Anatomy of a Ferguson Cycle

Why homicide rose, why it fell, and why it will rise again

Back in 2015, my Manhattan Institute colleague Heather MacDonald popularized the term “Ferguson effect” to refer to a dramatic increase in homicide which (the term and she implied) was caused by the wave of protests, in turn instigated by the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., the year before. The homicide rate rose 11 percent in 2015, and another 10 percent in 2016, before cresting and receding. This, MacDonald and others argued at the time, was the result of a reduction in police proactivity, itself caused by political attacks on and criticism of the police in the wake of Brown’s death (among other high-profile incidents).

For a long time, critics of the Ferguson effect insisted that it was unscientific, “debunked,” or otherwise had run afoul of some isolated demand for rigor. This is, in my view, not a serious position for someone to take—not really at the time, and certainly not now. As my colleague Robert VerBruggen noted back in 2016, much of the evidence trotted out to disconfirm the Ferguson effect actually supported it. Since then, several higher quality studies have, using plausibly causal designs, established a strong relationship between high-profile police shooting incidents and protests thereof, depolicing, and increases in crime. It is, I think, reasonable to argue about the magnitude of the Ferguson effect, or whether it is at play in any given situation. But the idea that there is no relationship between high-profile protests of the police and subsequent increases in violence does not, in my view, withstand scrutiny.

What was interesting about the 2014-2016 homicide spike was that it appeared to recede much more quickly than the great crime wave of the 1960s-1990s. If opponents of the Ferguson effect theory were wrong to deny its existence, proponents were often wrong in saying the 2015/16 increases heralded a new explosion of crime. Homicide went up, then it went down—a blip, relative to the long-term trend since the peaks of the 1980s.

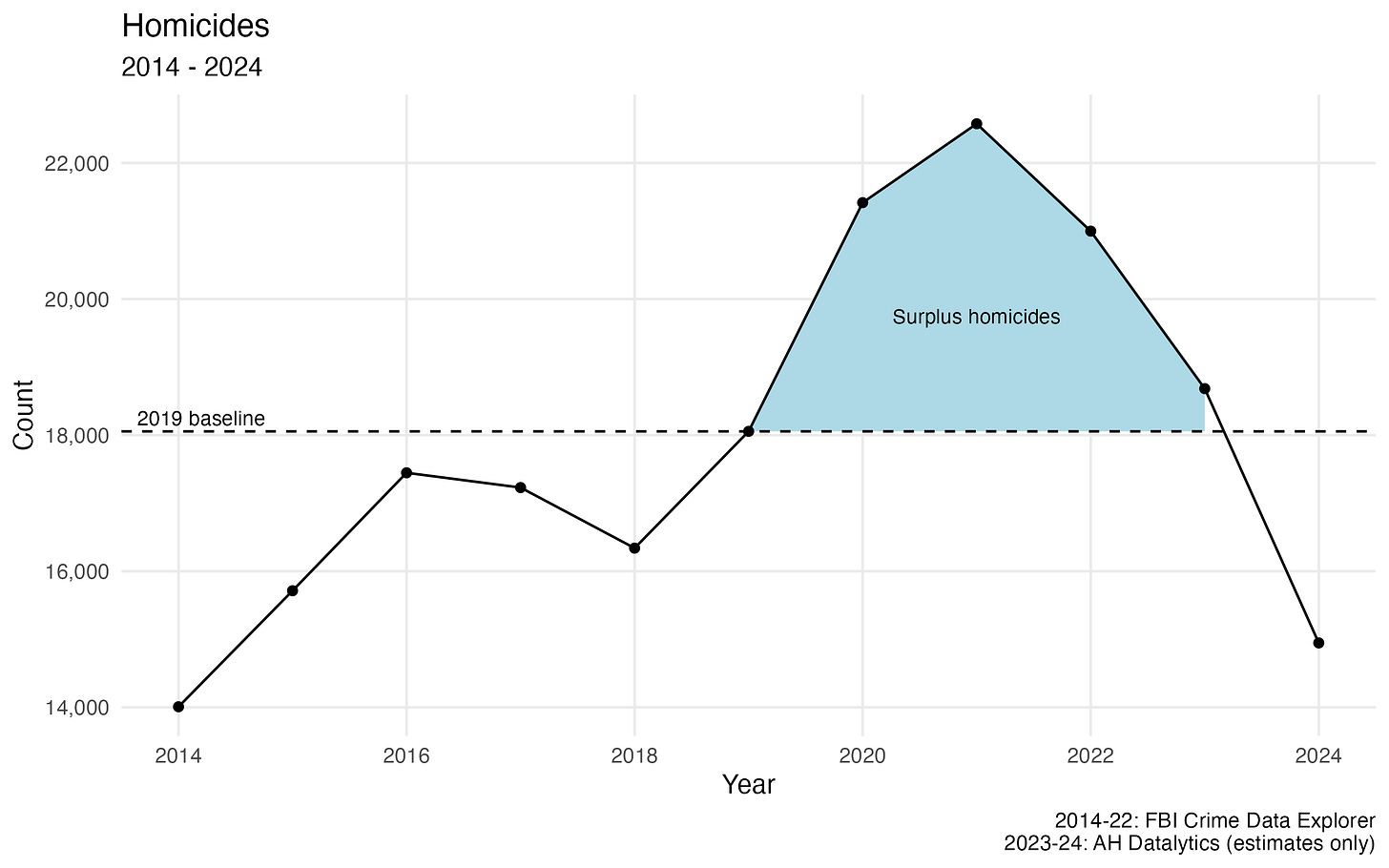

I’ve been thinking a lot about that first wave in trying to understand what’s happened over the past five years. As Jeff Asher at Jeff-alytics has been reporting, homicide rates rose in 2020, probably peaked in 2021, have fallen steadily since then, and are on pace to return to 2019 levels or below in 2024. Jeff’s 2023/24 figures are based on a sample of 180 cities with data; while that’s not the official homicide rate (i.e. the figure the FBI reports), past years have proved to be pretty good measures of the final number. (See the data and comparisons here.)

The decline in homicide rates got picked up by the Wall Street Journal (paywalled) over the weekend, and attracted a fair amount of discussion on Twitter. A lot of the commentary was, bluntly, bad: discussion of the inconsistency of the media’s treatment of these trends,1 or claims that the trends were fake, or insistence that this proved there was no homicide problem all along.

But what should we make of this trend? And how does someone like me—a professional tough-on-crime guy—respond to the decline? After all, I’ve been saying for years that America has a substantial crime problem. Doesn’t this prove me wrong? Obviously, I don’t think it does. In fact, I have been predicting since 2021 or so that we’d see a mean reversion in homicides, much as we did after 2014-2016. The 2020-2023 experience, in my view, confirms that there is a new phenomenon driving trends in the post-crime-decline world: the Ferguson effect.

One way to think about the Ferguson effect is as an exogeneous shock that temporarily disrupts the equilibrium state of the criminal justice system. At time t = -1, the system is chugging along at some steady state of crime and punishment. At time t = 0, a high-profile police shooting incident leads to massive protests, in turn triggering wariness among the police, officer resignations or transfers, and hostility to proactive enforcement among civilian policymakers. Criminals—particularly the most prolific offenders—respond to the reduction in deterrence by settling old beefs or starting new ones. Eventually, the anger fades, countervailing policy pressures push proactivity back up, and/or ping-pong murder cycles burn out as the active players end up dead or incarcerated. At time t = 2 or 3 years, the system returns to its equilbrium state.

Importantly, I am claiming that the Ferguson effect does not necessarily alter the determinants of that equilibrium state, which is the product of both policy and structural variables. One of the reasons the Great Crime Wave happened, for example, is that the Baby Boom generation aged into and then out of their peak offending years—age structure alone explains about half of the boom and bust. In the short run, ambient technological surveillance causes Ferguson cycles (because everyone is recording everything all the time, including police altercations). But in the long run, ambient technological surveillance probably reduces the equilibrium level of crime (because everyone is recording everything all the time, including crimes). On the policy side, we forget how much pessimism there was about the capacity of policy to have any impact whatsoever on crime throughout most of the 1970s and 1980s. Policing was underutilized, and incarceration deployed unintelligently. (I write about some of this here.) The Great Crime Decline is partially attributable to policymakers discovering very elementary facts about fighting crime, facts like “if you put cops in a place, people won’t commit crimes in that place.”2

The long-term rise and fall of violent crime in the 20th century, I would assert, was a structural phenomenon—it reflected fundamental shifts in these underlying variables.3 The spikes in homicide that we are experiencing today are different. Ferguson cycles—high-profile police incidents, protests, temporary reduction in proactivity, then mean reversion—are deviations from the basic trend, caused by exogenous shocks to the system.

That kind of short-run deviation is pretty clearly what happened 2020-2023. I wrote about this as “the Minneapolis effect” back in 2021: Police activity measurably and substantially declined in the immediate aftermath of the George Floyd protests, resulting in large upticks in violence. In some places, at least, activity has rebounded. In New York, for example, police stops fell to less than 800 per month in 2020/21; as of 2023, they’re back at about 1,400 per month, above the 2019 baseline of about 1,100. in Washington, D.C., an increase in police activity has similarly coincided with a decrease in that city’s homicide rate. Other cities have stepped up hiring or unwound 2020-era reforms. As the 2020 protests have receded, in other words, they’ve returned to their pre-shock state.

Moreover, the Ferguson effect is not (bizarre claims to the contrary notwithstanding) a particularly unreasonable causal story to tell. Policing causally reduces crime. When the public and civilian leadership say that at the margin they will be more punitive towards police, police respond by reducing their activity levels. When those activity levels go down, crime goes up.

In short: the mean reversion we’re currently seeing is more or less what we should expect if the Ferguson effect accurately describes reality, and if we just went through a Ferguson “cycle” as I’ve described it.

But does that mean that we don’t need to worry about homicide anymore? We’re not going back to the “big days” of the 1980s, and homicide rates are well below historic norms, so it’s not really an issue, right? Not exactly.

The fact that Ferguson cycles are deviations from trend doesn’t mean that they aren’t a major problem. The above chart shows the number of homicides from 2014 to 2024. If we take (for sake of discussion) 2019 as the baseline homicide level, then the increase in homicides potentially attributable to the 2020 Ferguson cycle represents some 20,000 surplus homicides. That’s a lot of dead people who aren’t dead at baseline! You can do a similar estimation using 2014’s figures, and the totals look even worse.4

Moreover, in the abstract it is possible to imagine a short-run deviation altering the underlying determinants of crime. If protests instigate policy changes that make enforcement systematically less effective, that will have an effect. Similarly, if some communities become systematically less policed, that can have a durable effect. Cities with large black populations were most likely to experience a Ferguson effect the last time around; notably, the black homicide rate has never reverted to its 2014 baseline.

The point of this post, though, is that the character of the national homicide problem is different today. 40 years ago, the problems were about the fundamental determinants of crime. We had lots of factors encouraging crime, and we didn’t know what policy tools to use to counter them. Today, the natural factors look pretty good (crime-wise, at least—a greying population is bad in other ways), and we *know* what works to control crime (at least moreso than we used to). But we have this separate problem where every five years or so, social unrest induces a predictable change in the level of policing, which in turn causes a predictable increase in the homicide rate.

One response to all this is, in essence, to express indignation that the world is thus. This takes the form of, for example, casting the decline in police proactivity as a “wildcat strike,” labeling police as whiners unwilling to listen to a little criticism. This is a bad argument for a couple of reasons. One is that it is untrue; the idea that criticism of the police in 2020 was uniformly reasonable and merited is absurd. But another is that public policymaking is not governed by the rules of the playground. Grant, arguendo, that the police are behaving childishly when they respond to protests by reducing activity. What, exactly, should policy do about it? Scold police officers until they enjoy getting spat on by protesters? If police officers respond predictably to protests, and if the result of that response is a major increase in homicide death, then we cannot just wish away the dynamic. That’s not how public policy works.

Let me expand on this point with one of the papers I link to above, Campbell 2024. The paper uses geocoded data on Black Lives Matter protests between 2014 and 2019, finding that they reduce police homicides by 10 to 15%, equivalent to about 200 deaths. But protests also increase the total number of homicides by 11.5%, while reducing property crime arrests and clearances—both of which Campbell takes as evidence of a Ferguson effect. There are, for those of you not aware, many more homicides total (about 15-20,000 per year) than there are police homicides (about 1,000 per year). So reducing the latter by 10 to 15% while increasing the former by 11.5% yields more deaths overall.

Does this mean that we should never protest when police do bad things? Obviously the answer is no. Protest is a fundamental civil right, and police misconduct is a grievous violation of the public trust. But even if the cause is noble, the effect may still be harmful. To refuse to acknowledge that in the name of principle is a good way for people to end up dead.

The cause, moreover, is often not noble. Unjustified police homicide, and brutality more generally, is vanishingly rare. There are smart reformist steps civilian leaders can and should take to make their police departments better. They should not, however, make political decisions on the basis of horrifying but wholly unrepresentative videos of the worst moments in policing. We can now say with a fairly high level of certainty that doing so kills people.

Saying that the Ferguson effect is the primary determinant of current homicide conditions says something about more than just the dynamics of reform, though. It says that the basic challenge of keeping cities safe today is not about structure or policy—it’s about politics. Ferguson cycles, after all, are instigated by social upheaval and politicians’ collective willingness to feed it. It is incumbent on those of us who care about keeping homicides low to point out that doing so has predictable, deadly consequences.

There is no doubt in my mind that 2020-23 is not the last Ferguson cycle. There will be another video, more protest, and more outrage. The question is whether we will learn from recent history, and recognize that giving into the impulse to make policy on the basis of videos is a dangerous one. Thousands of lives hang in the balance.

This kind of commentary—talking about how the media covers crime, rather than talking about crime per se—is often an attempt to distract from or downplay the underlying issue, i.e. the number of dead people and the trend therein. Even when it’s not, media criticism is just not the most important part of the criminal justice conversation.

“What about lead?” No, it’s still mostly not lead.

I recommend Barry Latzer’s book on the topic, The Rise and Fall of Violent Crime in America.

“But wasn’t the increase just COVID?” I deviate from a lot of other people on the right in thinking that COVID, and specifically COVID restrictions, probably explain some of the increase in homicide in 2020. But, as I explain in the Minneapolis effect article, it’s hard to tell a COVID-exclusive story. That’s because the spike comes a) only in the United States, and b) after George Floyd’s death, not after the onset of lockdowns. Asserting that the protests had nothing to do with the increase involves the kind of “it’s all a coincidence” handwaving that should not be taken seriously—again, isolated demands for rigor. But sure, let’s grant that COVID explains, I don’t know, 50% of the increase over 2019 baseline. That’s still 10,000 Ferguson-effect-attributable deaths! Which is a lot of dead people!

A pretty sensible summary of our current situation and the research. In my view the article GREATLY underappreciates the double whammy created by covid 19 beginning in Martch 2020. In Chicago at least, this very very quickly led to a big decline in discretionary enforcement activity, routine patrolling, responses to (usually false) alarms, issuing minor traffic citations, and the like. The coppers did a better jog at sustaining gun seizures and other important matters, but the covid whammy was a hard blow. You will recall that the rest of us also were trying to stay 10 feet from everybody and we locked our doors when we were exposed or even just got the sniffles - that was real life in the Terrible Twenties.

Wesley G. Skogan

> Grant, arguendo, that the police are behaving childishly when they respond to protests by reducing activity. What, exactly, should policy do about it?

The same thing we should do with teachers who refused to teach in person even after getting vaccines during COVID: ban public sector unions so that we can fire public employees who refuse to do their jobs.

(And, in fairness to police officers who actually are having a harder time, couple that with an increase in base pay so they don't end up just getting screwed).