Your Revolution is Over, Mr. Lebowski! The Bums Lost!

Social policy, moral equivalence, and the 2024 election

If you watched the election returns last night, you probably paid attention to the big stuff. Most Americans were tuned in for the Presidential match-up. A smaller share (presumably) were watching to see how the Senate came out or, at least, the House of Representatives.

Not me, though.1 I was watching to see what happened with Massachusetts Ballot Question 4, the “Natural Psychedelic Substances Act.” You see, some Massachusetts residents got it into their heads that they should both decriminalize and create a legal framework for the sale and administration of certain “natural” psychedelic substances. Part of the reason that they believed this was a good idea is that Oregon and Colorado had already made moves in this direction, creating legalization frameworks for magic mushrooms specifically. Legalization in Massachusetts was just the next step in a bigger campaign to move psychedelics into the Overton window.

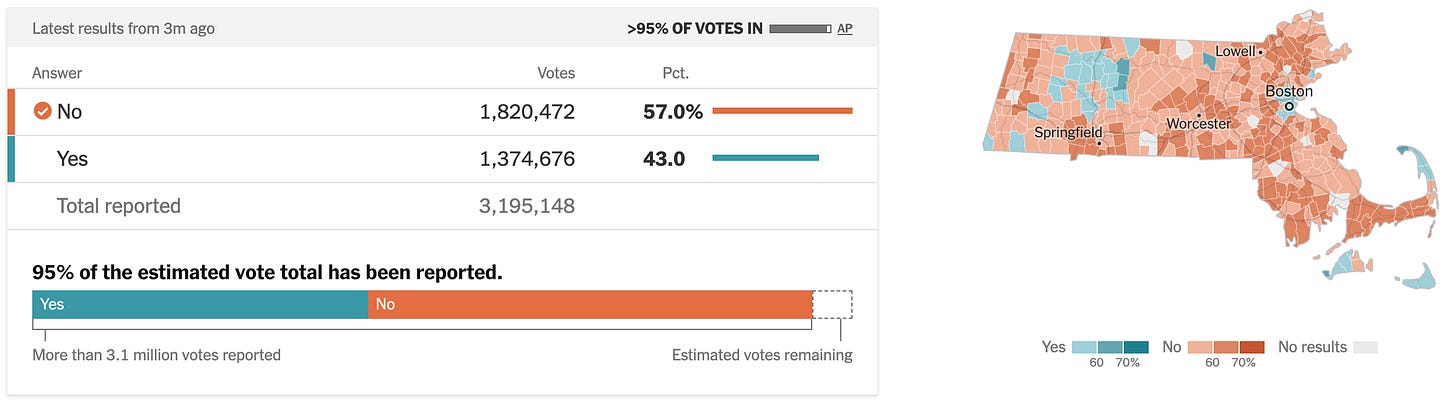

I’ve written about why this is a bad idea (see my WSJ op-ed). And the polling said things might go my way, but the margins would be razor thin. But—as with other races—the polling was wrong. Bay Staters resoundingly rejected “natural medicine,” by a 14-point margin in the most recent data. Yes on 4 could barely swing a majority in Boston (53 percent yes) and Cambridge (57 percent). Perhaps signifying their desperation, Graham Moore, the educational outreach director for Yes on 4, tweeted “BREAK THE LAW” in the late hours of last night.

That kind of lopsided result was not restricted to Massachusetts, though. Yes, it happened at the top of the ticket. But across a variety of ballot initiatives and referenda you may have missed, progressive social policy came in for a drubbing:

Amendment 3, Florida’s recreational weed legalization initiative, fell short of passage. Voters in North and South Dakota also resoundingly rejected legalization initiatives.

California’s Proposition 36 (which I wrote about last week) was passed by a margin of more than two-to-one.

Arizona’s Proposition 314, which lets the state enforce immigration laws, also passed almost two-to-one.

Progressive prosecutors George Gascon (Los Angeles), Pamela Price (Oakland, Calif.), Deborah Gonzalez (Athens, Ga.), and Andrew Warren (Tampa, Fla.) all lost reelection.

These votes follow other major state-level changes over the past two years: the end of drug decriminalization in Oregon and British Columbia, the recall of Chesa Boudin in San Francisco, and of course legal decisions like Grants Pass.

It’s easy to dismiss these votes as corrections of progressive excess, which is itself thereby implied to be accidental. But I think they are more fundamental: a repudiation of a tendency which had major influence between about 2014 and 2021, which rears its head in American politics every few decades, and which remains extremely important in the policymaking arena.

After all, most of these votes are repudiations of prior political acts. Question 4 was an extension of the campaign for psychedelic legalization that had already won in two states (and a handful of cities). Prop. 36 was meant to undo Prop. 47, while Prop. 314 was a response to federal policy priorities. Progressive prosecutors are a deliberate move to change the balance of interests in the criminal justice system. Drug recriminalization follows decriminalization. And so on.

You could say they are repudiations of progressive excess. But I think the “excess” is really the policy instantiation of a specific idea: that the costs of deterring antisocial behavior exceed the benefits, in large part because the interests of the antisocial ought to be treated as equivalent to everyone else’s.

Because, of course, the behaviors we are talking about are antisocial—if they weren’t, we wouldn’t care to regulate them. Criminal conduct is antisocial, of course; so too is, as I’ve argued, public camping. But drug use can be, too, whether it’s the social costs imposed by temporary inebriation or dysfunction. Yes, it is fun and perhaps even fulfilling to do shrooms, but the fraction of users who go crazy from them will impose their craziness on the rest of us.

The arguments for drug decriminalization, or progressive prosecution, or the rest, sometimes hinge on factual disputes (“marijuana isn’t really addictive!”), but those are often just (on both sides) pretexts for normative disputes. The real argument is that even if these behaviors are harmful, it’s not fair or worthwhile to deter them, because the costs of doing so are too high, or because it contravenes some (usually ungrounded) natural right to do so.

The archetypical case of this way of thinking might be Christopher Glazek’s unusually honest 2012 n+1 article, “Raise the Crime Rate.” Glazek’s argument is, in essence, that the great crime decline of the 1990s and early 2000s was paid for by mass incarceration, and specifically by the suffering of the incarcerated.2 This transaction is taken to be unjustifiable, because the people on the inside are people too, and their suffering should have equal moral weight to those on the outside. Consequently, we should be willing to dramatically reduce the use of incarceration. As Glazek writes, “you cannot relieve the suffering of the prison population without increasing safety risks for the rest of us. And increasing those risks, from a moral standpoint, is the right thing to do.”

You can apply this logic across the spectrum of social policy pertaining to the regulation of anti-social behavior.3 Yes, maybe the guy sleeping on the corner or the guy blowing smoke in your face are making your life a little worse. But it isn’t fair to stop him from doing those things; it hurts him more to do so than it hurts you to let him do so.

When Glazek wrote that piece, he was part of the early rise of a major social movement. That movement argued that America had gone too far in its exercise of social control in the 1990s and 2000s, and that the consequences had been devastating, a “New Jim Crow” that had destroyed the lives of millions. Social control—the imposition of standards of conduct on our society and consequences for people who fail to adhere to them—had too high a human cost, even if it made our lives and our cities nicer.

This is the argument that, for a moment, carried the day in 2020. But it was not then a novel argument. It was present, at least in places, in the 2010s. It showed up in reformist movements of the 1970s, and arguably in left-libertarian strains stretching back for centuries.

But it is also the argument that was comprehensively repudiated at the ballot box on Tuesday—in the initiatives identified above, but also, yes, by some of the tens of millions of Americans who voted for Donald Trump.

The source of their disagreement is not foolishness or bigotry. It is the fundamentally correct judgement that people like Glazek are wrong, specifically because the interests of deliberately antisocial people do not deserve equal weight to everyone else’s. The problem with Glazek’s moral calculus is not the assumption that every crime prevented on the outside is counterbalanced by a harm on the inside (though this is probably also nonsense). The problem is the idea that a bad thing happening to an innocent individual is of equal moral weight to a bad thing happening to a guilty one, that injustice and consequences are of equal significance. The costs of making sure that everyone plays by the same rules are not equal to the costs imposed by those who break the rules, because the two acts are morally different.

What Americans said on Tuesday is that their patience with such moral equivalency is up, has, indeed, been up for years. We are happy to be a generous nation—we are, arguably, the most generous nation on Earth. But we are uninterested in being hectored for not wanting to be generous to those who take advantage of that generosity. We want to live in a society where people follow shared rules, not where dysfunction is taken as something worth protecting, even celebrating.

That, I think, has substantial political implications. It means that voters will continue to punish the Democrats—apparently quite severely—for their willingness to countenance such ideas at all.

But it also means that they want a right that speaks to these issues coherently, not merely with platitudes about “law and order” but with real policy solutions for making our communities safer, more orderly, and more functional. (I would be remiss here if I didn’t note that I work for an organization that is interested in exactly this set of problems, and how the right can address them in a more coherent fashion: manhattan.institute.)

The bid is in; whether either side will take it is another matter altogether.

I mean, yes, obviously I was watching the top of the ticket. But you don’t care what I think about that, and I don’t think my opinions are interesting enough to write down. So bear with me.

This is empirically wrong—mass incarceration explains at most something like 20% of the crime decline. Actually, the thing that probably drove much of the crime decline is policing! Which, as a bonus, also reduces criminal offending and thereby incarceration. Deterrence is the magical solution to the problems of both the innocent and the guilty. But for some reason we don’t talk about that nearly as much as why we need to let murderers out to maximize utils.

Which, I mean, is the area of social policy I work on, so if you’re not interested in it, read a different Substack.

For another Glazek type argument in the wild, see Phil Cohen's post in which he argues that we should accept immigrants that have criminal backgrounds *for the other nations safety*, https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2024/09/29/you-know-whats-really-migrant-crime-trump-and-ice-and-people-who-know-better-should-explain-this-stuff/.

Getting the costs and benefits of policing/social control of disorder is an ongoing process. COVID seems to have encouraged/empowered people to engage in more anti-social and outright criminal behavior --murder to low muffler noise.