What Was the War on Drugs? Part III

The Parents Movement

Previously: The Nixon Era

In 1979, the federal government conducted a survey of Americans’ drug use habits. They asked, among other things, about when respondents had first tried drugs. The results were quite startling. Rates of drug initiation, the responses imply, were quite low prior to 1960. Only about 2.4 million Americans alive in 1979 first tried any of the major illegal drugs (marijuana, cocaine, heroin, or hallucinogens) in 1960 or before. But 1.8 million tried drugs in the years 1961 to 1964—almost as many as the preceding several decades. The number grows from there. Between 1965 and 1968, 7.8 million first tried drugs; 1969 to 1972, 16.5 million; and 1973 to 1976, 17.8 million. As many as 5 million people probably tried drugs for the first time in each of 1977 and 1978.1

An analysis of retrospective data like this is necessarily imperfect.2 Nonetheless, it corroborates the widely held belief that in the 1960s and 1970s, many more Americans started doing many more drugs. That increase in drug use, furthermore, reflected increasing social comfort with the use of drugs. Thus one of the problems with assuming a continuous drug war from Nixon to Reagan: through much of the 1970s, policymakers and culture declared a ceasefire.

For decades, drugs were shunned. But in the 1970s, they were suddenly everywhere. Whether it was the Beatles’ psychedelia or marijuana songs like Brewer & Shipley’s “One Toke Over the Line,” drugs were all over the radio. Pot-themed publications sprang up. High Times, the most famous, at one point sold over 400,000 copies a month, and had a 100-person staff.3 By 1978, the New York Times was breathlessly reporting on head shops that sold paraphernalia made for kids, like “a baby bottle fitted with both a nipple and a hashish pipe and a felt-tipped pen that allows a surreptitious snort of cocaine.”4

The cultural interest went beyond pot. While the heroin epidemic was still visible enough to make it unattractive, cocaine was rapidly gaining popularity. A 1971 article in Newsweek—circulation 2.6 million and rising5—called cocaine “the status symbol of the American middle-class pothead,” mentioned the fashion of wearing a spoon around the neck, and included a “co-ed” claiming that “orgasms go better with coke.” The following year, glowing coverage in Rolling Stone blamed cocaine’s prohibition on “absurd laws about harmless drugs.”6

Cultural change begat political activism. Pro-liberalization groups popped up throughout the country—marijuana historian Emily Dufton7 identifies not just major groups like the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) but local outfits like Atlanta’s Committee Against Marijuana Prohibition (CAMP) or Beloit College’s Student Association for the Study of Hallucinogens (STASH).8 These activists moved public opinion on marijuana: support for legalization rose from 12 percent in 1969 to a peak of 28 percent in 1977, a remarkable shift in public opinion in such a short time.9

Even more remarkably, policymakers actually listened to them. Between 1973 and 1978, a dozen states, collectively home to more than a third of the population, passed laws removing criminal penalties for possession of up to an ounce of marijuana.10 When Jimmy Carter became President, he made his chief drug policy advisor Dr. Peter Bourne, a physician who had once called cocaine “probably the most benign of illicit drugs currently in widespread use” and argued that the case for cocaine legalization was at least as strong as that for marijuana.11 Under the influence of both Bourne and NORML’s Keith Stroup, Carter endorsed marijuana decriminalization nationwide in 1977.12

That, of course, did not come to pass. And Bourne eventually resigned after it was reported that he had written a prescription for quaaludes for an aide under a false name and snorted a line of coke at a NORML party.13 But the fact that the Carter White House embraced marijuana decriminalization shows that the “War on Drugs” was not a continuous campaign, but fought in stops and starts for its first decade. More to the point, it shows the ways in which drugs and drug use became more normal in the ‘70s: from the magazines to the campuses to the White House, millions of Americans were saying yes to drugs.

Which is exactly what had Keith Schuchard so worried.

Marsha “Keith” Mannat Schuchard was an unlikely leader of an anti-drug movement. She was a liberal Democrat, not a fire-breathing conservative. She had tried pot while she and her husband were studying for their PhDs in literature. But that didn’t stop Schuchard’s surprise one warm August evening, just after her eldest daughter’s birthday party. The party, Schuchard reported, had been odd, the attendees—mostly seventh and eighth graders—“bleary-eyed” and “incoherent.” When she and her husband surveyed the results of the party, they found “marijuana butts, plastic bags with dope remnants, homemade roach clips, cans of malt liquor, and pop wine bottles” strewn across the lawn.14

Schuchard reached out to the parents of the party’s attendees. From those conversations came a meeting, at which attendees expressed how out of control they felt their kids’ drug use had become. They formed a group—their kids derisively labeled it the “Nosy Parents Association”—to work together to discourage drug use.15

What started as a suburban parents’ association soon became a movement. With the aid of Robert DuPont, the Nixon drug advisor, and Georgia State health professor Buddy Gleaton, Schuchard created the Parents’ Resource Institute for Drug Education, or PRIDE. By 1979, PRIDE had a nationally circulating newsletter. By 1980, Dufton writes, “there were hundreds of Schuchard-inspired groups across the country, calling themselves Parents Who Care, Parents Alert, United Parents of America and a host of other names.”16 Sue Rusche, another early Parent Movement leader, said that within the first few years of the movement there were some 3,000 groups nationwide.

“There was just this explosion of anger, on the part of parents that were living then and raising kids,” Rusche said. Parents were asking “how can this be happening in my community? And I'm gonna make it stop.”17

Parents’ concerns went beyond illegal drugs. On May 3, 1980, 13-year-old Cari Lightner was struck and killed by a drunk driver. Police later told Cari’s mother, Candy, that the man who had killed her daughter had three prior drunk driving arrests. Outraged, Candy joined together with some friends to launch MADD: Mothers Against Drunk Driving. In the next decade, thanks largely to MADD’s advocacy, states would pass hundreds of drunk-driving laws.18

It wasn’t just white, middle-class parents like Schuchard who were worried about drugs in their communities. Black parents, too, were speaking out. In New York, Harlem’s black community leaders had already rallied a “black silent majority” around support for Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s punitive drug-law reforms.19 Detroit’s first black Mayor, Coleman Young, “brought the majority-black audience of more than two thousand people to its feet” by declaring that “I issue an open warning right now to all dope pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers: it’s time to leave Detroit.”20 And in Washington, D.C., it was black leaders who led the fight against marijuana decriminalization, as a majority of black residents opposed it against a white majority that supported it.21

The Parents Movement, as it would come to be called, transformed the conversation around drug use. They did so, Dufton argues, by changing the locus of concern from the rights of adults—the right to consume drugs, especially marijuana, without government interference—to the needs of children.22 The emergence of MADD, with its emphasis on mothers’ outrage, reflects the same tendency: a sense that substance use imperils children, and the rights of adults should be curtailed to reduce that risk.

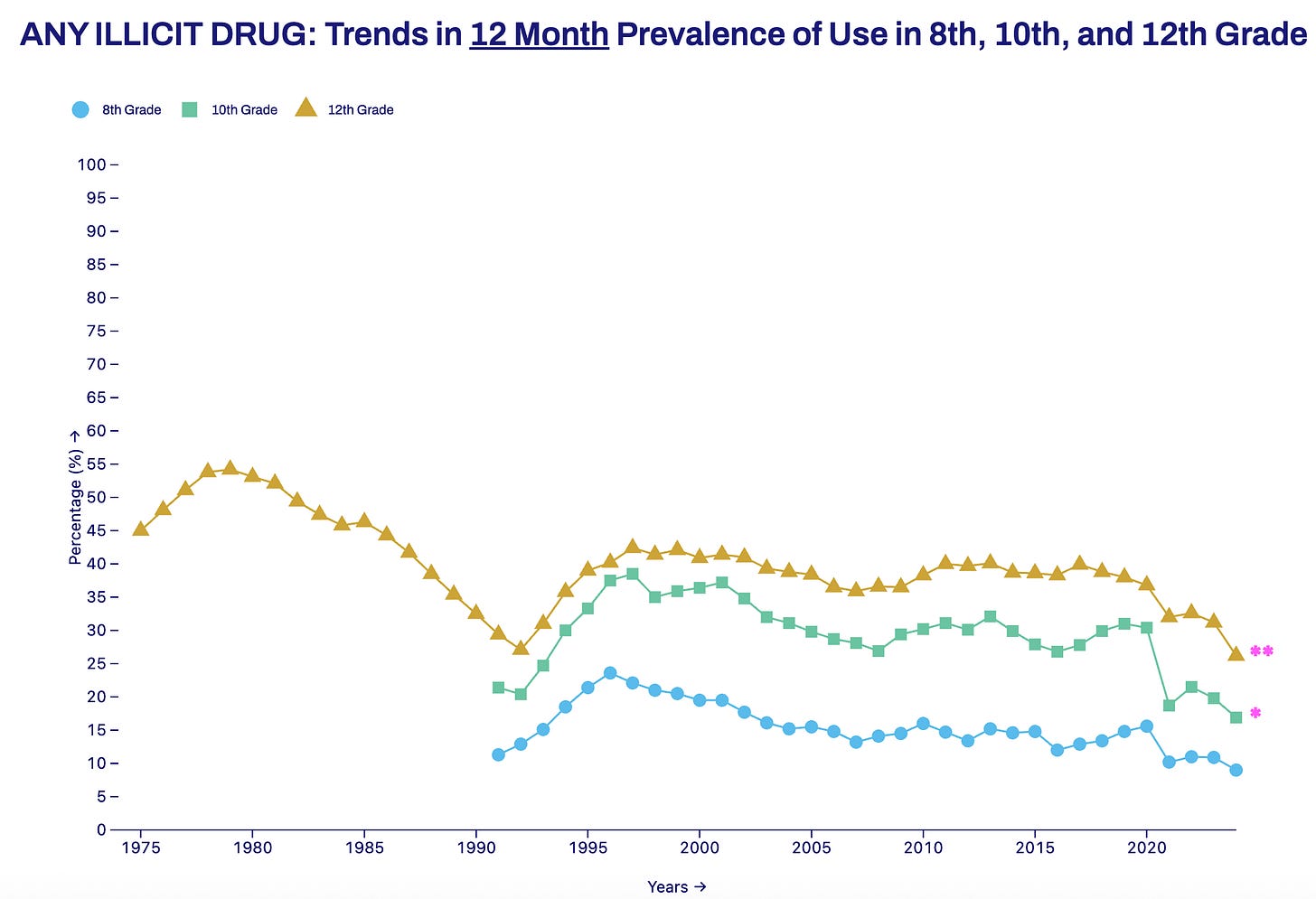

It might seem easy to see parents like Schuchard as unhip moms and dads who were freaking out over nothing. But the reality is that, by the time they started noticing, teen drug use was a large and growing problem in America. In 1976—the first year the government asked—48 percent of graduating seniors reported using any illicit drug in the past year. That figure would peak at 54 percent in 1979. Many of these were “just” smoking marijuana. But fully a quarter of seniors reported using illicit drugs other than marijuana in 1976, and more than a third in 1981.23

To be sure, lots of kids experiment with drugs. For many, those experiences are fine, even pleasant. But many also get hurt. A teen who smokes and drives can die in a car crash, or oversleep and misses a crucial test. Or they can get addicted, leading at least to debilitating symptoms, and in many cases to ongoing mental health problems—a particular risk in exposing the developing teenage brain to drugs. One does not have to be a breathless square to recognize that it's not good for kids to do drugs, and it’s not good for a culture to glamorize drug use if it means kids getting high.

More to the point, understanding the War on Drugs means understanding that, by the late 1970s, American culture really was glamorizing drug use, often to harmful effect. The history of the parent movement—rarely mentioned in contemporary polemics against the Drug War—captures how the 1980s backlash against drugs was the result of a grassroots movement, grounded in a legitimate concern about real and substantial problems.

In fact, without the parent movement, it’s hard to say if there would have been a renewed War on Drugs at all. Because by 1980, a champion of the movement was about to enter the White House.

Parent movement groups “were warmly received by the Reagan administration,” drug historian David Musto writes.24 In particular, the movement found a close ally in First Lady Nancy Reagan. Even before she was in the White House, Mrs. Reagan worked closely with movement leaders.25 The relationship persisted when her husband entered office, as Mrs. Reagan drew staff from the National Family Partnership, a parent movement umbrella organization. 40 NFP members were present, too, at a November 1981 meeting at which the first lady announced she would focus her time in the White House on preventing adolescent drug abuse.26

That campaign eventually begat Mrs. Reagan’s now-famous slogan, “Just Say No.” The phrase, she claimed, came from a meeting with a group of children in Oakland, California. “I was asked,” the first lady recalled in 1986, “what to do if they were offered drugs. And I answered, ‘just say no.’”27

“Just Say No” today is often recalled with derision, an almost hopelessly naïve slogan for a more foolish time. But that unflattering image belies Mrs. Reagan’s legacy as a prevention activist, an extension of the parent movement. By the end of Reagan’s second term, the first lady’s work had led to the founding of over 12,000 “Just Say No” clubs and gotten more than five million people to attend Just Say No marches in 700 cities.28 “Just Say No” may have been a joke to some, but to others it was a serious slogan for those fed up with drugs.

Author’s analysis of NHSDA 1979 data, available at https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-household-survey-drug-abuse-1979-nhsda-1979-ds0001.

People who use drugs are likely to engage in other risky behaviors, such that those who use drugs less recently are more likely to be selected out of the survey due to death; people tend to be less able to recall events that happened less recently, which reduces the precision of earlier estimates; etc.

Emily Dufton, Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America, First Edition (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 77.

Emily Dufton, “Just Say Know: How the Parent Movement Shaped America’s Modern War on Drugs, 1970-2000” (Dissertation, George Washington University, 2014), 45, https://scholarspace.library.gwu.edu/concern/gw_etds/nv935299n?locale=de.

Henry Raymont, “Newsweek, With Elliott Editor Again, Enters Period of Drastic Reappraisal,” The New York Times, July 11, 1972, sec. Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/07/11/archives/newsweek-with-elliott-editor-again-enters-period-of-drastic.html.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 304.

Much of the first half of this section is based on Dufton’s research, including her doctoral thesis, cited below.

Dufton, Grass Roots, 31–32.

Lydia Saad, “Grassroots Support for Legalizing Marijuana Hits Record 70%,” Gallup, November 8, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/514007/grassroots-support-legalizing-marijuana-hits-record.aspx.

Dufton, “Just Say Know,” 39–40.

David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control, 3rd edition (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999), 259.

Dufton, Grass Roots, 84.

Musto, The American Disease, 262–63.

Dufton, “Just Say Know,” 49–51.

Dufton, 51–52.

Dufton, 58–62.

Sue Rusche, interview by Charles Fain Lehman, January 31, 2024.

James C. Fell and Robert B. Voas, “Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD): The First 25 Years,” Traffic Injury Prevention 7, no. 3 (September 1, 2006): 195–212, https://doi.org/10.1080/15389580600727705.

Michael Javen Fortner, Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment, 1st edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: Harvard University Press, 2015).

James L. Forman, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017), 31.

Forman, 17–46.

Dufton, “Just Say Know,” 81.

https://monitoringthefuture.org/about/

Musto, The American Disease, 266.

Sue Rusche, interview.

Dufton, “Just Say Know,” 109–11.

CNN: 1986: Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” Campaign, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQXgVM30mIY

Tessa Stuart, “Pop-Culture Legacy of Nancy Reagan’s ‘Just Say No’ Campaign,” Rolling Stone, March 7, 2016, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/pop-culture-legacy-of-nancy-reagans-just-say-no-campaign-224749/.

Fascinating is the difference between MADD and the various other anti-drug movements. MADD won in the state legislatures, but MADD+prohibitions+enforcement also won a culture war. Autonomous police and prosecution enforcement rose, opinion turned against inebriated drivers, local ordinances sprang up everywhere regulating (for example) service in bars, and the need for a 'designated driver' no longer required explanation. At various times (Pandemic excluded) it has looked like alcohol consumption generally has been in decline. Elsewhere, smoking is a domain where public education, taxation, and regulation required only a bit of enforcement to engender similar cultural shifts. Other culture-changers should take note!

I like this series a lot. I’m a pretty libertine guy concerning drugs, generally speaking, but I’ve never heard the case against them stated so eloquently and empirically. Thanks.