The Purpose of a System is What It Does

Review: Abundance, by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson

Review: Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance (Simon & Schuster, 2025, 288 pp.)

Abundance, the new and much discussed work from the NYT’s Ezra Klein and the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, is a book with two distinct visions. The authors would like to believe that these are, if not one and the same, then reconcilable. Unfortunately, they are not.

The first way to understand Abundance is as an intra-coalitional argument. Klein and Thompson are (they take great pains to remind us) liberals. And the book’s primary audience is fellow liberals, with the goal of galvanizing one side of an intra-liberal debate while chastising another.

In Klein and Thompson’s view, the liberal agenda is in conflict with itself. On the one hand, liberals want the state to deliver many goods and services efficiently and universally. They want health care and roads and houses and science funding and so on. Most importantly, they want the state to solve big problems: to fix climate change and disease and poverty and the rest.

On the other hand, liberals also want to regulate the processes by which these things are produced. They want to make sure that the housing is produced in a way that is not disruptive of community character, or doesn’t hand too much profit over to business. They want to make sure the solar panels are not constructed in a way that disrupts anyone’s view, or hurts endangered species. They want to distribute life-saving medication, but in a way that promotes racial equity.

Klein and Thompson think that liberals have leaned too heavily into this regulatory agenda, in a way that stifles the production of the things they want the state to produce. This position is obviously influenced by their experiences in California, a state where regulatory constraint has bottlenecked everything from housing to disaster relief. But they are informed also by the history of environmental and consumer-oriented regulation: the National Environmental Policy Act, Ralph Nader, Silent Spring, and so on.1

It is for this reason that many of Klein and Thompson’s left-wing critics (who are, bluntly, mostly operating in bad faith) accuse them of being crypto-rightists. Indeed, it is a little odd to read an explicitly progressive book that acknowledges, however obliquely, that the Endangered Species Act—one of the triumphs of 20th century liberalism—was probably on net a mistake.

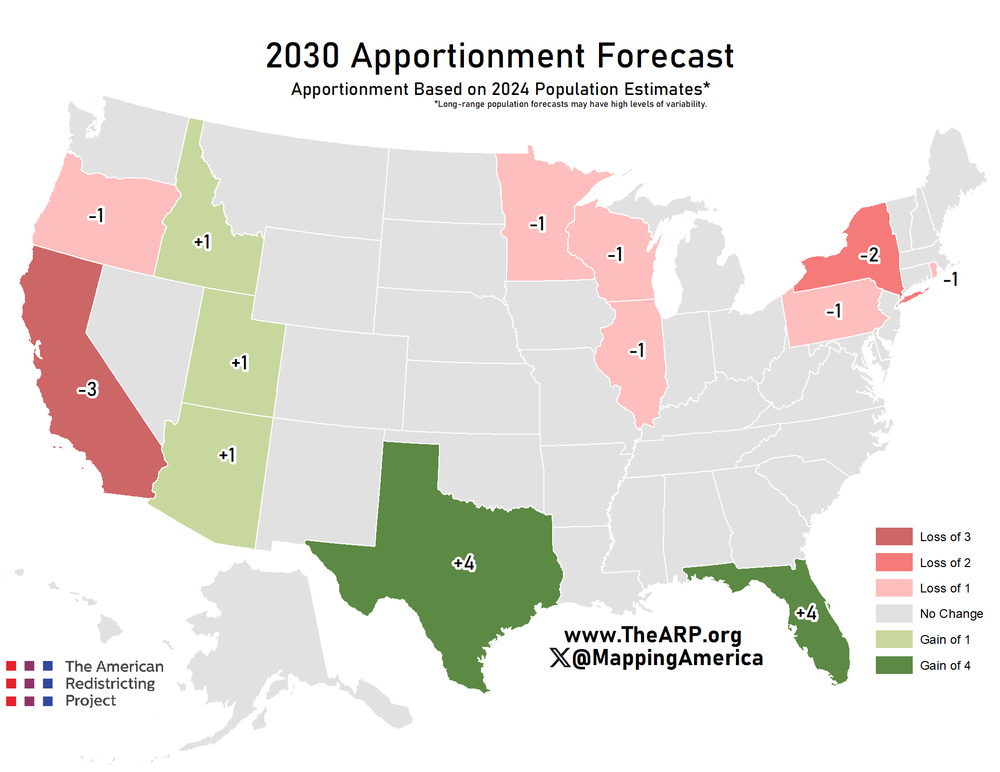

But another, more practical inference is that Klein and Thompson are hard-headed realists. There are political consequences to blue America’s “procedure fetish.” Many blue states are projected to shrink substantially by the next congressional reapportionment. This is thanks largely to out-migration driven in turn by sky-high housing prices and the comparatively low cost of living in low-regulation states like Texas and Florida. As a result, the Electoral College may be simply out of reach for a real progressive for a generation.

Which is not to say that Klein and Thompson are simply partisans. Rather, they recognize the fact that there are electoral consequences to refusing to build. And, more generally, they understand that if liberalism continues to get in its own way, it will do so at the cost of its legitimacy. If you want people to believe that government can provide results, government has to actually do it; if it can’t, then people won’t trust government.

This version of Abundance—a book about the idea that liberalism needs to get out of its own way—is fundamentally laudable. I am not in Klein and Thompson’s coalition, obviously. But I agree with many of their goals: I want more houses, more renewable energy, more scientific innovation, etc. And I am glad that someone from within their coalition wrote a book making their argument to fellow coalition members. I think America is a better place with a liberalism that wants to build than with a liberalism that wants to choke building off at the root. Abundance is a book that will get people talking about the right problems, and for that alone it deserves praise.

What I am not sold on, however, is the idea of a liberalism that builds.

This is the second way of reading Abundance: as a claim about what the state ought to do. When Klein and Thompson talk about a “politics of abundance,” they are envisioning a far more aggressive role for the state in the actual process of making things—of building—than it currently occupies.

To be clear, Klein and Thompson are not (contra their leftist critics) pure deregulators. Rather, they see deregulation as a means to increase output in the specific areas they are concerned about—green energy, housing, transit, etc. As Klein said on a podcast, “it’s not omnidirectional moreness. … I want more clean energy, not more dirty energy. If you come to me with a proposal for how we can build a shit-ton more fossil fuel plants, I am not excited about that. I will oppose you. … I am trying to define a set of goods and services and possibilities that liberalism … should get relentlessly focused on achieving.”2

Indeed, Klein and Thompson are happy to endorse the state being an affirmative contributor to the project of abundance. This is true not only in basic science, but also in construction. They’re not against government-constructed rail or public housing; they just want to reduce regulatory burdens that get in the way of those projects.

They seem to think, moreover, that the primary barrier to a liberalism that builds is in the realm of ideas. If they can persuade enough people that regulatory liberalism is getting in the way of the stuff liberals want, then there will be a deregulatory consensus, and we will all be better off. As is perhaps typical for journalists, they believe that political reality is determined by ideas, and that therefore they need to fight in the realm of ideas in order to win.3

But what if the problem isn’t a problem of ideology? What if it’s a problem of political economy?

Two years ago, Klein published an essay about what he termed “everything bagel liberalism.” (The essay is essentially repeated in one of the chapters of the book.) In it, he detailed the many roadblocks to construction of affordable housing in California. This he connected to liberalism’s habits of imposing too many constraints on its agenda, in an effort to put everything on the bagel:

You might assume that when faced with a problem of overriding public importance, government would use its awesome might to sweep away the obstacles that stand in its way. But too often, it does the opposite. It adds goals — many of them laudable — and in doing so, adds obstacles, expenses and delays. If it can get it all done, then it has done much more. But sometimes it tries to accomplish so much within a single project or policy that it ends up failing to accomplish anything at all.

I’ve come to think of this as the problem of everything-bagel liberalism. Everything bagels are, of course, the best bagels. But that is because they add just enough to the bagel and no more. Add too much — as memorably imagined in the Oscar-winning “Everything Everywhere All at Once” — and it becomes a black hole from which nothing, least of all government’s ability to solve hard problems, can escape. And one problem liberals are facing at every level where they govern is that they often add too much. They do so with good intentions and then lament their poor results.

This shows up in affordable housing, but also in—for example—the Biden administration’s signature legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act. As Klein writes, “if you read through the text of the I.R.A., you will find quite a few goals in competition. The climate side of the I.R.A. pairs investments in decarbonization with buy-American rules and labor standards and much else.”

You could view this ever-growing stack of requirements as the result of good intentions gone awry. But that assumes that otherwise savvy political actors are simply making foolish mistakes. Why? Why, exactly, do all of these requirements—zero-carbon, union-made, respect for local interests—get piled on top?

There’s a phrase from systems thinking that gets used frequently on Twitter X: “the purpose of a system is what it does.” As coiner Stafford Beer put it, there is “no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.” The liberal state constantly fails to build. Why should we think that’s what it’s supposed to be doing?

Rather, a better way to understand the everything bagel phenomenon is as coalition management.4 It’s not that the IRA got passed or public housing gets built in spite of the giveaways and procedural requirements layered on top. It’s that the IRA got passed or public housing gets built because of the giveaways and procedural requirements layered on top. The pay-offs to and carveouts for unions and local agitators and everyone else exist because that’s how you make sure things actually get done. In their absence, those people exercise the vetos that are inherent to the state building in a democratic society.

The idea generalizes. The fact that California spent billions of dollars without producing usable high-speed rail (a favorite foil of abundance liberals) can be viewed as an accident. But it is more parsimonious to say that California succeeded at its goal—allocating billions of dollars to innumerable contractors and private interests—and, incidentally, some train tracks were eventually constructed.

In fact, it is possible to model the entire state of California this way. Many California progressives ask how the state can simultaneously be so innovative and rich and also be so besotted with regulation, corruption, and graft. But of course, California is actually so dysfunctional because it is so rich—there is a great deal of wealth available to be siphoned off and used for less-noble interests.

The purpose of a system is what it does. What the state does is impose restrictions on building, mostly for the benefit of special interest groups. There is no point in claiming that the state is there to build when it constantly fails to do so.

Does this mean the state can’t build? Not precisely. But it does mean that the state building looks very different from private enterprise building. In order to build in a democratic5 state, you need someone who can successfully wrangle all the interests that are formally and informally entitled to vetoes if they don’t get their pay-off. You need extreme executive agency—akin to, or greater than, what you see in the private sector.

Successful state building looks like, well, Robert Moses. Moses successfully built New York not in spite of graft and corruption, but through it. He built using the strategic application of patronage, which he seized for himself and applied to the purpose of building. As I wrote in my review of The Power Broker:

Moses was personally honest with money—primarily because every time he got some, he used it to get more power. He handed out millions of dollars in retainers and insurance fees to favored politicians, and used the money that flowed into his authorities to tie together “banks, labor unions, contractors, bond underwriters, insurance firms, the great retail stores, [and] real estate manipulators” in support of his vision.

But most bureaucrats are not Robert Moses.

When Moses is finally pushed out of power, by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, he still commands the support of the city’s labor unions, because they realized that nothing of the Moses scale could be built without Moses’s organizational capacity. Democracies are made up of many, often diffuse, centers of power. If you want to get something done, sometimes you need executive agency to bring those together.

In the absence of a Moses-like executive—which is the state of most actual existing democracies—these diffuse centers of power vie to extract as much as they can out of any given public-work project. Why wouldn’t they? It’s there for the taking, isn’t it? And the purpose of a system is what it does.

America, in fact, is uniquely ill-suited to the strong executive model of building. It is not an accident that European nations—with their strong states and traditions of minimal rights—build more than we do. But even there, the building does not actually translate into growth. Many Euro-zone nations’ real GDP per capita has been essentially flat since the Great Recession. Yes, their trains are very nice. But it is hard to think that their system is actually conducive to building as such.

Against this backdrop, it’s worth asking why, exactly, we should want the state to build. After all, the private market is quite good at growth. Yes, we should get the government out of its way. But we should certainly not regard the state as an effective substitute.

Frustratingly, the American liberalism that Klein and Thompson oppose themselves to is the American liberalism that understood that government is bad at building stuff. A fancier term for a liberalism that doesn’t build is “neoliberalism.” It is the liberalism of the Clinton era, a liberalism based on the insight that markets do better at most things than government, and government should focus on being the safety net underneath the market and a check on its worst behaviors.

Klein and Thompson’s vision, by contrast, is synonymous with the liberalism that Clinton et al. had to abandon in order to win. What is a liberalism that envisions a more aggressive role for the government in building things? Let me quote from another, older abundance liberal:

Your imagination, your initiative, and your indignation will determine whether we build a society where progress is the servant of our needs, or a society where old values and new visions are buried under unbridled growth. For in your time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.

The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning.

That, of course, was Lyndon Johnson at the University of Michigan in 1964, announcing his Great Society agenda.

Johnson’s agenda, though, created not abundance, but dysfunction and sclerosis. And it was eventually responsible for a great many of the laws and regulation that Klein and Thompson see as getting in the government’s way. That wasn’t an accident—it was intrinsic to trying to bring the production of abundance under the aegis of the state, in turn creating veto points and the incentive to build more of them.

So while I applaud Klein and Thompson for acknowledging that regulations are getting in the way, while I would be very happy to have them as the opposite pole of American political life, I still think they are fundamentally misguided. Great Society liberalism has been tried and found wanting. And it is so because its results are the necessary consequence of the state trying to get into the building business.

Which is not to say the state should not get out of the way in the ways Klein and Thompson enumerate. It absolutely should. But it should rarely—and only cautiously, and where absolutely necessary—get involved in the way they want. Far better to let the market do the building—which is, at current margins, what Klein and Thompson want anyway.

A “politics of abundance” is an oxymoron. Politics is for the divvying up of the fruits of actual productivity, sometimes well and sometimes poorly. To ask it to do the work of production is to miss what it is for.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, well, read the book.

If you are concerned by all the ellipses here, listen to the clip. I think this is a faithful distillation.

Obviously, I also believe this on some level; otherwise I wouldn’t be writing this Substack. And I do not think this view is always wrong. I just think it’s wrong here.

The Democratic Party is actually all about coalition management, because it’s a coalition of interests, whereas the GOP is an ideological vehicle. Interestingly, I think there’s a real possibility that this dynamic flips, as the Trump coalition makes the GOP into a durably ideologically divided party. But the ideology that will come to dominate the Democratic Party in that exigency is, uh, not going to be Klein and Thompson’s.

You can definitely circumvent a lot of this if you’re a vicious autocrat who can just kill people who get in the way. But I think it’s safe to say that Klein, Thompson, and I are all against that.

I don’t find all of this convincing. The ability to build a good transit system *does* predict GDP growth, and the link is state capacity to build things and enforce rules. There’s a reason that the countries that put together the state capacity to build or enforce rules are rich. There is no requirement that you can only be good at some subset of things that require state capacity. There is no trade off, there is only gain from doing the job better.

Trying to improve that capacity, and reorient government and political processes, aims to improve the same core state competence that you help push for and Ezra/Derek are getting at.

I want to give you two concrete examples.

1) It now seems clear that Red States are going to adopt universal school choice and Blue States are going to do the opposite (in fact are going to require a degree of ideological managerial control in schools that surpasses anything I grew up with). This is a huge difference between the "state capacity" and "free market" view on one of our societies biggest and most important sectors.

2) I personally have a front row seat to the IRA. I will give you a review of my sector:

1) The CBO score on the IRA was an outright lie and everyone knows it was an outright lie.

2) The IRA claims it saves money while at least increasing cost by 300%.

This matches earlier special interest giveaways I've observed in my career in healthcare.

The Democratic Party is ultimately an Eds and Meds lobbyist group backed by single and government employment (and adjacent) women. It's not going to build. That isn't what the base wants (the base isn't male policy wonk nerds that think they are philosopher kings that should rule).

I FULLY ENDOSE what Ezra is trying to do, and think the world would be a better place if he wins his intra party debate.

But I also advised my nephew in California to move to Florida, because I just don't believe in Ezra at a fundamental *goals* level. I think the state should shrink, not grow.