Why I Am Not Optimistic About Declining Overdose Deaths

It's probably not anything we did, and it may get worse again

If you’ve been following the drug news,1 you may have noticed a flurry of headlines over the past several days heralding a long-awaited decline in the overdose death rate. The original article is from NPR, which appears to have gotten an exclusive on the latest release from the CDC’s Vital Statistics Rapid Release system (now available for everyone here).

The trend does look, as NIDA director Nora Volkow put it in a gushing quote to NPR, “very, very real.” The above chart is both the VSRR data and data from the CDC’s WONDER database, which I’ve included to give a sense of the longer term trend. (Both are based on the same data source, i.e. death records submitted to the CDC.) In both data sets you can see a big drop which seems to have started in the winter of 2023. NPR says it expects a steeper decline through the rest of 2024.

It’s going to be hard to say what’s going on until we have richer data, which won’t be for a while. That said, I’ve had a few people ask me for my thoughts; I’m writing them here to organize them as much as anything else.

Synthetically: while I’m glad the measured rate is declining, I think the optimism this report has generated is misplaced, and possibly irresponsible. There is very little reason to think we’ve gotten a handle on the fundamental determinants of the drug crisis, and much reason to think that the reversion we’re seeing is a function of trends largely beyond our control. If things are going right, it’s not because we’ve made them go right—which means they can and will go wrong again.

What Can We Say About What’s Going On?

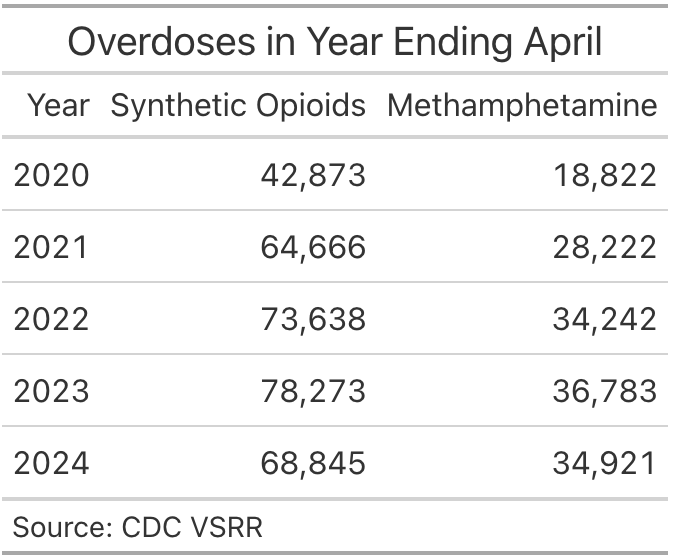

Aggregate trends like the one depicted above can elide important compositional differences. There are two dimensions I can look at in the VSRR data: geography and the drug involved in overdose. Historically, these have varied in important ways. One fact about the drug crisis is that it has consistently spread east to west. Another is that (to a first approximation) surplus drug overdose deaths are either from synthetic opioids (principally fentanyl, either pure or adulterating e.g. cocaine) or methamphetamine.2

Both of these problems seem to have gotten better in the year ending April 2024 (the last month in VSRR). But synthetic opioid deaths have declined more, in absolute and percentage-wise terms, than have methamphetamine deaths.

This is probably related to the geography of overdose deaths. I said earlier the drug crisis spreads east to west, but that’s not precisely true. More specifically, synthetic opioids spread east to west, while methamphetamine spread west to east. Synthetic opioids are deadlier, so the aggregate effect is east to west. But if the drug crisis is cooling more in the east than the west, then we should expect synthetic opioids to be coming down more than meth.

That geographic distribution is indeed what we see, at least at the level of total OD deaths.3 In the chart above, there are a number of states where there was a downturn in late 2023/early 2024. But there are also states, mostly in the east, where the downturn predates that period (look at Indiana, West Virginia, and sort of Ohio—notably all early OD hot spots). More importantly, we see states, all in the west, where ODs are still climbing or haven’t started dropping (Washington, Oregon, Idaho, California, Nevada, Wyoming, Colorado, etc.).

How can we think about what’s going on here? As I’ve argued many times before,4 the exponential increase in drug overdose deaths represents a transition in the drug supply to synthetic drugs, which are much cheaper, more potent, and deadlier. States underwent that transition at different times and, in particular, the west coast has been delayed in the transition. The east seems to have hit some critical point, but the west is still ramping up. The fact that some hot spot states experienced the decline earlier further suggests that there’s some local maximum—although not necessarily a global one.

Dying Now/Dying Later

One mental model of what’s currently going on in overdoses is that we’ve hit a peak and are now going to decline to some much lower level. Drug crises tend to go in waves; maybe, after 20+ years of increase, rates of OD death are finally going to start precipitously dropping.

Maybe! But there’s an influential 2018 paper (2022 follow-up) which observes that OD deaths have been rising on an exponential curve more or less continuously since 1979. There are waves in the trend, but the steady underlying rate of increase reflects (in my opinion) exactly the technological shift I’ve been talking about.

What happens if we apply that insight to recent trends? The figure above shows the actual CDC WONDER data, compared to an exponential curve fit to the 1999 - 2019 data. What we see is that the growth in deaths was more or less on trend until early 2020, at which point there was a sharp upwards deviation. The recent decline is, if anything, a return to the underlying trend.

I don’t want to talk about why there was a sharp uptick in 2020. (Mumble mumble COVID George Floyd mumble mumble.) Instead, I want to make the point that such deviations from trend are, in some senses, self-correcting, and that a sharp decline is what we should expect to see after a sharp rise.

The way to think about this is to imagine a stock of people who use drugs regularly enough to be at risk of overdose death. Every year, some number of people are initiated into drug use, and every year some number of people die, thus dropping out of the pool.

What appears to have happened in 2020 is a large and sustained surge in deaths—a big increase in the rate at which people drop out of the pool. But, to put it in somewhat morbid terms, if a person died in 2020/21, he wasn’t “available” to die in 2023/24. A big burst in drug ODs, caused by some exogenous shock, should be followed by a return to the baseline rate, simply by virtue of this dynamic. What this implies, moreover, is that the decline we’re seeing is “paid for” by deaths we saw earlier—many of those people who “should be” dying now are already dead. And we’re trending back towards the baseline—which is, of course, a long-run exponential increase.

It’s Probably Not About Policy

What I’ve argued to this point is that the decline is a) not uniform across places, but varies in important ways, and b) probably represents a return to some underlying trend, rather than an about-face/end to the current crisis. This is a way of arguing more generally that the aggregate trend we’re seeing is a function of changes in non-policy variables, rather than some sudden success on the part of state, local, or federal governments. NPR quotes Volkow as attributing the decline to “expansion of naloxone and medications for opioid use disorder — these strategies worked.” I think this is unlikely. Here are a few reasons why:

The geographic patterns in OD death rates do not seem to obviously correspond to any harm-reduction or treatment policy intervention. Individual states have tried a variety of policy interventions, and states with varying policy approaches followed similar trends.

Conversely, the between-state variation suggests that federal policy cannot have had much impact. Any federal policy that reduced ODs in, say, Massachusetts probably should have reduced ODs in California. Maybe it did, cet par, but not enough to show up in the aggregates.

The temporal pattern—a sudden drop off in late 2023/24—does not correspond to any obvious change in the policy environment. Zach Siegel, a drug-policy journalist, correctly notes that there’s been non-trivial federal policy change. But most of that change significantly predates the downturn. To explain a big drop in late ’23/early ’24, we’d need some corresponding big policy shift.

We also have a great deal of evidence that the sort of policy Volkow is talking about does a poor job reducing overdose deaths. I don’t want to review it all here, so I’ll just highlight the recently published results of Communities that Heal, a four-state, 67-community study that saw treatment communities implement hundreds of strategies, focusing on “overdose education and naloxone distribution … the use of medications for opioid use disorder … [and] prescription opioid safety.” The study got glowing coverage … which was stupid, because there was no statistically significant difference in overdose related deaths between treatment and control communities. (Jon Barron has a good write-up here.)

It’s possible, of course, that there’s been some supply-side intervention that’s had a radical effect. But the border crisis continues to rage, and drug seizures at the border are not appreciably off trend. If the Mexican cartels had been shut down, you think we’d have heard about it.

In other words, not only are the data not consistent with a policy-driven explanation; we also have very recent evidence that barraging communities with scattershot harm-reduction and treatment interventions does very little to reduce OD death.5 And we have no reason to believe that there’s been some big turnaround in interdiction. So the most parsimonious explanation is that something other than policy has caused the change.

The Drug Supply Is Getting Weirder

There’s one last angle to all of this that I want to highlight: part of what’s happened over the past several years is that the drug supply has gotten weirder. NPR actually acknowledges this, writing:

The chemical xylazine is also being mixed with fentanyl by drug gangs. While toxic in humans, causing lesions and other serious long-term health problems, xylazine may delay the onset of withdrawal symptoms in some users. Dasgupta said it's possible that means people are taking fewer potentially lethal doses of fentanyl per day.

I’ve written here at TCF about xylazine, the animal tranquilizer that’s being added to the fentanyl supply throughout the east coast, before. The Dasgupta point is a good one: xylazine has all sorts of nasty side effects, but if it reduces the frequency with which people are dosing (much more potent) fentanyl, it might on net reduce ODs. Chris Moraff, another drug-policy journalist, made a similar point on X the Everything App (tm):

@ShawnWestfahl and I called an impending drop overdoses almost 2 years ago when proportions of Xylazine to fentanyl started increasing.. tranq causes all manner of problems but death is rarely one of them

The thing is, it’s not just xylazine. We’re still in the early stages of the emergence of nitazenes, which the DEA helpfully defines as “an emerging synthetic opioid group that can be more potent than fentanyl and poses an additional opioid threat to the United States.” There’s also all sorts of other weird adulterants. One recent paper identifies the spread of Bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate, an industrial additivie, in the drug supplies of four different states. Another animal tranquilizer, medetomidine, is also spreading.

What this reflects is that the drug supply is only getting weirder. As the cartels that produce for the U.S. market get better at sourcing and synthesizing different additives, the diversity of substances will only grow. In some cases, like xylazine, additional weirdness may yield reductions in overdose deaths. In other cases, like the nitazenes, it might increase it.

Either way, though, there is very little reason to rest easy. It’s good that OD deaths dropped. But I don’t think it’s because of anything we did. And there’s every reason to think things will keep getting weirder—and possibly worse—in the future.

and if you haven’t, why are you reading this Substack?

I know this chart is hard to read. You can right click and expand it. But you don’t really need to care about the levels, just the trend lines. And those are quite visible. Also, this super cool map style is made with the geofacet package in R; thanks to MI data analyst Matias Ahrensdorf for reminding me which one I was thinking of.

The best summary of my views on the issue is this National Affairs essay.

This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t use these interventions. I kind of think the problem with Communities that Heal was that it just threw a bunch of stuff at communities, rather than hyper-targeting people. But that’s another post.

I believe fentanyl is never used in pure form but always mixed with filler. What if fentanyl manufacturers/ packagers have improved their quality control such that a single pill will never have enough fentanyl to cause an accidental overdose? And IV users will have access to better controlled potency less likely to cause accidental overdose?

It never stops being weird that the NIDA director is Trotsky's great granddaughter though I guess no weirder than Stalin's granddaughter running an antique shop in Portland.