Yes Of Course You Can Regulate Porn

On several bad arguments against vice control

Politico has a story today about a remarkable state policy success story. A handful of state legislatures have been strengthening age verification requirements for porn sites. The bills are bipartisan affairs, joining right-wing moral majority types with left-wing feminists. What is more, they appear to be working!

Lawsuits have been filed by the porn industry’s trade association, the Free Speech Coalition, against Utah and Louisiana, but in the meantime, porn companies have had no choice but to comply with the laws. According to Ethical Capital Partners, the private equity company that owns Pornhub, traffic in Louisiana has dropped 80 percent. [By the way, how absurd are these industry group names?]

In the other three states where the laws have been in effect for months — Utah, Mississippi, and Virginia — Pornhub did something even more unprecedented: It simply stopped operating. Users in these states who attempt to visit the site are greeted with a safe-for-work video of Cherie DeVille (a porn star), clothed, explaining the site’s decision to pull out of the state. [Two more states, Texas and Montana, have passed laws that are not yet in effect.]…

As Stabile explained, age-verification laws make traffic to porn sites drop precipitously. It turns out, unsurprisingly, that nobody wants to upload their driver’s license or passport before watching porn. And, as Stabile added, at a cost to the operators of around 65 cents per verification, age verification is effectively “business-killing.”

As I wrote a few years back for the Institute for Family Studies, there isn’t really a constituency for banning pornography. But there is one for far more aggressively regulating it. Americans consistently report that they think porn is immoral, and generally think it should be inaccessible to children. You can also mobilize support by pointing out that the market is dominated by a monopolist, that that monopolist does a poor job filtering out illegal content, and that performers are frequently abused!

So in my view “reasonable regulation of pornography” is a winning political position with bipartisan popularity which, as a side benefit, would probably substantially reduce its availability and therefore its pervasive health and cultural harms. Politico’s reporting seems to bear out that view. Bully for me.

But that’s not why I wanted to write a post. I wanted to write a post because upon reading this article I immediately Imagined a Type of Guy, a type of guy who would contrive a reason to oppose this sort of regulation not on principled grounds, but because it is ostensibly self-defeating, or even dangerous. And, unlike most imagined types of guy, this guy is real! Here’s Julian Sanchez, formerly of the Cato Institute, responding to the article:

Well gosh, now I’m sure nobody in those states will be able to find pornography online.

The best case scenario here is that people just use VPNs and the laws have no real impact. The uglier scenario is that people shift to smaller sites that don’t care about complying with U.S. laws & don’t police their content to the same extent.

I want to talk about this argument because it’s a standard line of opponents of vice regulation—porn, drugs, and all the rest. And thinking about why it’s wrong tells us something about what vice control, and especially prohibition, isn’t, and what it is.

Of course, we’re not really talking about prohibition here. We’re talking about regulation—regulation which, to be clear, is simply requiring porn sites to comply substantively with the expectation that porn won’t be distributed to minors! Porn is still very much legal to produce, distribute, and consume.

But you can think about such regulations as a point along a spectrum of availability of a good. On one end is, say, full prohibition with aggressive enforcement—porn is illegal and anyone who thinks a dirty thought is shot in the street, no trial. On the other end is full legalization, or perhaps subsidy—Universal Basic Porn. Obviously no one embraces either extreme; the point is that at an abstract level, de/regulation exists on a single dimension of availability/suppression.

This holds true for any good, vicious or otherwise. Milk is heavily regulated in the United States, at both the state and federal level. This was not always the case. Proponents of its regulation see it as one of the great health and safety regulations of the early 20th century, while opponents see it as an intolerable impingement on the freedom to, uh, get Listeria.1

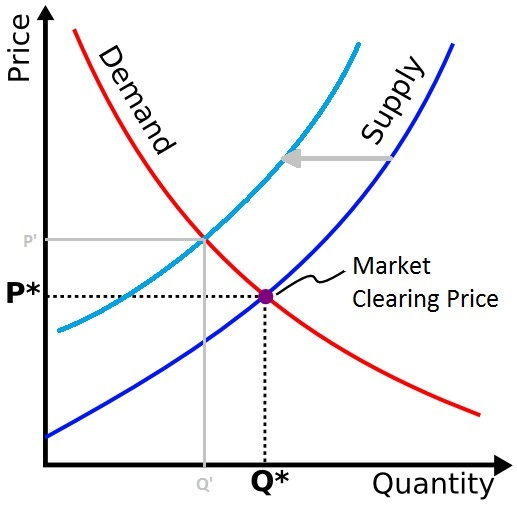

What almost everyone should be able to agree on is that the cost of regulations ends up reflected in the final price and quantity produced and consumed. The figure above is from an article about the effects of regulation on the health-insurance market, but the principle holds generally. The imposition of a regulation shifts the supply curve left, e.g. by excluding from the market those milk suppliers unwilling or unable to comply with health and safety requirements. If the demand curve remains constant, then the quantity supplied falls and the price rises.

Actually, the story is slightly more complicated than this, because regulation can also affect demand. Age verification is a perfect example: not only does it impose costs on the distributors of porn, it also filters out users who cannot prove (truthfully or otherwise) that they are over 18, thus reducing total demand for the product relative to the counterfactual. Drivers’ licenses similarly limit demand for cars. We could imagine a milk drinkers’ license, which would limit demand for milk.

Prohibition—of porn, of drugs, or of raw milk—is just an extreme version of this dynamic. In the real world, it works through a number of mechanisms:

It is harder to produce illegal substances. Prohibition increases the opportunity cost of engaging in illegal activity, because the rewards are lesser, meaning there will be less willingness to provide the goods and services that are a predicate to that activity. In the case of pornography, for example, more aggressive regulation reduces the opportunity-cost of participating in its production. Prohibition redoubles it—being a porn producer or actor becomes far less attractive as a vocation when control drives down your earnings relative to other jobs!

It is harder to find illegal substances. One of effects prohibition has on demand is to increase the search time for obtaining the desired illegal substance. If it takes you three minutes to find heroin or porn, you’re more likely to consume it more often than if it takes you three hours. That time cost is reflected in demand.

It is harder to engage in transactions related to an illegal substance. A major limit to the scaling of legal weed, for example, is that it remains federally illegal, such that entities that operate interstate—including most banks—will not do business with marijuana sellers. Business in a fully illegal substance (e.g. heroin) often requires elaborate illegal financial structures to operate at scale, the costs of operating which are then passed on to consumers in terms of higher prices.

Many people like following laws. Not everyone, of course. But all else equal, if something is prohibited, fewer people will consume it out of a sense that it is good or necessary to follow the law. Even people who do not like following laws will do so because they fear the consequences of not doing so.

Regulation, and prohibition by extension, reduce the supply and increase the cost of a good or service. This is bad in the case of things that are good. Deregulating housing, energy, education, or any of a number of other over-regulated goods would be steps in the right direction! But it is good in the case of things that are bad: imposing additional cost on vicious goods reduces their availability and increases their price. And that is good insofar as those goods hurt their consumers, the people around them, and society at large.

Which brings me back to Sanchez, and all the people for whom I am using him as a stand-in. Sanchez’s tweets can be read as making three arguments: that prohibition does not reduce supply to zero; that people will susbtitute to another source of porngraphy; and that that substitution may entail choosing a more, rather than less, harmful form of porn. All of these arguments are in the context of regulation, but because prohibition is just regulation of far greater degree, they are all often applied to prohibtion per se.

Sanchez’s argument 1 is the sarcastic “Well gosh, now I’m sure nobody in those states will be able to find pornography online.” This is a standard libertarian strawman: prohibition or regulation is taken to have as its purpose the reduction of supply of the targeted good to zero; supply is obviously not going to be reduced to zero; therefore, prohibition is a failure. Pressed on this, I am sure Sanchez would deny that this is his view. Yet this argument is made all the time in the context of drug control: in spite of prohibition, people still use drugs, therefore prohibition does not work.

What this view—implicit or explicit—misses is the people who do not use the regulated substance, or use it less, because of the added cost and reduced quantity associated with regulation/prohibition. In the case of drug prohibition, that means the millions of people who do not consume heroin because it is not available to them in a licit market, and the thousands more who consume it less than they would otherwise because of the costs imposed by prohibition. In the case of pornography regulation, the imposition of even a very small regulatory cost apparently does substantially reduce the supply of porn—pornhub traffic is down 80% in Louisana!—and therefore probably at least marginally reduces its consumption. Most critically, it reduces its consumption among the population—those under 18—to whom regulators most want to reduce availability.

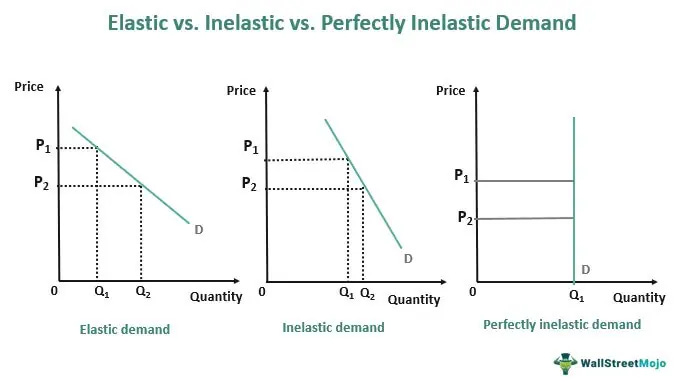

This brings us to argument 2, i.e. “The best case scenario here is that people just use VPNs and the laws have no real impact.” There are two things wrong here. One is the internal contradiction. People being forced to use VPNs to access porn is a real impact. It imposes a barrier to entry, one that not everyone knows how to get over—some people know how to use VPNs, but many do not. More generally (second thing) the assumption is that the quantity of the regulated substance consumed will be constant without regards to regulation. The implication here is that demand for pornography is perfectly inelastic (see the charts above). Regardless of how you shift the supply curve, users will consume the same quantity of porn, totally unaware of price.

But there’s no reason to believe this is true. The demand for heroin isn’t perfectly inelastic. The demand for porn certainly isn't! Again, a similar argument is often used against drug prohibition: people will always consume drugs, no matter the level of regulation. But the demand for drugs isn’t perfectly inelastic: even people with severe addictions respond to increases in price with reductions in consumption. And even goods that are inelastic in the short run are elastic in the long run, as illustrated every time someone insulates their house or buys a more fuel efficient car because energy prices are high. Similarly, consumers of a vicious good may adapt their consumption over the long run in light of a persistent change in the regulatory regime, even if there are no short-run changes.

Of course, Sanchez’s point is also that people will internalize the cost—they will consume porn + VPN rather than porn. But of course, porn consumption is heterogenous: some people will substitute, some people won’t. Some people will reduce their consumption a little bit, some people won’t. Invoking the specter of the latter does not diminish the impact on the former. And who will be affected matters: even if chronic adult porn consumers will not much change their behavior, some children who would have used porn enough to get hooked on it will now find doing so too difficult and never develop the habit.

This is why argument 3, a variation on the iron law of prohibition, is important for the anti-control position. Sanchez writes that “the uglier scenario is that people shift to smaller sites that don’t care about complying with U.S. laws & don’t police their content to the same extent.” Substitution may mean substituting to more harmful forms of the consumed substance, the thinking goes. Better not to force the substitution at all!

There are two arguments against this view. One is that even if regulation/prohibition increase the intensity of consumption, they also reduce its extent. There’s an optimization point here, of course, but I don’t think it’s obvious that we’re at the optimal balance in a market where 3 in 4 teens have consumed pornography.

The second is that substitution to smaller distributors is not necessarily bad. Thanks to generous interpretation of the First Amendment, the American pornography industry is possibly the world’s most prolific, generating $10 to $12 billion in revenue every year. Unchecked by regulation, big porn maximizes revenue by delivering increasingly extreme content to its users, particularly the subset who are most addicted to their products. (How else does an industry whose products are constantly stolen make money?) Forcing substitution to less sophisticated operations could lead to consumption of a shadier product. But it could also mean users are getting a qualitatively less potent experience, which would be better. I am actually agnostic as to which outcome is more likely—probably it’s both, depending on the consumer!—but I don’t think there’s a reason to prefer Sanchez’s theory to mine.

I’ve spent a lot of time using Sanchez as an example, but I want to make a more general point now, so let’s set him aside such that I don’t cast aspersions on him specifically. In general, it is remarkable to me when libertarians make arguments like the foregoing. It is remarkable because often such people in other contexts recognize the real harms that regulation impose on the operation of a free market in desirable goods and services. I agree with them, in fact, that many products should be dramatically less regulated, indeed should be barely regulated or altogether unregulated. But when it comes to vices, they suddenly lose the ability to do the analysis they would for housing or hair-braiding. They refuse to recognize that regulation can create inefficiencies in the market—inefficienies that are, in the case of vices, socially and individually beneficial.

On some level I suspect (without, again, casting aspersions on Sanchez or any other individual) that these prudential objections are ultimately pretextual. Maybe the people making these arguments just like porn! (Which, I mean, many people like looking at pictures or videos of naked people having sex. That’s not an insane position, just a socially undesirable one.) Or maybe it offends their principled belief in privacy or free expression (I don’t really think either is infringed upon by keeping hardcore porn away from children, but I’m old-fashioned like that.)

But, as with so many other arguments, they avoid making these principled arguments because they know their principles are unpopular and offensive. I, meanwhile, get to take stances like “it’s good when it’s harder for kids to get porn.” It’s nice to defend things everyone agrees with.

Just joking, raw milk people.

Great essay, thank you

i completely agree in the case of drug possession, but i think the internet is unique in that it is a worldwide system and it is impossible to meaningfully regulate or ban things at a nationwide level. making drugs "more difficult" for me to access has already happened; i would have no idea where to look for them. For me to find pretty much anything on the internet is trivial, no matter how obscure, how banned, how illegal, and how universally illegal it is. Just look at how easy it is to find pirated movies or (in Germany) anything offically illegal in Germany such as Nazi memorabilia on the Internet. There is also the streisand effect and the fact that the predictable response to universal illegality of porn is everyone simply spamming porn on any site where you might be able to upload content to make it impossible to hide all porn. It is genuinely impossible to ban things on the internet without basically becoming china, in a way that is not true of physical items.