What Was The War on Drugs? Part V

Two Cheers for the War on Drugs

Previously: The Reagan Era

This essay series has made three arguments about the War on Drugs. One is that it is a misnomer to identify one grand “War on Drugs,” stretching from Nixon to today. This is because, two, the War on Drugs came out of federal policy responses to several concrete drug problems—heroin, adolescent use, crack—rather than out of a consistent ideological response to drugs. Most importantly, three, the War on Drugs was a response to popular, grassroots outrage at those drug problems—an expression of the popular will which democracies are designed to channel.

What has received less focus up to this point is the actual effectiveness of the War on Drugs. Broadly speaking, the Reagan-Bush-Clinton drug war consisted of a dramatic increase in drug-related enforcement, supplemented by a substantial increase in prevention messaging, and by a government-led cultural backlash against drugs. Did these interventions actually work?

Some of the most aggressive criticisms of the Drug War’s implementation are unmerited. Most significantly, critics routinely charge the War on Drugs with being the major cause of America’s uniquely high incarceration rate. The U.S. prison population rose from less than 200,000 in 1970 to over 1.5 million at its peak in the late 2000s.1 Locking up “low-level, non-violent” drug offenders, it is often claimed, was the major driver of this nearly seven-fold increase. For example, in her oft-cited book The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander declares that “in less than thirty years, the U.S. penal population exploded … with drug convictions accounting for a majority of the increase.”2

This is, simply, false. Drug offenders never accounted for a particularly large fraction of the U.S. prison population, peaking at about 22 percent of state prisoners in 1990.3 (Today the rate is 13 percent.)4 The drug offender share did spike in the early 1980s. But as John Pfaff—a Fordham law professor and ardent critic of mass incarceration—has shown, other categories of offenders grew too, such that drug-related incarceration explains only about 20 percent of the growth in the prison population between 1980 and the population’s peak in 2009. Most of that contribution, furthermore, comes in the 1980s. From 1990 onwards, drug offenses account for only 14% of prison growth, compared to 60% attributable to violent offenders.5

The oft-used construction “low-level, non-violent drug offenders,” furthermore, implies a relatively benign population sent away by the War on Drugs. The implication is that our nation’s jails are filled with people whose worst crime is a couple of puffs on a joint. Again, the reality is quite different. One analysis of prison populations circa 1997—near the peak of the Drug War—found that just 2% of federal and 6% of state offenders were “unambiguously low-level,” meaning that they had no prior convictions or arrests, were not involved in a “sophisticated drug group,” and did not use a gun in their crime. The remainder either had some criminal history or concurrent offense, were involved in a drug dealing enterprise (often at a “middle management” level), or used a gun in their offense.6 Most of the drug offenders locked up in 1997, in other words, weren’t innocents swept up by the War on Drugs—they were people with serious involvement in drug dealing or criminal life. Indeed, that shouldn’t surprise readers. The crack epidemic caused unusually high levels of violence, and so enforcement against it tended to sweep up very violent offenders.

But, given that the War on Drugs’ involvement in mass incarceration is overblown, what did it actually accomplish?

It seems to have dramatically reduced the social harms of the crack epidemic. Crack houses declined in prevalence, as did associated prostitution. Most importantly, the push to lock up members of violent drug gangs was likely a significant contributor to the great decline in crime in the 1990s and 2000s. The economist Steven Levitt once estimated that the decline of crack in general probably explained about 15 percent of that drop.7

On the question of drugs themselves, it seems like Americans, especially teenage Americans, really did change their minds about how dangerous drug use was. Gone were the days of cocaine paraphernalia on magazine covers. For example, high-school seniors (the group for which we have the most data) in 1979 were relatively sanguine about cocaine: only 32 percent said there was “great risk” in trying it. By 1994, that figure peaked at 57 percent. Support for drug-law reform also sputtered out. In 1977, 28 percent of Americans said marijuana should be legal, a 16-point gain over the preceding eight years. In 1985, though, support was back down to 23 percent, and it rose only barely to 25 percent in 1995.8 The dream of marijuana legalization was dead for a generation.

Initially, the War on Drugs also had a remarkable effect on the total number of people using drugs. The share of high-school seniors using any illicit drug peaked in 1979, at 54 percent. It then fell more or less continuously for the next decade, bottoming out in 1992 at 27 percent. The class of 1992, in other words, was half as likely as the class of 1979 to use illicit drugs.9 Similarly heartening trends obtained in the adult population. In 1979, there were an estimated 25 million illicit drug users, including about 4.7 million cocaine users; 4.1 million had ever used heroin. By 1992, those numbers had fallen to 12 million, 1.4 million, and 1.7 million respectively.10

But then, somewhat alarmingly, progress slowed, and in fact slightly reversed. By the year 1997, there were an estimated 14 million illicit drug users, including 1.8 million cocaine users, and 2 million lifetime heroin users.11 Even more alarmingly, the trends among high schoolers reversed sharply, as 42 percent of the class of 1997 reported using illicit drugs. Some of that inversion is explained by marijuana smoking, but 21 percent of 1997 seniors used illicit drugs other than marijuana—up from 15 percent five years before.12

Stalled progress was particularly obvious among “hardcore” users. In a 2000 report, the Office of National Drug Control Policy estimated that there had been about 3.9 million hardcore cocaine users and 900,000 hardcore heroin users in 1988. Those figures fell to 3.3 million and 700,000 by 1992. But then progress stopped or reversed, and by 2000 there were still 3.3 million hardcore cocaine users, and again 900,000 hardcore heroin users.13 And because heavy users consume most of the volume of drugs consumed, the estimated volume of drugs actually used was essentially unchanged between 1985 and 1995.14

As early as 1993, the drug czar’s office was sounding the alarm on slowing progress. In a section of its National Drug Control Strategy, it noted that “two distinct fronts are emerging in the war on drugs”—casual drug users and “hard-core addicted users,” who were more resistant to efforts to reduce their use. “Until we can succeed in making … drugs less readily available on our streets,” the report read, “at higher prices and at lower purity, it will be difficult to make continued headway against hard-core drug use.”15

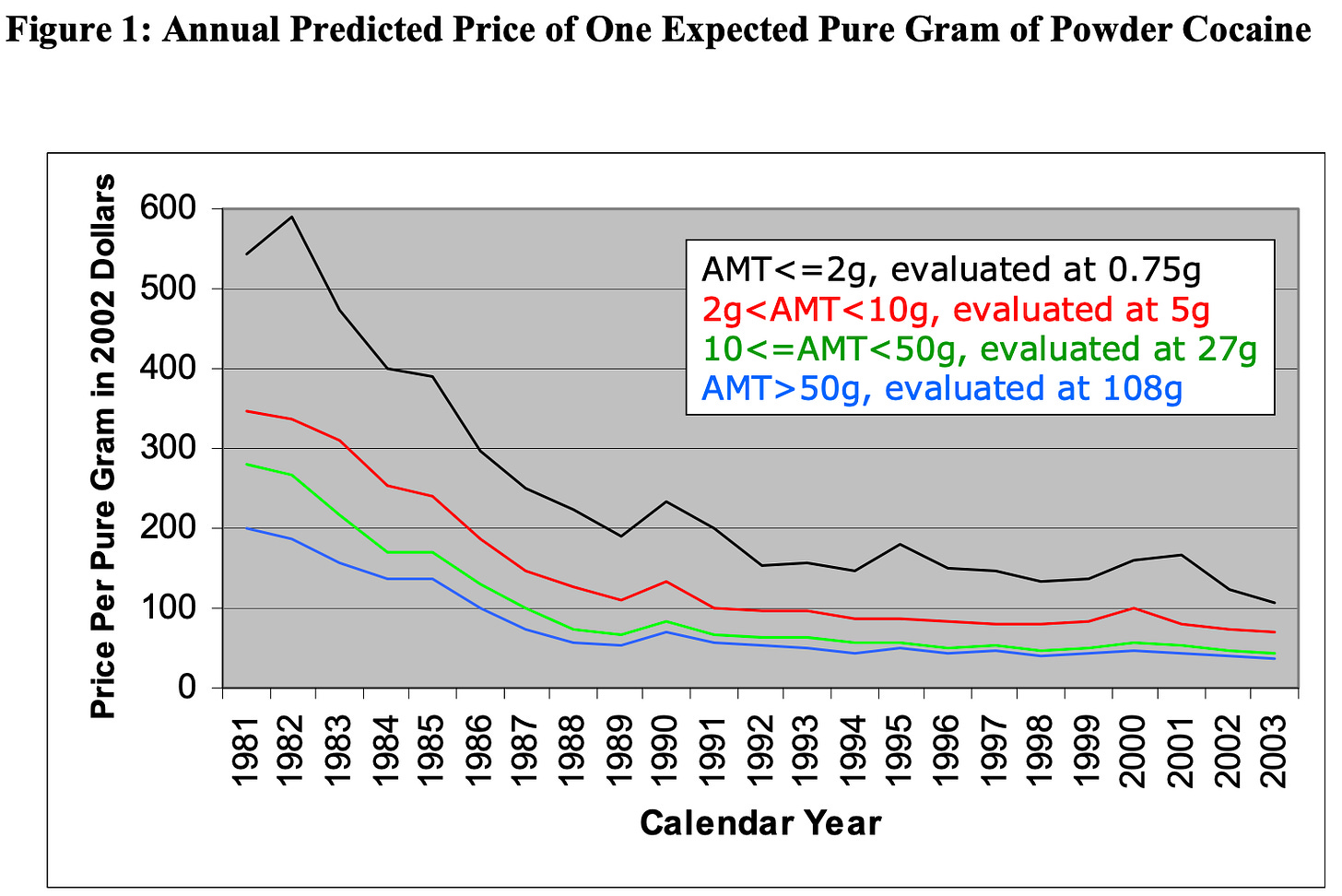

Prices did not rise, and purity did not decline—indeed, the opposite happened. Between 1982 and 1992, the purity-adjusted price of cocaine fell by 75%, then leveled out. The purity-adjusted price of heroin fell by about two-thirds between 1990 and 2003, while purity actually rose.16 After two decades of the War on Drugs, in other words, drugs were much cheaper and more potent than they were when the War on Drugs began.

One way to interpret this evidence is that the War on Drugs was remarkably successful at increasing the social opprobrium around drugs. Public education campaigns like the “Just Say No” movement plausibly played a role in convincing the general public that drugs were bad and harmful. As a consequence, more and more casual users chose sobriety.

But by the available evidence, the War on Drugs was far less successful at reducing use among the “hard core” of users, mostly meaning people addicted to their drug of choice. And because heavy users account for the majority of use—because one person who uses three times a day uses more than 20 people who use once a week—reducing casual use could only have a relatively small impact on the total level of drug use, and, by some measures, drug harm.

Reducing use was a major priority of the drug war program. As early as 1989, the drug czar’s office identified the “essence” of the problem as “use itself.” “The simple problem with drugs,” the 1989 National Drug Control Strategy claimed, “is painfully obvious: too many Americans still use them. And so the highest priority of our drug policy must be a stubborn determination further to reduce the overall level of drug use nationwide - experimental first use, ‘casual’ use, regular use, and addiction alike.”17

But of course, not all drug use is equally harmful. All drugs carry a risk of addiction—by definition—but people can and do use drugs casually without lasting harm. That’s obviously true of alcohol, but it’s also true of “hard” drugs like heroin.18 That doesn’t mean readers should rush out and score some junk. It’s very hard to know in advance if using drugs will lead to harm—that’s what makes them risky. At the same time, though, it means that not all drug users do equal amounts of harm to themselves and to others. And an exclusive focus on reducing overall use levels can obscure this fact.

On the one hand, there were probably real benefits to reducing the number of people—especially the number of teenagers—doing drugs casually. On the other, the drug war’s fixation on drug use stigmatized those who continued to use as moral failures to be “held accountable” for their choices.19 The “brain disease” model of addiction, popularized in a 1997 paper by then-director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Alan Leshner, was in part designed to argue that drug use was a health issue, not a moral failing. As Leshner put it, “the gulf in implications between the ‘bad person’ view and the ‘chronic illness sufferer’ view is tremendous. As just one example, there are many people who believe that addicted individuals do not even deserve treatment. This stigma, and the underlying moralistic tone, is a significant overlay on all decisions that relate to drug use and drug users.”20

Attaching strong moral opprobrium to drug use, and aggressively enforcing against it, might have been justified if it changed hardcore users’ behavior. Tough love can be worth it if it saves lives. But the evidence from users, levels of use, and price all suggest it wasn’t. Why not? Why didn’t a million arrests a year appreciably change the use behavior of people in addiction? The answer, somewhat interestingly, comes down to economics.

How drug enforcement affects drug use is a deceptively simple question. Intuitively, if a drug dealer or a load of drugs is taken off the street, the quantity available goes down. If the quantity of drugs available goes down, Econ. 101 tells us, the price will go up.21 Less product available at higher prices should mean that, all else being equal, people will consume fewer drugs.

But not all drug enforcement affects prices equally. In a famous 1986 paper, drug policy scholars Mark A. R. Kleiman and Peter Reuter observed that the price of drugs rose substantially between points on the supply chain. The ten kilograms of opium needed to make one kilogram of heroin, for example, cost about $1,000 at the farm gate. When it enters the United States, that same kilogram costs about $200,000 per kilogram—most of the added price comes in the intermediary steps. As a result, even very large fluctuations in the farm-gate price—dropping to $100, or tripling to $3,000—would have only marginal effects on the final price of heroin on the street. Thus, Reuter and Kleiman argue, enforcement efforts targeting source countries or interdiction probably do very little to affect consumption.22

But by this logic, street-level enforcement should still have some effect on the consumption of drugs. How much, though, is a different question. Economists have a concept, “elasticity,” which refers in part to how much people will change their consumption of a good in response to a change in the price of that good. If the price of, for example, kale, goes up one percent, people will buy less kale. If the amount of kale consumed falls by more than one percent in response, the demand for kale is said to be “elastic.” If it falls by less than one, then demand is said to be “inelastic.” The less elastic demand for a good is, the bigger the change in the price has to be to reduce the quantity consumed. In drug-market terms, the less elastic demand for drugs is, the more enforcement is necessary to get a desired reduction in drug consumption.

A lot of research has tried to capture the elasticity of demand for drugs. A 2020 summary found that overall, demand was only minorly inelastic—for each 10 percent increase in the price of drugs, demand falls by about 9 percent. But that statistic obscures underlying differences. Specifically, studies of heavy users find that a 10 percent increase in the price of drugs will only reduce their use by around 3 or 4 percent.23 Some estimates go lower—one study that used data on arrestees, with urine tests as independent measures of their drug use, found that among heavy users a 10 percent increase in price reduces consumption of cocaine by 1.5 percent, and heroin by 1 percent.24

In other words, the way that people respond to drug enforcement depends on their habits. Casual users, less attached to their drug of choice, are prone to cutting back or not using altogether—just as they appear to have done during the 1990s. But heavy users—people who are addicted to drugs—face a significant cost from cutting back or quitting, whether it be the loss of euphoria or the suffering and risks involved in withdrawal.

That doesn’t mean enforcement can’t affect addicted users’ behavior—people suffering from drug addiction are not totally irrational, and they can and do respond to changing incentives.25 But it does mean that it takes much more enforcement to get an addict to change his or her level of behavior, relative to a non-addict.

Stated even more simply: it doesn’t take a lot of arrests and incarceration to get casual users to quit. But it does take a lot of enforcement to get the “hard core” to change their behavior. And while there in fact were very high levels of drug enforcement in the 1980s and 1990s, these levels do not seem to have been high enough to make an appreciable dent in the population whose drug problems were most acute and most harmful.

Faced with these facts, one response is to say War on Drugs simply didn’t go far enough. If the level of enforcement in the 1990s wasn’t high enough to really reduce hardcore drug use, we simply need to do more. And, empirically, it is the case that super-tough crackdowns on drugs can curtail drug problems, as the Chinese Communist Party and the Taliban have both shown.26 But such crackdowns have costs too—in criminal-justice expenditures, and in lives and liberty lost. More to the point, it is unlikely that a liberal, democratic society like America’s would tolerate such a crackdown, particularly given the political unpopularity of the comparatively mild enforcement regime of the 1980s and 1990s. If the War on Drugs is so unpopular, imagine how unpopular a war modeled on the Taliban would be.

Another response would be to argue that drug enforcement isn’t worth the costs. In a very weak sense, this is true: enforcement could at least plausibly be reduced at the margins, as indeed it has been since its peaks in the 1990s. But the stronger conclusion—that cops should have no role in handling the drug problem—is something else entirely. As I argue elsewhere, there are clever enforcement strategies that overcome the problems identified in the last section. Policing drugs smarter, not harder, can have real impact on drug-related harms.

Although the War on Drugs stalled—predictably—in its efforts to create a “drug-free America,” it does not deserve its reputation as a destructive, racist failure. It deserves to be better remembered, in part because of what it was: a popular backlash against serious, community-wrecking problems with drugs that arose in the ‘70s and ‘80s. That same backlash probably substantially reduced the number of people using drugs. It helped turn the tide on the drug culture, and helped tamp down the worst excesses produced by that culture, from crappy magazines to crack houses. That it failed at its most important task is still a far weaker criticism than those so often leveled against it.

Demonizing the drug war has long been a key weapon in the arsenal of liberalizers. When we recognize it for what it was—a noble and reasonable, if fundamentally flawed, experiment—then that weapon should lose some of its power. The future of American drug culture isn’t, and shouldn’t be, a new War on Drugs. But it shouldn’t be a rejection of its ethos either, not properly understood.

Ashley Nellis, “Mass Incarceration Trends,” The Sentencing Project, January 25, 2023, https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/mass-incarceration-trends/.

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2012), 6. Alexander bases this claim on Marc Mauer, Race to Incarcerate (New York: The New Press, 2006), 33. What Mauer actually writes is “more than half (55 percent) of the new inmates added to the system in this decade were incarcerated for a nonviolent drug or property offense [emph. added]. The impact of drug policies on the federal prison system is even more dramatic, with drug offenses alone accounting for two thirds (65 percent) of the rise in the inmate population between 1985 and 2000.” On the opposite page, Mauer reports that drug offenders account for 28 percent of the increase in incarceration between 1985 and 2000 (p. 32, table 2-2). Alexander’s looseness with numbers is not atypical of the pro-decarceration movement.

John F. Pfaff, “The War on Drugs and Prison Growth: Limited Importance, and Limited Legislative Options,” Harvard Journal on Legislation 52 (2015): 173–220.

E Ann Carson, “Prisoners in 2021 – Statistical Tables” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, December 2022), https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/p21st.pdf The drug-offender share for federal offenders is consistently much higher — usually around half. But the federal prison population itself is usually only about 10% of the total prison population of the United States, so this larger share does not do much to shift the overall composition.

Pfaff, “The War on Drugs and Prison Growth: Limited Importance, and Limited Legislative Options.”

Eric L. Sevigny and Jonathan P. Caulkins, “Kingpins or Mules: An Analysis of Drug Offenders Incarcerated in Federal and State Prisons,” Criminology & Public Policy 3, no. 3 (2004): 401–34, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2004.tb00050.x.

Steven D Levitt, “Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors That Explain the Decline and Six That Do Not,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18, no. 1 (February 1, 2004): 163–90, https://doi.org/10.1257/089533004773563485.

Lydia Saad, “Grassroots Support for Legalizing Marijuana Hits Record 70%.”

https://monitoringthefuture.org/results/data-access/tables-and-figures/. Trends are similar using similar time periods or discounting marijuana use.

Table 2, “National Drug Control Strategy” (Office of National Drug Control Policy, February 2002), 58, https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ondcp/192260.pdf.

Table 2, “National Drug Control Strategy,” 58.

Monitoring the Future.

William Rhodes et al., “What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs 1988-1998” (Office of National Drug Control Policy, December 2000), https://www.ojp.gov/ondcppubs/publications/pdf/spending_drugs_1988_1998.pdf.

Ilyana Kuziemko and Steven D Levitt, “An Empirical Analysis of Imprisoning Drug Offenders,” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9–10 (August 2004): 2043–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(03)00020-3.

“National Drug Control Strategy: Progress in the War on Drugs 1989-1992” (Office of National Drug Control Policy, January 1993), https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ondcp/140556.pdf.

“Price and Purity of Illicit Drugs: 1981 Through the Second Quarter of 2003” (Office of National Drug Control Policy, November 2004), https://www.ojp.gov/ondcppubs/publications/pdf/price_purity.pdf; Arthur Fries et al., “The Price and Purity of Illicit Drugs: 1981 – 2007” (Institute for Defense Analyses, October 2008).

“National Drug Control Strategy,” September 1989.

G. Harding, “Patterns of Heroin Use: what do we know?,” British Journal of Addiction 83 (1988): 1247–1254, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb03035.x.

“National Drug Control Strategy.”

Alan I. Leshner, “Addiction Is a Brain Disease, and It Matters,” Science 278, no. 5335 (October 3, 1997): 45–47, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.278.5335.45.

To be more precise, drug enforcement shifts the supply curve up and to the left, reducing the market-clearing quantity and increasing the market-clearing price. For further discussion see Jonathan P. Caulkins and Peter Reuter, “How Drug Enforcement Affects Drug Prices,” Crime and Justice 39, no. 1 (2010): 213–271, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/652386.

Peter Reuter and Mark A.R. Kleiman, “Risks and Prices: An Economic Analysis of Drug Enforcement,” Crime and Justice 7 (January 1986): 289–340, https://doi.org/10.1086/449116.

Jason Payne et al., “The Price Elasticity of Demand for Illicit Drugs: A Systematic Review,” Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (Australian Institute of Criminology, October 6, 2020), https://doi.org/10.52922/ti04800.

Dhaval Dave, “Illicit Drug Use among Arrestees, Prices and Policy,” Journal of Urban Economics 63, no. 2 (March 1, 2008): 694–714, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2007.04.011.

Jonathan P. Caulkins and Nancy Nicosia, “Addiction and Its Sciences: What Economics Can Contribute to the Addiction Sciences,” Addiction (Abingdon, England) 105, no. 7 (July 2010): 1156–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02915.x.

Jonathan P. Caulkins and Keith Humphreys, “New Drugs, Old Misery: The Challenge of Fentanyl, Meth, and Other Synthetic Drugs” (Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, November 9, 2023), https://manhattan.institute/article/the-challenge-of-fentanyl-meth-and-other-synthetic-drugs/.

“Stated even more simply: it doesn’t take a lot of arrests and incarceration to get casual users to quit. But it does take a lot of enforcement to get the “hard core” to change their behavior. And while there in fact were very high levels of drug enforcement in the 1980s and 1990s, these levels do not seem to have been high enough to make an appreciable dent in the population whose drug problems were most acute and most harmful.”

So the question is then why not just target these individuals with intensive, mandatory rehab terms? I imagine they are not hard to identify.

Seems like the sweet spot is what we had in the 80s and 90s — moderate enforcement (not Taliban-level) and a govt-led culture of messaging on its harms (“Just Say No”).

While the formation of hardcore users may be harder to prevent, we are much better off with a lot less “casual” users, because even mild to moderate use of drugs is destructive to many lives and society generally.