You Don't Have to End Homelessness To Make Cities Safer

Putting people in temporary shelter makes everyone better off, new study says.

Part of the problem with homelessness policy is that it spends so much time focusing on the homeless. There is, of course, a certain logic to this approach—after all, it’s in the name. But as my colleague Stephen Eide has argued, the term is something of a misnomer, collapsing a bundle of individual and social problems into a single issue, namely the lack of a house.

As a result, we often reduce the problems associated with homelessness to the question of how to get people a permanent home (in much the same way that we assume poor people’s problems stem from a lack of money). This is one way of explaining the “Housing First” theory of homelessness policy, which stipulates that people should be given permanent housing as soon as possible, regardless of their drug use, mental health, or other problems. HF advocates often look askance at more temporary or indirect solutions, which they see as getting in the way of getting people housed. (This is classic “root causes” thinking.)

Often absent from this debate is discussion of the social externalities of homelessness—public disorder, crime, all the topics I like to write about here. Sometimes these issues aren’t acknowledged, and those who insist on talking about them are tarred with various derogations. When they are acknowledged, the solution is often deemed to be getting people into permanent housing—i.e., making them not homeless—thus returning the discussion to the fundamental American problem of too little housing.

A new working paper from Stanford’s Derek Christopher, Mark Duggan, and Olivia Martin offers a rigorous intervention into this debate. It both demonstrates that unsheltered homelessness has real social costs, and challenges the idea that those costs are best, or only, remediable by getting people into permanent housing. It turns out that simply getting people into temporary shelter—often derided by the homelessness-industrial complex as a band-aid—significantly reduces both social and individual harms of unsheltered homelessness. Those harms, in other words, can be addressed without providing people with permanent housing—meaning that we don’t need to wait for the eternity that new housing requires in order to address them.

Christopher et al. focus on the effect of temporary shelter. Temporary shelter’s efficacy is, of course, often contrasted with that of permanent housing. As the authors note, “[p]roponents argue that [shelter] serves as a cost effective public good that mitigates the social costs of unsheltered homelessness, while critics assert that it diverts scarce resources from permanent housing solutions that more effectively reduce total homelessness.”

What are the social impacts of opening new shelters? To answer this question, the authors collected data from Los Angeles County’s homelessness system, crime data from the LAPD/LASD, and ER data from 2014 to 2019. They also use data on 170,000 unique individuals across 330,000 services check-ins to measure individual-level effects.

Why collect all of this data? In part, it’s because L.A. is a good context for studying homelessness: Los Angeles County is home to 3 percent of the nation’s population but 10 percent of its homeless population. But it’s also because of how the county approaches its problems. Every winter, it launches an expanded shelter program, temporarily adding 1,000 to 1,500 beds. The exact number of beds, opening and closing dates, and site locations all vary year to year. That creates exogenous variation that the paper exploits to estimate the causal effects of an additional shelter bed.

First stage: does the temporary expansion of shelter actually result in more people in shelter? Yes, the authors find—an additional 100 beds result in 89 additional people in shelter, “contradicting theories about widespread resistance to shelter among people experiencing homelessness.” They also find no corresponding increase in total homelessness, meaning that an increase in sheltered homelessness corresponds to a decrease in unsheltered homelessness.

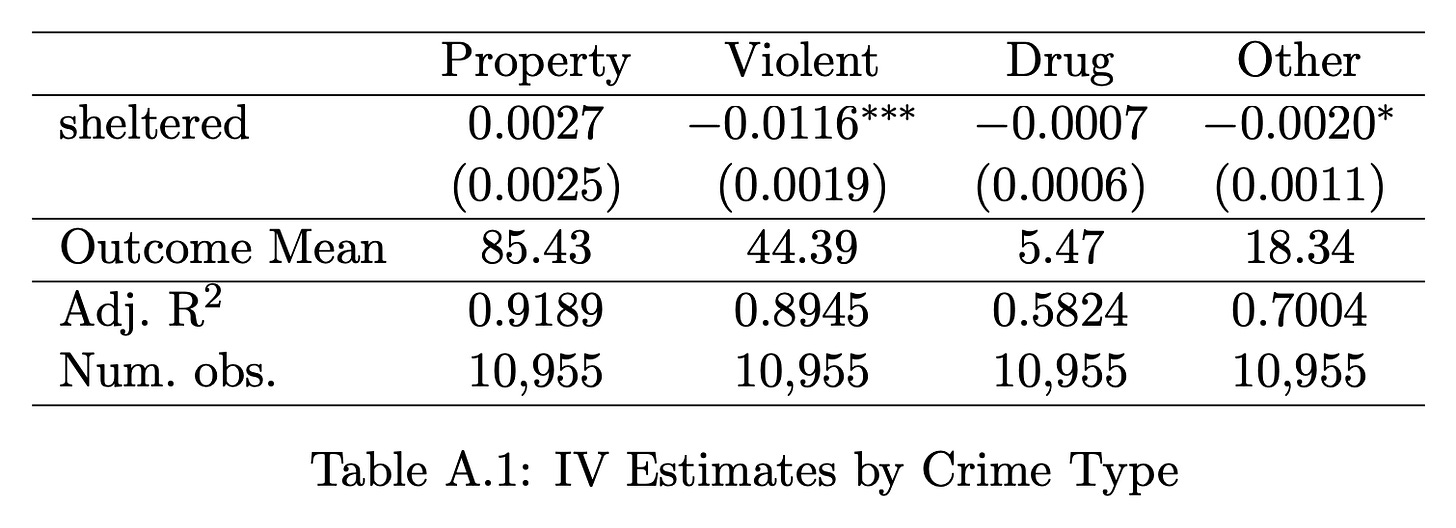

What does moving people off the streets in turn do? One thing it does is reduce crime—an additional 100 shelter beds prevent an average of 1 crime per day. These effects are driven by violent crime (as above) and are strongest at night, when the emergency shelters are open. The authors note that the effects could be driven by reductions in either victimizing or victimization—the homeless are often the targets of violent crimes, and giving them a safe place to sleep may reduce these offenses.

“At first glance, this [effect] may appear small,” the authors write. “However, during this period, LAHSA’s winter shelter program operates around 1,500 beds per day for roughly 4 months per year. So, in total, the program prevents nearly 15 crimes every day it operates or more than 1,500 crime incidents every year.”

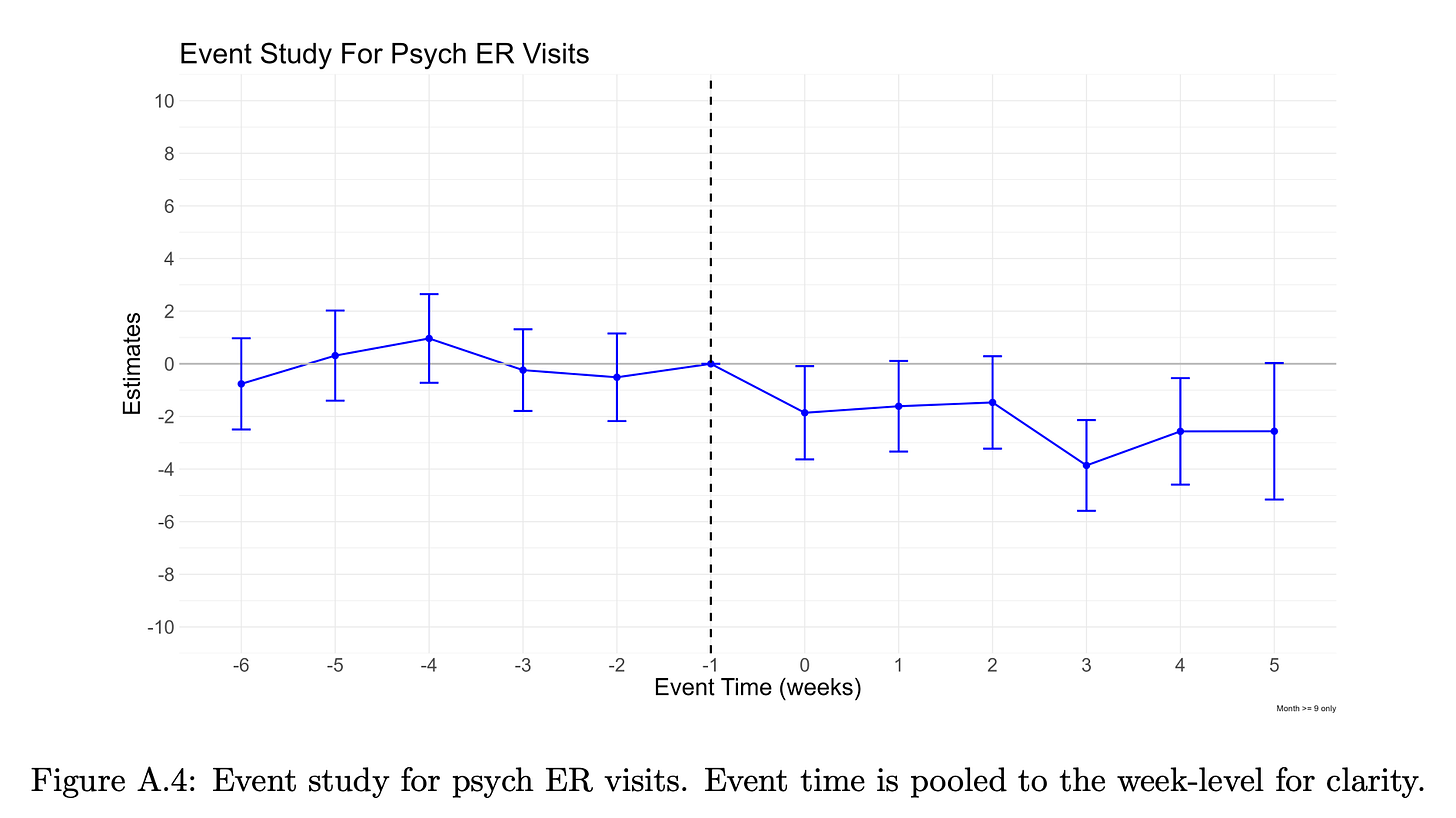

What about serious mental illness? The estimates imply that every 400 additional beds mean one fewer daily ER visit for psychiatric symptoms. Because temporary shelters don’t usually offer psych services on-site, this is likely the result of sleeping on the street being harmful to the mental health of occupants, and shelter mitigating that effect. The paper also finds suggestive evidence of a reduction in injuries and poisonings, “which are frequently referred to as the second most common reason for ER visits among homeless populations.”1

In addition to these estimates, the authors use data on individual homeless people to estimate the person-level effects of exposure to shelter. They find no effect of shelter availability on later usage of services, but there is evidence of a reduction in observed mortality (though that may be confounded by the process by which the data are observed.)

In other words: getting people into shelter reduces crime, ER usage for psychiatric issues, and (possibly) homeless mortality. As the authors put it, “temporary shelter functions as a high-value public good that generates substantial social benefits despite not ‘solving’ homelessness through permanent exits.”

There’s an interesting juxtaposition here, I should add, to the research on Housing First. Housing First does mechanically increase the likelihood of having a home: people who get Housing First stay housed longer. Conversely, however, Housing First has no effect on criminal offending or mental health outcomes relative to treatment-as-usual. Treatment-as-usual, in this case, is usually shelter, combined with whatever other patchwork interventions the jurisdiction supplies.

Read this in the context of Christopher et al., and the reasonable conclusion is that many of the problems associated with homelessness are the result of unsheltered homelessness. Give people somewhere to go—shelter or permanent housing—and the problem gets better. Having a lot of people on the street makes many things worse.

The argument then becomes entirely about cost. Unfortunately, today it costs a lot to build affordable housing. We can wait around for publicly funded permanent housing to be built, but it seems like it doesn’t actually do much to address the costs of homelessness. At the margin, shelter almost certainly buys you more bang for your buck.

This last point brings me back to how we think about homelessness and homelessness policy. Often the question we ask—including in the HF debate—is “how can we solve homelessness?” This is the motivation beneath expansive promises to end homelessness. We have spent tens of billions of dollars toward this end, with the result being that homelessness is about as bad as it’s ever been.2

But it turns out that you don’t need to “end homelessness” to address many of the serious social problems associated with unsheltered homelessness. You just need to get people off the streets. When you do, dysfunction goes down, even if you don’t resolve the “root causes” of the problem.

Poisoning presumably means ODs; confusingly, the poisoning estimate isn’t in the relevant appendix table, so I can’t verify that that’s right.

Which doesn’t mean we couldn’t significantly reduce homelessness. We could (by legalizing housing). Which I’m all for! But over here in reality, that’s unlikely to happen tomorrow.

Putting them in prison would also work, for certain values of "work". My understanding is that we (the social "we") aren't looking for policies that just "work", but for policies that will improve the situation for everyone involved, which is a much more difficult task. Which is the higher priority, the welfare of the "homeless", or the welfare of Everybody Else?

ToA, FST

Homelessness is exploding not declining. People need permanent shelter not temporary tent encampments or missions. Some studies have indicated it would cost around $20 billion to provide all homeless American citizens basic shelter. There are millions of homeless in the U.S. not hundreds of thousands as people living their vehicles or couch surfing are also homeless and one step from being on the street. We shouldn’t have any homeless whatsoever in the U.S: or any other wealthy country.