Immigration as an Engineer's Triangle

Liberal Democracy, high rates, non-selectivity: choose two

David Leonhardt has a new essay in the New York Times magazine profiling the Danish Social Democrats. The piece is long, but the point is, in essence, that Danish leftists have bucked the continent-wide right-populist backlash by—unlike every other left-wing party—listening to voters on immigration.

Since the Social Democrats took power in 2019, they have compiled a record that resembles the wish list of a liberal American think tank. … But there is one issue on which Frederiksen and her party take a very different approach from most of the global left: immigration. Nearly a decade ago, after a surge in migration caused by wars in Libya and Syria, she and her allies changed the Social Democrats’ position to be much more restrictive. They called for lower levels of immigration, more aggressive efforts to integrate immigrants and the rapid deportation of people who enter illegally. While in power, the party has enacted these policies. Denmark continues to admit immigrants, and its population grows more diverse every year. But the changes are happening more slowly than elsewhere.

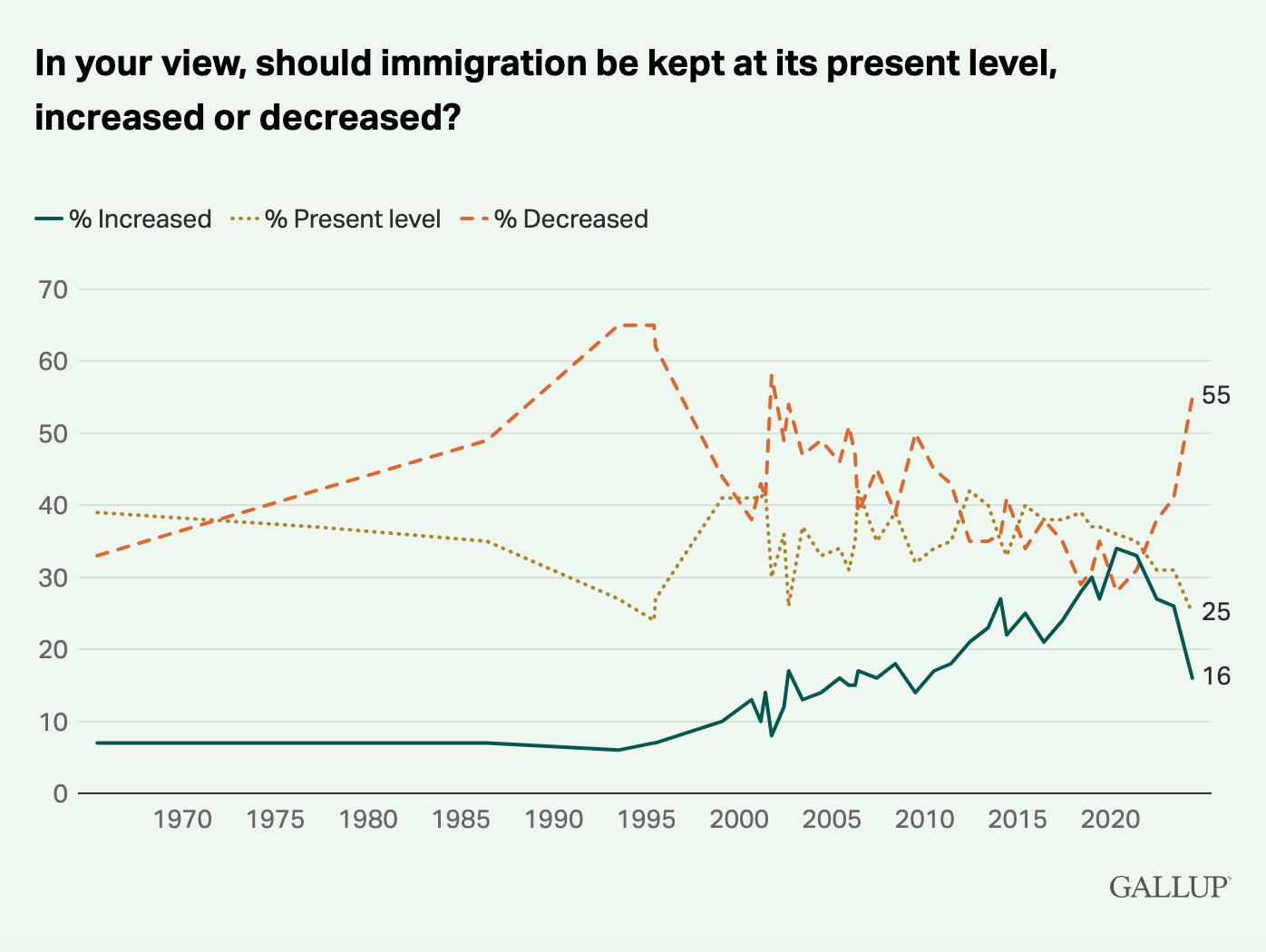

Perceived failure to address the continent’s troubles with immigration has clearly driven electoral politics elsewhere. The second-place finish of the restrictionist AfD in this weekend’s elections make the party Germany’s equivalent of France’s National Rally—a perennial opposition subject to a cordon sanitaire that makes forming a majority coalition nearly impossible. Restrictionist parties have been let into the government in the Netherlands and Finland, and are running the show in Italy and Hungary. And across the board, growing support for these previously marginalized parties is driven by European dissatisfaction with immigration—as evidenced, e.g., by the plurality of Germans who call immigration the nation’s most pressing problem. It should go without saying, moreover, that immigration played a major role in Donald Trump’s reshaping of the GOP, and his victory in last November’s election.

Part of what the Danes seem to have concluded, per Leonhardt, is that the socially tolerable level of immigration has declined. Consequently, in order to get democratic support for their other agenda items, they need to forego any progressive commitments they might have to higher level of immigration—or revise their progressivism (at least publicly) so that it is consistent with restrictionism.

There’s an implied view of immigration politics: more vs. less. Europe and the Biden administration turned the faucet on too wide; now, successful parties are those that want to close it, or at least reduce the flow.

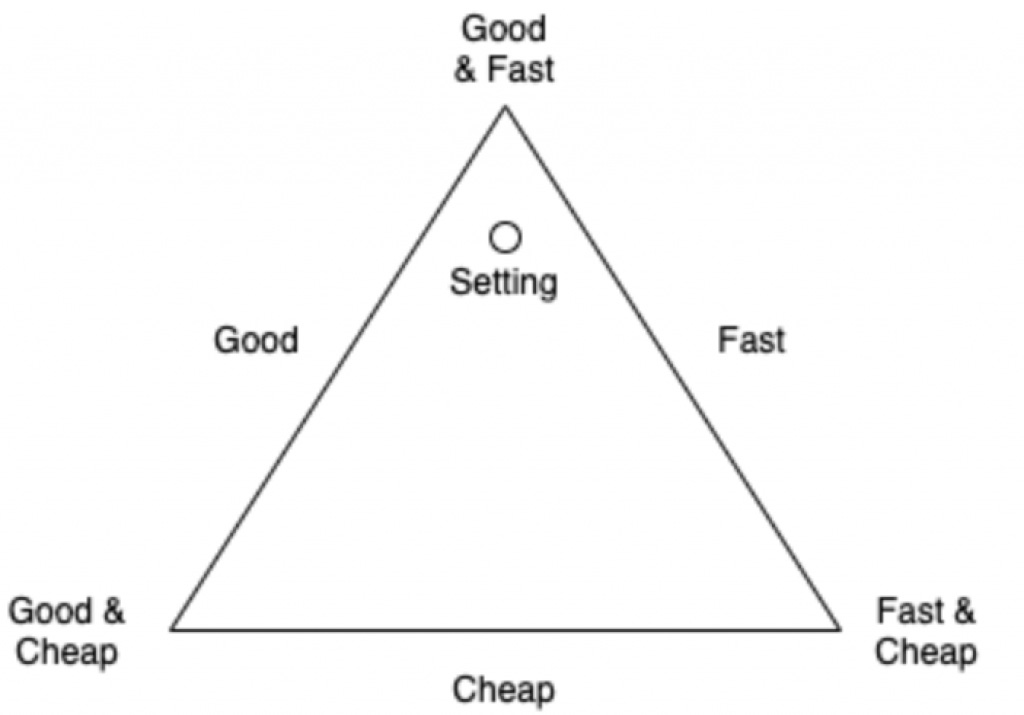

But that unidimensional model is the wrong way to think about it. Rather, I tend to think about immigration as an example of the principles of the engineer’s triangle in politics—an all-too-common way that optimization problems crop up in the policy space.

What’s an engineer’s triangle? It’s a concept in project management: for any given project, you can always choose two of “good,” “fast,” and “cheap.” That is to say: your project can be done quickly and well, but it will be expensive; it can be done quickly and cheap, but it will be poor quality; or it can be done well and cheaply, but it won’t happen fast.

Such three-sided trade-offs show up more often than you’d think in policy. My favorite example is health care: more free-market systems prioritize health care that is good and fast (but not cheap), while more socialized systems either prioritize good and cheap (in which case rationing is common) or fast and cheap (in which doctors are inadequately compensated to provide good care). of course, many systems barely hit one of these, but hard constraints mean that at the very best, you can expect to get two.

How does this play out in immigration policy? The answer starts with the insight that immigration has costs and benefits. On the one hand, immigrants generate economic value, create meaningful interpersonal relationships, and otherwise contribute to a flourishing society. They’re especially valuable in societies where declining fertility yields a greying population—through immigration, rich countries can steal poor countries’ young people. On the other hand, immigrants also add more people, who burden public resources, increase demand for scarce goods, and can introduce social harms like crime and disorder. Immigrants also increase diversity, which is both good (more ideas, more innovation) and bad (less trust, less ability to fluently coordinate).

These two sides tend to balance out, with research often finding no or small positive effects of immigration on average. But for every mean, there is a variance, and that average elides important heterogeneities. Some immigrants might be unusually productive, balancing out immigrants who are unusually harmful. Letting Albert Einstein immigrate is different from letting a triple homicide offender immigrate.

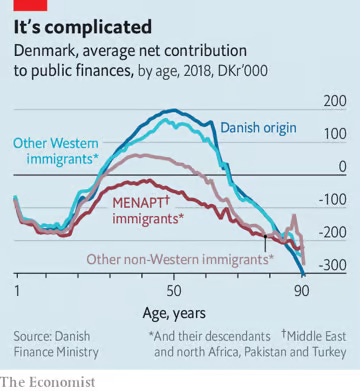

And impact varies along predictable margins. My MI colleague Daniel DiMartino has estimated that while immigrants to the U.S. are net fiscal contributors to the public fisc, all of the benefit is driven by arrivals with at least a college degree and under age 40 or so. Those below are net recipients, on average. Similarly, Denmark’s turn against mass immigration from the Middle East was driven in part by the insight that those arrivals, specifically, were net takers from the generous Danish welfare state.

There are non-economic costs, too. Many people—rationally or otherwise—feel a strong attachment to their received culture, and oppose disruptions that can come from being forced to share a nation with another culture. The European political experience demonstrates conclusively that you can’t shame the voting public into wanting more diversity—they have to be persuaded it’s good.

It’s possible to describe immigration systems that filter on the economic and cultural qualities of immigrants—call them “selective.” But many immigration systems are non-selective, which is to say that they don’t try to filter immigrants based on quality (where quality is some function of talent and culture fit/assimilability).

Selectivity matters because the costs of immigration can lead, and in Europe and the U.S. have led, to a reduction in public support for immigration. The public, importantly, is by no means a rational calculator—highly salient incidents like the murder of beautiful girls by recent arrivals can outweigh the fact that immigrants reduce crime rates, on average. But that is an unavoidable feature of living in a democracy: the public gets to run the country.

Which brings me, in a roundabout fashion, back to my engineer’s triangle. The three corners of our triangle are:

liberal democracy;

high rates of immigration;

non-selectivity of the immigration system.

Choose two—you can’t have a sustainable system that does all three. Why do I think of this as an engineer’s triangle? Work through some examples.

It’s easy, to start, to imagine a non-selective, high-rate system. Much of Europe has it, as (at times) has the U.S. But for a sustainable example, look to the U.A.E., where non-citizens make up 88% of the population. That large population does most of the labor for the 12% who are Emirati, and who reap most of the rewards. How does this work? Immigrants are brought in primarily for work, have few if any rights, and can be and are rapidly deported if they slip up. Moreover, the Emirates are non-democratic—if the population does not like this arrangement, they’re SOL.

But this sort of situation is not sustainable in western nations, where the public is in control, and where even non-citizens have often substantial rights and entitlements. The Danish response, then, represents another approach: preserve liberal democracy by simply lowering rates of immigration. The Sunak administration in the U.K. also made noise about doing this, and Trump’s aggressive enforcement agenda—which raises the cost of immigrating on average—is another variation.

There’s merit to this model. Level is much easier for policymakers to set, and they usually have a fair amount of executive discretion in its setting. Simply reducing quotas also clearly communicates to the public that you are listening. And you don’t have to get into thorny questions of selection if you preserve non-selectivity—just so long as you also lower rates.

But there’s a third side to our triangle: liberal democracy and high levels of immigration, combined with selectivity. That means a system which prioritizes immigrants that will be most-liked by the public—the greatest contributors, those who most easily assimilate—and which actively encourages immigrants to contribute and assimilate. Such a system ought to be able to sustain higher migration inflows over a longer period. In other words, the Danish model is to respond to the unpopularity of immigration by reducing the number of immigrants; another is to try to make immigration popular by getting better immigrants.

There’s reason to believe that voters would be receptive. While Americans have soured on immigration per se, high-skilled immigration specifically remains widely popular. Canada’s skills-based system sustained high levels of immigration with public support until Justin Trudeau dramatically increased the number of non-skilled arrivals.

Rather than cut quotas, western nations could shift to models that give top priority to the most skilled, assessed by market wage. And they could try to encourage assimilation by prioritizing native-language proficiency and minimizing cultural distance (optimized against skill), and by spreading immigrants out throughout the country, discouraging the formation of enclaves and encouraging out-marriage.

That approach is harder. In America, at least, it would require legislative change. And shifting to a selective system may require more delicate political messaging. Most challengingly, it involves conceding the idea that some immigrants are more desirable than others—a concept that has been anathema to both the open-borders left and the closed-borders right.

But it’s also probably a more sustainable balance for the west in the long run. After all, with fertility rates continuing to decline, human capital is becoming scarcer and scarcer. Cutting off the supply of high-quality immigrants in the name of taming electoral backlash will put these nations on the wrong footing in great power competition. Better to try to take those they can most use—and make immigration more popular in the long run.

A liberal dilemma on immigration is if a country can prefer immigrants from culturally similar countries. For instance, is it legitimate for a European country to welcome Ukrainian refugees but not refugees from other continents, whose culture is very different? Beyond differences in culture, can a country prefer "soft" cultural groups who do assimilate over "hard" immigrant groups that assimilate much less readily?

Interesting article. Of course, the one exception to this rule is Israel, which has been quite welcoming to low-skilled immigrants (Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews) in huge numbers in the past. But I guess that it’s an exception that proves the rule since it was founded as a safe haven for Jewish refugees. Not very egalitarian to admit smart and educated Jewish refugees but not dull and uneducated ones.

Israel still has open borders, but only for Jews and people of close Jewish descent (at least one halakhically Jewish grandparent). And even then, there has been some backlash in regards to this in Israel for allowing too many people who are not halakhically Jewish to immigrate to Israel, even though they actually do contribute to Israel, its economy, its budget, its society, and its military in a way that some other Israelis, such as the Haredim, do not.

Personally, I would prefer keeping liberal democracy while having more selective immigration in much higher numbers. We can also seek to make things fairer by using IQ testing for immigration purposes, not just educational credentials. At least that way we’ll be able to discover potential talent from Third World slums who didn’t have the opportunity or money to get fancy college degrees. But of course aiming for pro-natalism is also a good idea!

As a side note, in the past in the US, even some high-skilled immigrant groups, such as Chinese, Japanese, and Ashkenazi Jews, were not universally welcomed. But thankfully we appear to be a more tolerant society nowadays.