Disorder! At the Starbucks

On third places, and why disorder matters

Like anywhere from a quarter to half of Americans (depending on who and how you ask) I work remotely. My employer, the Manhattan Institute, is in Manhattan (obviously). I live outside of Washington, D.C., mostly for contingent reasons. In theory, I could work at my home, but I have no home office, and also there’s a baby there a lot of the time. Consequently, I spend a lot of my day at coffee shops, and especially at Panera Bread.1

A lot of people go to Panera in the middle of the workday. There’s a retirement home nearby, and you get a lot of elderly people and their adult children. There’s an adult daycare program for people with mental disabilities that stops in pretty frequently. There’s a group of ladies who play mahjong on a monthly basis. People take meetings there. You know the deal.

Panera is, in other words, what sociologists refer to as a “third place”—a space that is neither home (first place) nor work (second place). Third places are public. They are intended to be used by everyone, whether because tax dollars fund them (as in parks and community centers) or because that creates revenue for the owners (as in coffee shops). It is permissible for people to not merely stop in, but occupy them—assuming they share the space fairly with everyone else.

Because third places are open to everyone, sometimes they have problems with disorder. (Remember: disorder is domination of public space for private purposes.) Sometimes people come into Panera and start panhandling; sometimes they scream and yell; sometimes they take over the bathroom and make a huge mess. I work at a suburban Panera, so we don’t get a lot of ODs, but they happen sometimes at other Paneras.

One of the common responses to people’s concerns about such disorder is to ask why anyone really cares. People who worry about disorder, as someone over on Twitter claimed recently, are really just cowards. They don’t know how to put up with someone making a scene. Suck it up!

And to be fair, when someone starts panhandling at Panera, I don’t freak out and leave; I just politely say “no, sorry” and go back to what I’m doing. But it does make my day more unpleasant: if I sprung for the We Work, I wouldn’t have to put up with the messy bathrooms or the occasional yelling. It’s not irrational for disorder to be part of my, and others’, decisions about whether or not to use third places at the margin. Unpleasant experiences are costs, too.

How much should we care, though, if people choose not to use public space? When people talk about “third places,” it’s often in the sort of touchy-feely terms that make me roll my eyes. A characteristic defense in The Atlantic describes third places as conducive to “spontaneity” and “purposelessness,” and blames their decline on “culture obsessed with productivity and status.” The implication is that third places have no instrumental value—that indeed, they’re good because they don’t.

This is, of course, all very nice (although frankly to me it reeks of a desire to return to the college dorm room). But it does not explain why policymakers should care about third places, or about the disorder in them. Why does it matter, beyond our individual enjoyment, if public spaces are disorderly?

Which brings me to Starbucks.

Starbucks (in case you live under a rock) is America’s largest chain of coffee shops, worth over $100 billion at most recent valuation. Part of the company’s success came from the fact that, unlike other coffee chains, it has focused on selling itself as a third place. CEO Howard Schultz actually used the term in a 2004 annual report. People go to Starbucks not just to buy coffee, but to have meetings, read, and otherwise exist in a place that is neither work nor home.

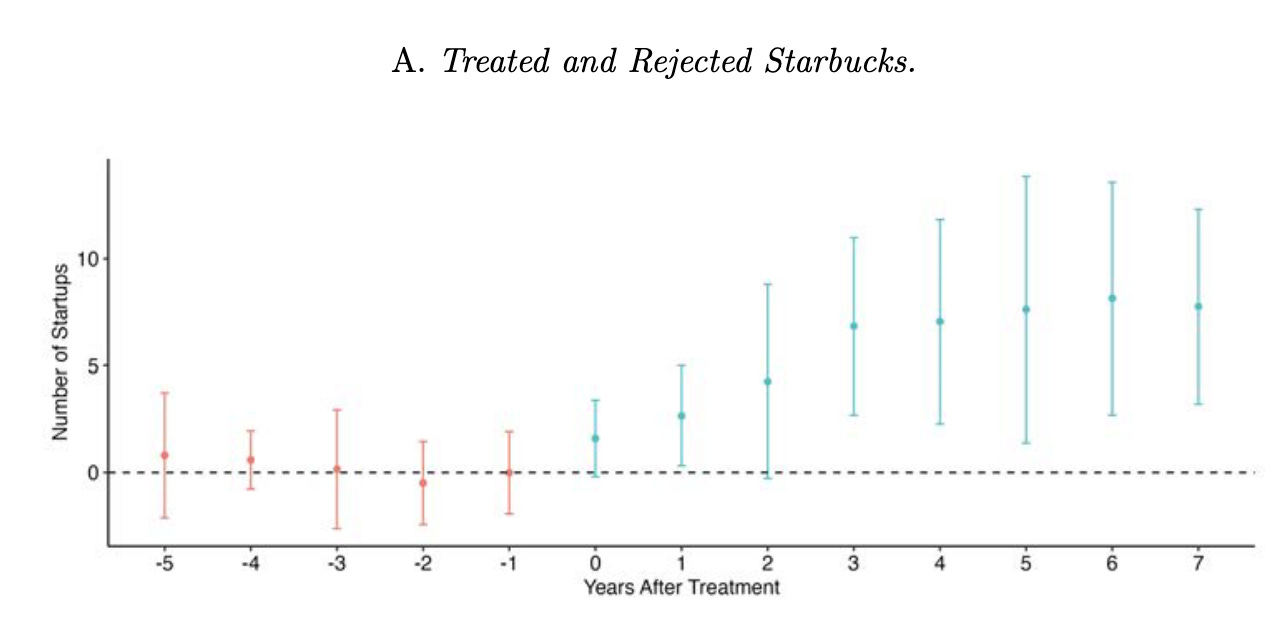

Which raises an interesting question: what does adding a Starbucks—as a kind of third place—do to a neighborhood? In a recent working paper, economists Jinkyong Choi, Jorge Guzman, and Mario Small (hereinafter Choi et al.) investigate this question. They measure the location of Starbucks openings between 1997 and 2021 at the Census tract level (approximately the size of a neighborhood). Then, they use several natural experiments to estimate the effects of an opening on the rate of formation of start-ups—a measure of entrepreneurship generally. In particular, they compare tracts that receive a Starbucks to those that did not due to some administrative issue; look at underprivileged tracts that received Starbucks thanks to a partnership with Magic Johnson; and look at tracts where Starbucks was the first entering coffee shop.

The results are quite stark: in all three specifications, the opening of a Starbucks leads to a large and significant increase in the number of startups in the neighborhood. Comparing tracts where a Starbucks was opened to one where it was blocked, the cafes increase firm formation by an estimated 12 to 18 percent. In Magic Johnson tracts—which are underprivileged, largely minority communities—a Starbucks creates 30 to 36 percent more start-ups, equivalent to between 4 and 6 additional businesses in the tract per year.

Why does this happen? In supplementary work, Choi et al. show that Starbucks with higher levels of foot traffic and more space lead to greater levels of start-up formation. As the authors write, “it is precisely those establishments that offer the features conducive to an effective third place, such as opportunities for a high level of local interaction and the open space to do so, paired with a large number of visitors, for which we see large increases in neighborhood entrepreneurship following their opening.”

To put this more simply: opening a Starbucks in a neighborhood creates start-ups in that neighborhood. And that’s because Starbucks acts as a third place, creating opportunities for felicitous connection and fruitful cooperation. After all, if you want to meet and talk about a business idea, but you don’t have an office yet, where do you go?

The idea that Starbucks create start-ups is just a (particularly well-supported) instance of the insight that public space is conducive to economic flourishing. Indeed, one of the major insights of urban economics is that cities produce disproportionate levels of innovation in part because they create opportunities for collaboration. Public space is essential to that collaboration—good fences make good neighbors, but very bad start-up cultures.

Which brings us back to disorder, and why policymakers should care about it. Disorder raises the costs of using public spaces; at the margins, it encourages people to use them less. No one wants to go to the Starbucks where people are overdosing in the bathroom.

Maybe this all has an unpleasant aesthetic tone to you; maybe you are mood affiliated away from start-ups, which are “bro-y” or whatever. “Why should I care if people are starting Uber for salsa?” you might ask.

The answer is that it’s not just start-ups. It’s collaboration of all kinds—that’s what cities are good for. And disorder is harmful because it gets in the way of that process; it makes cities less healthy, and less productive for the rest of society. Disorder imposes costs not merely on people’s experiences, but on the productivity of cities and society.

Policymakers need to care about that. They should care about it locally because businesses create tax revenue, which is the life blood of a city. But they should care about it also because they want everyone to be better off. And consequently, they should be willing to do something about disorder not merely because no one likes it, but because it gets in the way of what makes cities tick.

Why Panera? Because for $120/year, you can get unlimited coffee, wi-fi, and somewhere to sit. It’s a cheap man’s We Work, in my opinion. Full disclosure: I am writing this post at Panera right now. (Yes, I have tried the lemonade that kills you. It’s fine.)

Good article but I was hoping this would look into what the effect of the "no purchase necessary" era of Starbucks has been ever since they were shamed into letting people sit around / use the bathroom without making a purchase. Has this hurt sales? Starbuck's ability to serve as a third space? Startup formation? Good test as to how much disorder really matters.

I agree 100% My concern is when this kind of valid local concern get weaponized to elect politicians at the national level that want to raise tariffs, cut taxes and cause deficits and deport long established immigrants.