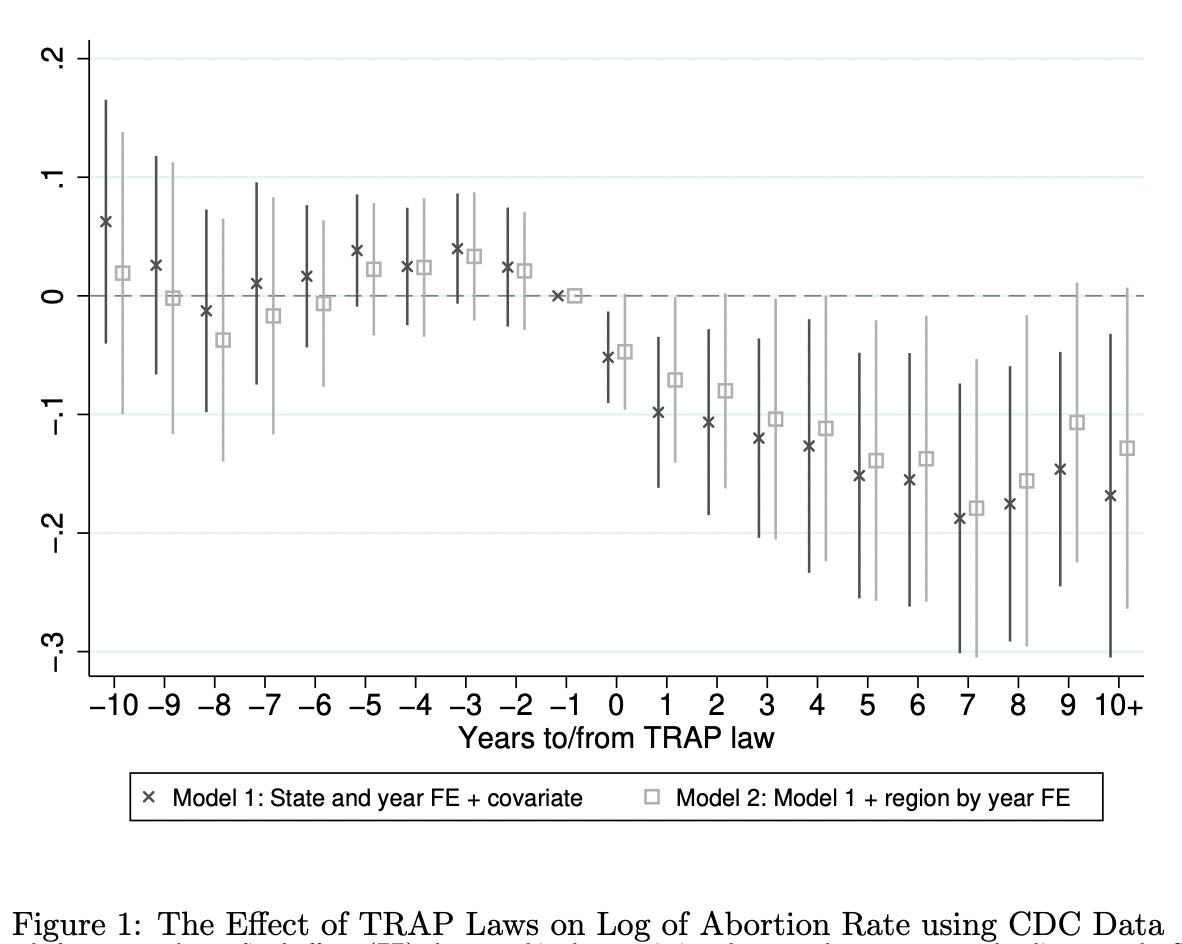

You may like or dislike these laws (that’s not really the subject of this post), but it is hard to argue that they don’t serve their intended purpose. A 2018 paper, Cunningham et al., looked at the effect of a TRAP law imposed in Texas in 2013. Its authors argue that the resultant clinic closures and increase in average distance to a clinic reduced abortion rates by 15 to 40 percent, depending on clinic distance. The above chart is from another paper, Arnold 2022, which looks at the average effects of the first TRAP law implemented in a state using a difference-in-difference specification. It finds the laws yield “a reduction in the abortion rate of approximately 5% the year the first law is implemented, and an average reduction of 11-14% in subsequent years.”

That TRAP laws reduce abortion should be unsurprising to TCF regulars. As you may remember, prohibition is a form of regulation. The obverse is true: regulation is a series of narrowly tailored prohibitions. As I wrote previously:

To reiterate, the more general form of this argument is that prohibition is a form of regulation. They are not distinct kinds of thing; one is a particularly aggressive instance of the other. Indeed, many kinds of regulation are simply targeted prohibitions. A hypothetical national potency cap is a prohibition on the sale of marijuana which exceeds the cap. A labeling requirement is a prohibition on the sale of marijuana which fails to comply with the requirement. Taxes on potency are a prohibition on the sale of untaxed product. The fact that some prohibitions are more or less targeted does not make them meaningfully distinct.

The same logic holds for abortion. An abortion ban (as exists in 12 states) is a prohibition on abortion. Like prohibition of other commercial services, it doesn’t reduce the level of abortion to 0, although it plausibly reduces it. Similarly, regulations of abortion are prohibitions on abortions that violate those regulations. TRAP laws prohibit non-compliant abortion providers, and therefore prohibit abortions provided by those providers. As a result, they reduce the total level of abortion in the equilibrium. I will reiterate (because this is a contentious topic) that one does not need to believe that this is good in order to believe that it is happening.1

If you are the sort of person who opposes abortion, though, then the utility of TRAP laws is that they shift the discourse. You no longer have to have a debate about the merits of prohibiting abortion (which, as of 2025, you are probably going to lose). Instead, you get to talk about health and safety standards in abortion facilities. You can point out that some facilities are probably below standards that sound reasonable (why shouldn’t abortion providers need to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals?), and you can use graphic stories about particularly poorly administered Planned Parenthoods (or whatever) to make your point. Moreover, because you have shifted the discourse to topics of health and safety, a large fraction of the public will simply tune out. Abortion is a hot-button social issue. Surgical facility standards are not.

With all this in mind, let’s talk about pornography.

As I observed over at The Dispatch recently, a great deal of pornography distribution is probably already illegal. That is to say, some substantial fraction of porn available online right now probably meets the Supreme Court’s extremely high Miller standard for “obscene” content. Obscene content is unprotected by the First Amendment and illegal to manufacture, distribute, or otherwise profit from under 18 USC Ch. 71 and a whole host of state laws. (Section 230 also doesn’t offer protection for platforms.) Consequently, I argue, the state has all the power it needs to, for example, shut down Pornhub.

I think the reason policymakers won’t do this is the polling—most Americans are opposed to banning pornography. That was true when I did this roundup of data on porn regulation for IFS six years ago (crazy how the time flies). And it remains true today. In the 2024 General Social Survey, fewer than 30 percent of respondents supported an all-out ban, compared to over two thirds who want it banned just for minors. We don’t like to say porn is morally acceptable, and we sure don’t like to admit to using it. But we also don’t want it banned.

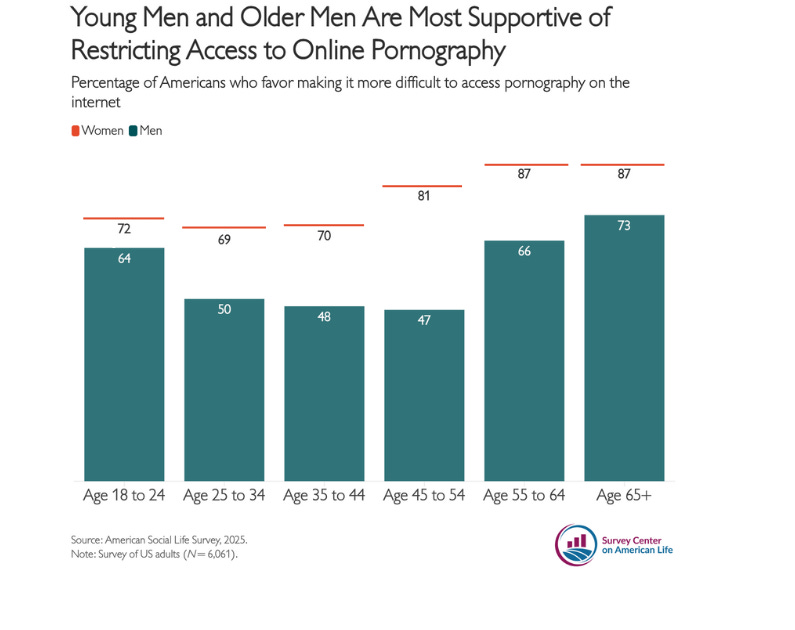

But, despite my protestations, we regard regulation and prohibition as distinct. And Americans do want pornography regulated. That was true in my IFS review. And it remains true in the polling from AEI/the Survey Center on American Life above, which finds that “[n]early seven in 10 (69 percent) Americans support making internet pornography less accessible, while fewer than one in three oppose such efforts.”

As with abortion, regulation of porn shifts the discourse. After all, banning sounds lame and square; regulation sounds reasonable and necessary. That’s particularly true of an industry that keeps facilitating the distribution of child sex abuse material, rape content, and revenge porn.2 How can people oppose reasonable regulations of the porn industry?

But of course, regulation is a form of prohibition. Imagine TRAP laws for porn—TRPP laws. These would be targeted regulations of pornographic content providers which are facially reasonable, but which impose substantial compliance costs that result in a reduction in availability of the product.

Actually, you don’t have to imagine. You can just look at North Carolina, where they’re currently trying to pass HB805 over an executive veto.3

HB805 does a number of things, including a bunch of gender-identity-related actions (these are probably why Governor Stein, a Democrat, vetoed). But in relevant part, it requires that online operators that publish or allow users to publish pornographic material verify that everyone appearing in that material “has provided explicit written consent for each act of sexual activity in which the individual engaged during the creation of the pornographic image”4 and “has provided explicit written consent for the distribution of the specific pornographic image.” It also includes rules about the consent forms, including requiring the presentation of a driver’s license or other identification. Failure to comply can result in a $10,000 fine per day of non-compliance; depicted people who did not provide consent can also bring civil suits.

I mean… this is a TRPP law. There are facially good reasons for these rules—it really is a huge problem if pornographic images of people are being distributed without their consent. And it’s reasonable to demand that distributors make sure that this isn’t happening. But also, there are billions and billions of porn “images” available online, many with totally anonymous participants. The compliance costs for a distributor like Pornhub are essentially impossible to meet. Pass the TRPP law, and the supply of porn will go down.

The big open question here is not popular support — I think you could impose similar laws in other red states — but constitutionality. Non-obscene pornography5 is protected speech, and the Court has repeatedly looked askance at the burdening of adult access to protected speech for other purposes. In legal terms, attempts to do so must survive “strict scrutiny,” the highest standard of Constitutional review, which says speech rights can be burdened only if the law is “narrowly tailored” to further a “compelling government interest” and uses the “least restrictive means” to achieve that interest. There are only two cases where the Court has blessed a restriction on speech under this standard (although they are notably both in the past 15 years.)

But there are signs that the Court might be shifting its posture on porn. In the recent ruling on age verification laws (Paxton v. Free Speech Coalition), the majority defined the problem in such a way as to be able to subject Texas’s verification law to a lower standard of review (intermediate scrutiny) which it successfully passed. Justice Elena Kagan, speaking for the three liberal justices, insisted that the Court should have used strict scrutiny … but implied that the laws might have passed muster anyway. That’s consistent with the view, going all the way back to the dissents in 2002’s Ashcroft, that the speech law made for obscenity in the 1970s might not be good for the technology of the then-future, now-present.

There is an analogy here, too, to TRAP laws. In 2016’s Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt, a relatively liberal Court struck down a Texas TRAP law. A similar result obtained four years later, in June Medical Services, LLC v. Russo. In that case, though, it was only because of Justice Roberts’s commitment to stare decisis, or deference to precedent. Roberts joined in the ruling with the four liberals, but reiterated his dissent from the decision in WWH. The other four conservative justices on the Court dissented in full. With the Court’s new 6-3 majority, one suspects that these precedents might be in danger of falling, too.

As with abortion restrictions, so with pornography restrictions—a new Court means a new political calculus. Claims of the “substantive due process death of obscenity law,” in other words, may have been premature. And now is the time for states to begin asking the Court tough questions about exactly how far they can go on the regulation of porn.

After all, unlike TRAP laws (which are divisive), the American public would like to see regulations of pornography. They are unlikely to be against consent requirements of the sort North Carolina is likely to impose. All that’s left, if the state actually passes its law, is for the Court to bless it; I am not certain, but I think there’s a real chance they will.

Please avoid the insufferable tic of assuming that the demand for goods you like is totally inelastic w/r/t policy, and the demand for goods you don’t like is totally elastic w/r/t policy. I talked about this here:

As I wrote in the Dispatch piece, “Pornhub has a demonstrated history of failing to self-police. The site used to make it easy to find videos of rape—many of them unsimulated—until a series of lawsuits and an investigation by the New York Times’s Nick Kristof, and still hasn’t really cleaned up its act. It’s also under a federal monitoring agreement related to its knowing distribution of content posted without participants’ consent.”

All credit to EPPC’s Clare Morell for drawing this law to my attention.

An “image,” per the statute, is “a visual depiction of actual or feigned sexual activity or an intimate visual depiction.” So it includes video.

“Isn’t all pornography obscene?” I explain this at length in the Dispatch piece, but the short answer is no. There’s a legal test of what qualifies as obscenity (the Miller test), which imposes a fairly high standard that not all pornography meets. Basically everyone agrees that sites like Pornhub contain at least some non-obscene but still sexual content.

Agree with this completely. To add a couple of suggestions:

1. It's as good a time as any to challenge Miller and whatever other Warren/early Burger Court caselaw is cited as a reason that porn can't be banned or restricted, although of course it should be done carefully.

The average year of birth of the Court that decided Miller was 1910; to put that in perspective, they would have been 43 and 55, respectively, when Playboy and Penthouse were launched. They were raised in an America that generally protected them from smut and unfortunately didn't appreciate it.

The current court's average year of birth is 1960, and several of the younger members likely first used the internet in their 20s, putting them in a much better position to appreciate its dangers.

2. States ought to allow for private enforcement of their pornography regulations. It's one thing to have an attorney general who might not prioritize targeting a porn site owner for distributing to minors; it's a whole different thing if parents and/or nonprofit law firms can take the site's owner to court and collect a judgment. The latter can be expected to be much more enthusiastic in this role.