What Was the War on Drugs? Part IV

The Reagan Era

Previously: The Parents Movement

While Nancy Reagan was a committed drug warrior from the start, her husband took longer to put together a coherent strategy. That is not to say Ronald Reagan didn’t think about drugs, or wasn’t tough on them. At his second presidential news conference, when asked about “growing concern about the drug abuse problem,” Reagan called it “one of the gravest problems facing us internally in the United States.” But Reagan also seemed skeptical of drug interdiction, saying that “it’s like carrying water in a sieve.”

Rather, Reagan said, “it is my belief, firm belief, that the answer to the drug problem comes through winning over the users to the point that we take the customers away from the drugs, not take the drugs, necessarily … You don't let up on that. But it's far more effective if you take the customers away than if you try to take the drugs away from those who want to be customers.”1

Such demand-focused language sounds more like Kerlikowske than it does the popular conception of Reagan. And indeed, the focus on demand over supply would not last. By the time Reagan left office, the federal government was spending $4.5 billion annually on drug supply control efforts. That represented a three-fold increase, inflation-adjusted, over his first year. It was also more than double the $2.1 billion the federal government spent on demand reduction, a budget category essentially stagnant in inflation-adjusted terms until 1987.2 More money was paired with more action. Drug arrests reported to the FBI rose from about 500,000 in 1981 to over 800,000 in 1988.3 The fraction of new arrivals to state prisons convicted of drug charges rose from 8 percent to 30 percent in the same period.4

The change in tone, though, reflects the fact that Reagan’s early drug policy was often a response to the particular problems he faced, rather than an expression of a coherent ideology. For most of his first term, Reagan faced a series of supply-side drug problems. The rise of the brutal Medellin cartel in Colombia, and the ensuing wave of cocaine smuggling—first into Florida and then across the nation—prompted Reagan to go on the offensive, establishing task forces and seeking international cooperation.5 Domestically, when Reagan spoke about drugs—in his 1983 and 1984 State of the Union addresses, for example—he focused on their connection to crime, rather than drugs themselves. The most significant piece of federal drug-related legislation in Reagan’s first term was the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984—a 400-page overhaul of the federal criminal justice system which, among other things, restored federal mandatory minimums for drugs and expanded the use of asset forfeiture in combatting drug crime.6

By his second term, though, drugs had become an issue of concern for Reagan—not just because of their connection to crime, or because of international conflict, but on their own merit. What changed was that Reagan, like Nixon before him, faced an acute crisis precipitated by a specific drug: crack.

Cocaine, remember, saw its stock rise in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Peter Bourne was not the only physician lauding its qualities. In 1976, Harvard’s Lester Grinspoon and James Bakalar could comfortably write that “the most significant sociological fact about cocaine today is that it is rapidly attaining unofficial respectability in the same way as marihuana in the 1960s. It is accepted as a relatively innocuous stimulant, casually used by those who can afford it to brighten the day or evening.”7 This sense was reinforced by media coverage, which glamorized the “cocaine scene” and claimed that “cocaine is not addictive and causes no withdrawal symptoms,” citing doctors who happily backed up the claim.8

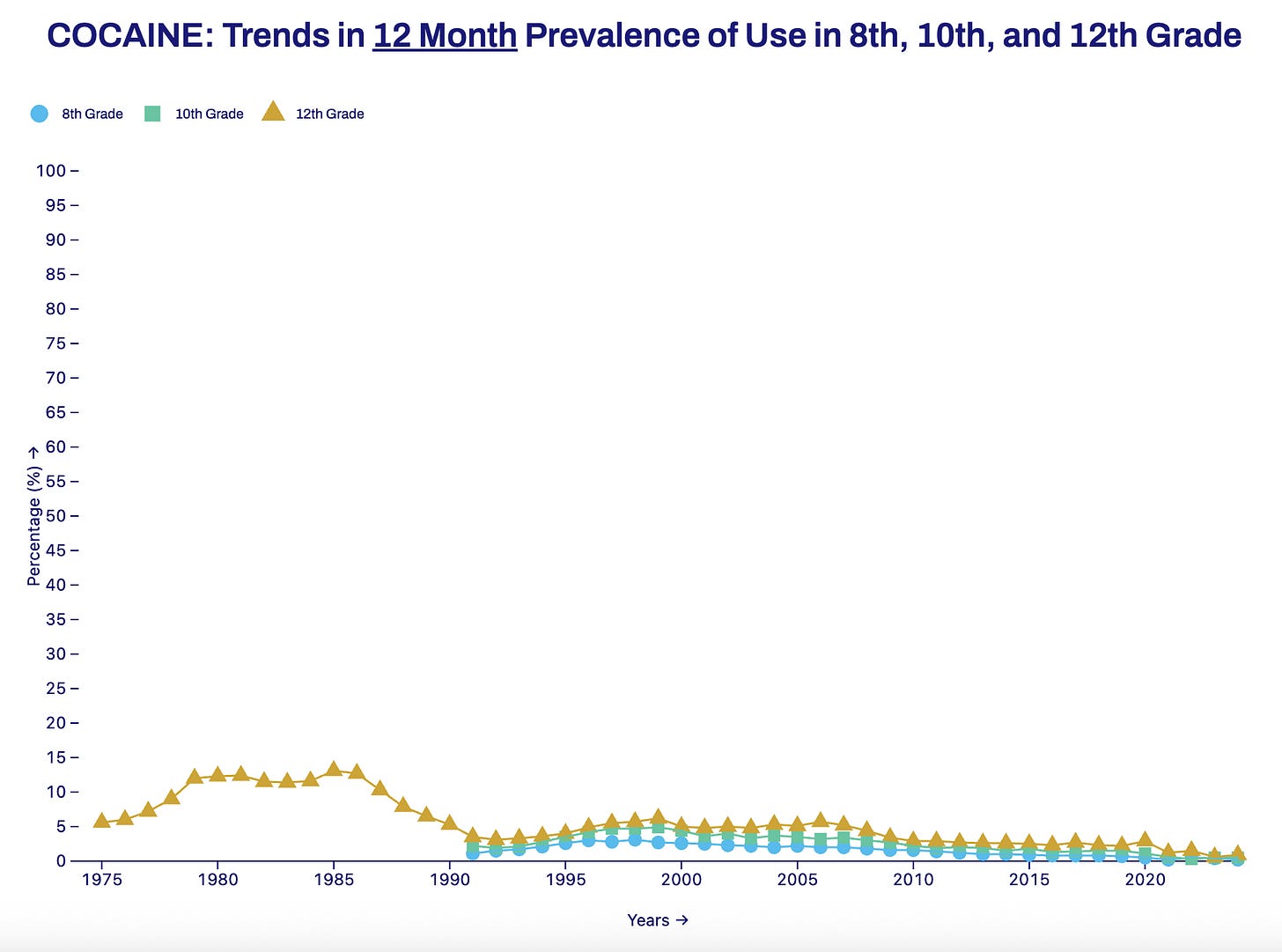

Use followed these cues. In 1976, about 6 percent of high-school seniors reported having used cocaine in the previous year. That rate doubled to 12 percent with the class of 1979, and peaked at 13 percent in 1985.9 In 1979, about 4.4 million Americans over 12 reported using cocaine on a monthly basis; the figure rose to 5.3 million by 1985.10 All of this use bred addiction: a nationwide cocaine hotline, opened in 1986, immediately began receiving thousands of calls a day. The callers were often high-class—lawyers, doctors, and engineers, many of them (contrary to popular perception) white. Their privilege didn’t protect them from reported insomnia, fatigue, headaches, sinus infection, depression, and irritability. Almost half claimed to have stolen to feed their habits.11

Just as for these men, the high of the cocaine culture was followed by a crash. For many, the precipitating event was the 1986 death of Len Bias, a University of Maryland basketball superstar. Bias was slated for NBA fame, and his sudden death from a cocaine overdose shocked a nation convinced that coke was basically benign. As one then-young reporter later told drug historian Jill Jonnes, “cocaine was still the perfect drug, a recreational drug that was not necessarily highly addictive. … Could cocaine really kill a six-foot-eight, two-hundred-pound guy?”12

Bias’s death, though, was just part of a broader transformation of the cocaine market. When it first hit the American scene, cocaine was a high-status, expensive drug. Low levels of supply kept prices high, restricting its use to the weekend parties of the glamorous classes. But as demand rose, and as the cartel infrastructure in Latin America expanded, supply increased, and price began to drop. In 1979, about 50 tons of cocaine entered the United States. Ten years later, the volume had risen to over 200 tons. In roughly the same period, prices fell over 75 percent. Cheap product facilitated heavier users’ transition from snorting cocaine to smoking it, which produces a faster and more intense high. Cocaine powder was boiled with ammonia or baking soda, creating a rock of “freebase” cocaine, which, when smoked, produced a cracking sound—thus the name.13

Crack spread quickly. In 1984, among a group of misdemeanor drug offenders in Manhattan, 42 percent tested positive for cocaine. Two years later, the rate had doubled to 83 percent. By June of 1986, Newsweek would claim that crack was in seventeen major cities and twenty-five states.14

At the same time that casual users were retreating from cocaine, then, would-be addicts were swept up by a wave of cheap, high-potency product. “Longtime addicts,” Jonnes writes, “whose other drug abuse had allowed some semblance of normal daily life were quickly lost to crack.”15 More addicting than powder cocaine, crack soon trapped its users in the cycle of binge and crash typical of stimulant addiction. Ethnographic accounts of crack-house life document how users spent most of their time either looking for or consuming “scotty” (as in Captain Kirk’s request “beam me up, Scotty!”). In between, their lives are portraits of dysfunction: frequent, destructive sexual relations, ruined families, a constant struggle to keep or find work.16

But what really set crack apart was the social devastation it brought. Crack houses were not merely places where people could get high; they were also a blight on the neighborhoods in which they sprang up. Women who found themselves trapped in the crack scene often traded, or were forced to trade, sex for drugs, and prostitution around crack houses was common.17 Crack use during pregnancy often resulted in small, fragile, sickly newborns—so-called “crack babies,” whom many feared would grow up permanently disabled. (Those fears turned out to be overstated, although children exposed to cocaine in utero are at risk for a variety of worse outcomes.)18 All of these problems were particularly acute within poor, black communities. One analysis, which measured the spread of crack using a composite of different measures, found that the drug’s rise between 1984 and 1989 explained roughly a third of the increase in low birth-weight black babies, and “much or all of the increase in Black child mortality and fetal death.”19

At the same time, crack markets were distinguished by their uniquely high levels of violence. Historically, street-level drug dealing had been dominated by organized crime rackets.20 But crack was different: disorganized street gangs became the main distributors, and engaged in bloody wars over the turf on which they sold.21 One scholarly analysis found that homicide rates among young, black men doubled after crack first appeared in a given city, and that that effect persisted nearly two decades later. By the year 2000, the data suggest, eight percent of all murders were still attributable to the long shadow of the early crack markets.22

It should therefore not surprise readers—although it may anyway—to learn that black Americans began to vocally endorse a renewed War on Drugs. While the anti-drug movement of the 1970s had been, with some conspicuous exceptions, a majority white phenomenon, anti-drug activism in the era of crack was increasingly led by black Americans. By 1986, drug historian Emily Dufton writes, “minority activists were forming parent groups of their own in urban areas across America, and centering their fight on adolescent use of significantly harder drugs like crack, heroin, and PCP.”23 Indeed, the first of the “Just Say No" clubs was probably organized by Joan Brann, a black activist in Oakland, California, at the instigation of twelve-year-old Nomathemby Martini.24

Typical of this new, black movement was the Philadelphia anti-drug activist Herman Wrice. Raised in the predominantly black Mantua neighborhood, Wrice had a history of community organizing stretching back to the 1960s. Crack first came to his attention when students on the baseball team he coached started showing up high to games. Wrice and a group of other fathers marched on a nearby crack house with protest signs. Wrice—six foot four and armed with a sledgehammer—advanced on the house, only to find that its denizens had fled in terror; he and the other dads promptly boarded it up.25

What started as one protest became many. Organizing Mantua Against Drugs—which would eventually become the Philadelphia Anti-Drug Coalition—Wrice and other community members held all-night vigils on crack corners, protesting to demand their streets back. With the support of the Clinton Department of Justice, Wrice soon took his street vigil method national; by 1996, he claimed to have trained over 350 communities.26

Wrice was far from the only black anti-drug activist. Groups like Washington, D.C.’s Fairlawn Coalition or Detroit’s REACH organized similar anti-drug protests.27 Many of these groups were peopled and led by black residents, angry at the drug dealing that had taken over their neighborhood. Contrary to contemporary assumptions, many were happy to work with the police in the name of bringing peace and order to their communities. In Los Angeles, groups like the Urban League decided that police misconduct was a “lesser evil” compared to drug gangs, and endorsed more policing to get crack under control.28

This popular action was matched by an aggressive federal response to the crack crisis. In a September 1986 address to the nation, President and First Lady Reagan sounded the alarm about drug abuse, and particularly about “a new epidemic: smokable cocaine, otherwise known as crack … an explosively destructive and often lethal substance which is crushing its users.” Reagan announced that he would soon debut a plan for a “drug-free America.”29

A month later, Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the signal legislation of the War on Drugs. The so-called “Len Bias Law” harshened federal drug-trafficking sentences and substantially increased funding for drug law enforcement.30 It also established mandatory minimum sentences for cocaine offenses, with a much smaller weight of crack versus powder cocaine—a 100-to-1 ratio—required to trigger the sentence.31 A major follow-up law, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, further enhanced the drug-control system, created the federal “drug czar” office, and declared the goal of a “drug-free America” by 1995.32

The ADAA was in part an expression of collective discontent within black communities about the drug situation. One of the key leaders in passing the 1986 ADAA was Rep. Charles Rangel, the black Democrat who had then already represented Harlem for 15 years. Drugs were Rangel’s “signature issue,” because he believed that every problem his constituents faced was linked to the drugs destroying their community.33 Thanks partly to Rangel’s leadership, most members of the Congressional Black Caucus backed the ADAA.34

Reagan’s most aggressive action against drugs really began only in the waning years of his administration. But his torch would be picked up by George H.W. Bush, arguably the president most committed to the drug war. In a famous televised address delivered a few months after he took office, Bush held up a bag of crack to millions of watching Americans and declared that “the war on drugs will be hard-won, neighborhood by neighborhood, block by block, child by child.”35

Under Bush—and Bill Clinton—the Drug War really took on the enforcement-driven character we associate with it today. In Reagan’s final year in office, the federal government spent about $2 billion per year on criminal-justice-related drug expenditures (arrest, prosecution, incarceration, etc.), and another $1.2 billion on interdiction. By the time Bush left office, in 1993, those figures were $5.7 billion and $2.1 billion. In 1998, midway through Clinton’s second term, it was $8.2 billion and $2.4 billion—more than $10 billion per year for fighting the War on Drugs.36 Drug arrests rose, and by 1994 police departments were collectively reporting over a million per year.37 In 1985, there were fewer than 40,000 people in state correctional facilities for drug offenses; by 1995, there were 225,000.38

Today, the Drug War is unpopular. But in its heyday it wasn’t. In 1988, a sizable majority of Americans said government drug policy should emphasize stopping drug importation and arresting drug dealers.39 A poll fielded days after Bush’s crack speech found that 64 percent of Americans called drugs “the nation’s most important problem.” A similar share reported that they favored Bush’s strategy for fighting drugs, and believed it would reduce the drug abuse problem.40 In many ways, this optimism remained: by the year 2000, 47 percent of Americans said they believed the nation had made progress in coping with the problem of illegal drugs, while just 29 percent believe they had lost ground. These were, respectively, the highest and third-lowest shares on record.41

But were they right? Was the War on Drugs actually getting the drug problem under control?

“The President’s News Conference,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, March 6, 1981, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/presidents-news-conference-0.

Author analysis of data from “Breakdown of National Drug Control Budget by Function (1981-1998),” Transaction Records Access Clearinghouse, accessed January 31, 2024, https://trac.syr.edu/tracdea/findings/national/drugbudn.html.

Author analysis of https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/102263/version/V15/view.

Darrell K. Gilliard, “Prisoners in 1992,” Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin (Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 1993), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p92.pdf.

“1980-1985” (Drug Enforcement Administration), accessed January 31, 2024, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-04/1980-1985_p_49-58.pdf; Ronald Reagan, “Remarks Announcing Federal Initiatives Against Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime,” https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/remarks-announcing-federal-initiatives-against-drug-trafficking-and-organized-crime; Joel Brinkley and Special To the New York Times, “4-Year Fight in Florida ‘Just Can’t Stop Drugs,’” The New York Times, September 4, 1986, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/04/us/4-year-fight-in-florida-just-can-t-stop-drugs.html.

https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/comprehensive-crime-control-act-1984-0

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 307–8.

Jonnes, 308.

Monitoring the Future.

Author analysis of 1979 and 1985 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse data.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 331.

Jonnes, 334.

Terry Williams, Crackhouse: Notes from the End of the Line, Reprint edition (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 8–9.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 376–77.

Jonnes, 377.

Williams, Crackhouse.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 378.

John P. Ackerman, Tracy Riggins, and Maureen M. Black, “A Review of the Effects of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure Among School-Aged Children Abstract,” Pediatrics 125, no. 3 (March 2010): 554–65, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0637; Stacy Buckingham-Howes et al., “Systematic Review of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Adolescent Development,” Pediatrics 131, no. 6 (June 2013): e1917–36, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0945.

Roland Fryer et al., “Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact,” Economic Inquiry 51, no. 3 (2013): 1651–81.

Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams, 379.

Steven D. Levitt and Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh, “An Economic Analysis of a Drug-Selling Gang’s Finances*,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115, no. 3 (August 1, 2000): 755–89, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554908.

William N. Evans, Craig Garthwaite, and Timothy J. Moore, “Guns and Violence: The Enduring Impact of Crack Cocaine Markets on Young Black Males,” Working Paper, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2018), https://doi.org/10.3386/w24819.

Dufton, “Just Say Know,” 184.

Dufton, 207.

Charles Fain Lehman, “Herman Wrice’s War on Drugs,” City Journal, Autumn 2022, https://www.city-journal.org/article/herman-wrices-war-on-drugs/.

Lehman.

Saul Neiman Weingart, Francis X. Hartmann, and David Osborne, Case Studies of Community Anti-Drug Efforts (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, 1994).

Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, New Edition (London New York: Verso, 2006), 272.

“Address to the Nation on the Campaign Against Drug Abuse,” Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, September 14, 1986, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-nation-campaign-against-drug-abuse.

Harry Hogan et al., “Drug Control: Highlights of P.L. 99-570, Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1986” (Office of Justice Programs, October 31, 1986), https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/drug-control-highlights-pl-99-570-anti-drug-abuse-act-1986.

Deborah J. Vagins and Jesselyn McCurdy, “Cracks in the System: Twenty Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law” (American Civil Liberties Union, October 2006), https://www.aclu.org/wp-content/uploads/document/cracksinsystem_20061025.pdf.

“H.R.5210 - 100th Congress (1987-1988): Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988,” legislation, Congress.gov, November 18, 1988, 1988-08-11, https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/house-bill/5210.

Michael Javen Fortner, “The Drug War: Race and Reality,” Vital City, December 13, 2023, https://www.vitalcitynyc.org/articles/the-drug-war-race-and-reality.

Michael Javen Fortner, “Niskanen Senior Fellow Michael Javen Fortner Submits Testimony for Hearing on the EQUAL Act - Niskanen Center” (Hearing by the Senate Committee on the Judiciary Regarding the EQUAL Act and Federal Sentencing for Crack and Powder Cocaine, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, June 21, 2021), https://www.niskanencenter.org/michael-javen-fortner-submits-testimony-for-hearing-on-the-equal-act/.

Special to The New York Times, “Text of President’s Speech on National Drug Control Strategy,” The New York Times, September 6, 1989, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/06/us/text-of-president-s-speech-on-national-drug-control-strategy.html.

“Breakdown of National Drug Control Budget by Function (1981-1998).”

Author analysis of https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/102263/version/V15/view.

“Correctional Populations in the United States, 1995” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, June 1997), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpius951.pdf.

“Interdiction and Incarceration Still Top Remedies” (Pew Research Center, March 21, 2001), https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2001/03/21/interdiction-and-incarceration-still-top-remedies/.

Richard L. Berke, “Poll Finds Most in U.S. Back Bush Strategy on Drugs,” The New York Times, September 12, 1989, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/12/us/poll-finds-most-in-us-back-bush-strategy-on-drugs.html.

“Interdiction and Incarceration Still Top Remedies”

Now, if women realize the most important role/responsibility they play is to mother the next generation of healthy, intelligent and successful children, and men wanted women for more than just sex...and if elephants had wings (maybe) they could fly...

I see drugs as a female problem. Men want sex, girls like drugs, so men give girls drugs to get sex. Those girls get pregnant and bring addicted babies into the world, which creates a self-reinforcing do-loop. The "momification" of America, single parent (female) families, "fatherless" children, women's "liberation", DEI/"woke"/affirmative action all play into it. Kids used to go to college to study, now they go for sex and drugs. Women used to go to find a good husband...now the men are all "momified", too...