Cynicism Is Not a Mode of Policy Analysis

Responding to Freddie deBoer

Freddie deBoer does not understand drug policy. He is, as far as I can tell, only tenuously familiar with the topic. He certainly does not have informed opinions on it. Like many people, this does not stop him from opining on the issue. But that does not make the opining any more insightful.

I base these assertions on the reply to my Ezra Klein appearance deBoer wrote over on his Substack.1 From that essay, I learned that he believes things such as:

Fentanyl is an “oral opioid” (I mean, you can technically ingest it, but people overwhelmingly inject or smoke it);

The drug crisis was caused by stable heroin users switching to “oral opioids” (actually they went from ingesting prescription opioids to heroin, not the other way around);

“Decades of analysis” support the Iron Law of Prohibition (no, not really, and he doesn’t produce any of this analysis);

“Legalization” and “decriminalization” are the same thing (they aren’t; the former means creating a regulatory infrastructure for a drug, while the latter just means removing criminal penalties, and I have no idea which one deBoer favors).

These may see like petty objections. But they get to the bigger problem with deBoer’s critique, which is that he has substituted a kind of world-weary cynicism for any actual understand of what drug policy does or ought to do. This is not unique to him; he’s just recapitulating popular leftist arguments about drug policy. But it is useful to review the arguments he makes to explain why those arguments are wrong. Cut through the extraneous insults and unwarranted assumptions, and you charitably get an argument something like this:

Prohibition has no effect on the potency of drugs;

Prohibition is also very bad and harmful;

Actually, no policy can have an effect on the potency of drugs because;

“human beings want to get high, have always wanted to get high, and will always want to get high”;

everyone who disagrees is just a utopian fool who lacks deBoer’s firm grounding in the subject matter.

Obviously all of these points are wrong, for reasons I have mostly already articulated on this Substack and elsewhere. But let’s dig in.

Prohibition Has no Effect on the Potency of Drugs

DeBoer’s approach to proving this point is, as far as I can tell, to Google “potency of” plus the name of the drug, grab a chart, and observe that the line goes up. For example, here’s the one he dug up from rehabs.com.2

The line goes up over the period, even though the substance is prohibited. Therefore, prohibition has no effect on potency.

Astute readers of TCF can probably already guess the issues here, but I’ll list a few:

Changes in potency that happen exclusively under prohibition cannot be ascribed to prohibition, because prohibition does not change over the period. That is to say: if you are arguing that prohibition has an effect, you need to have a period in which prohibition is not in effect to compare to.

Relatedly, the bar by which we judge prohibition is not “are drugs at 0% potency” but “are they less potent than the counterfactual of legalization?” I find it hard to believe that meth would be less potent if it were sold by Wal-Mart, and I say this because the meth actually distributed by pharmacies is much purer than street-grade product.

If potency rising under prohibition is caused by prohibition, then surely potency falling under prohibition is too. Here is another deBoer-Googled chart showing declining heroin purity. Thanks, prohibition!

There’s no actual reason to select potency as the only, or even the most important, effect of prohibition. Why are we not talking about number of users, or extent of overdose deaths, or addiction rate, or whatever else?

Fine, okay, deBoer’s method of inference amounts to observing that, in spite of prohibition, line go up. What he’s trying to do (while claiming not to) is defend the Iron Law of Prohibition. As I wrote last month, the Iron Law of Prohibition is probably real, insofar as it’s just an application of the Alchian-Allen theorem. But its effects are swamped by the Iron Law of Liberalization: free-market innovation means that the more liberal the drug laws, the more potent the drugs. Yes, potency can rise and fall under prohibition. Prohibition is good because it means that drugs aren’t maximally potent, super cheap, and widely available.

But do we have evidence that prohibition and/or enforcement can affect drug harms, other than lines going up? Yeah, obviously. Here’s a sampling:

Cunningham, Liu, and Callaghan 2009: U.S. precursor controls targeting large-scale producers probably substantially reduced purity relative to counterfactual.

Hsiang and Sekar 2019: the temporary legalization of the sale of ivory in China and Japan led to an increase in black market poaching, because permitting a market to operate leads to an uptick in demand and therefore supply.

Moore and Schnepel 2021: the Australian heroin drought, a dramatic reduction in supply to Australia, probably reduced opioid user mortality by about 2%.

Porreca 2024: a large scale takedown operation in Kensington, Philadelphia created “large declines in overdose mortality in the Philadelphia metropolitan area as a whole, suggesting a genuine reduction in the demand for illegal narcotics.”

What these papers show is that prohibition and enforcement can have effects on drug harms. The fact that they do not set the level of potency to 0—or whatever other measure of harm you prefer—does not obviate this fact.

DeBoer does, to his credit, observe something interesting: potency has tended to rise inexorably over the past several decades, across substances. This he labels a failure of prohibition, but I actually think it’s a vindication of it. That’s because systematically rising potency is a function of innovation in the drug market(s)—drug traffickers have gotten better at making purer and purer product.

But the question is not why they’ve done that, but rather what’s taken them so long. Humans have known how to make fentanyl for sixty years; why did it take traffickers until the mid-2010s to start replacing heroin with it? The answer, more or less, is that prohibition makes the diffusion of innovation slow, faltering, and expensive. In a commercialized legal drug market, businesses would have been able to sell fentanyl over the counter to consumers at their whim. Prohibition has not stopped completely the increase in potency. But it has made it much slower, and saved a lot of lives in the process.

Prohibition is Also Very Bad and Harmful

DeBoer doesn’t actually make this argument in the sense of citing facts to prove a point, but he does issue a denunciation:

For example, at one point Lehman suggests that’s what’s necessary for marijuana decriminalization to work is very harsh enforcement against the black market trade; that is, the legal market can’t compete against the black market, so you have to have particularly muscular enforcement against the black market. What he doesn’t say, and what Klein doesn’t bring up in response, is that very harsh enforcement of the black market in a larger decriminalization environment entails all of the ills of drug prohibition that we’ve lived with for too long - locking people up for possession, taxing our criminal justice system in an inevitably doomed effort, deepening racial inequality and the destruction of already-impoverished communities, and dramatically expanding the infrastructure of the drug war, which already amounts to one of the most horrifically misguided wastes of blood and treasure in the history of the country.

DeBoer of course misses my point: when you legalize a substance, you have reduced the non-enforcement effects of prohibition in suppressing the market. Consequently, you have to do more enforcement to obtain the same suppression of the remaining illicit (i.e. unlicensed) market place. This is politically unpalatable, because you just spent years insisting, as deBoer does, that prohibition is evil and mean and bad. So you don’t do it, and the grey market flourishes. “That very harsh enforcement of the black market in a larger decriminalization environment entails all of the ills of drug prohibition” is exactly why people don’t want to do enforcement. But as a result, you cannot control the licensed market. This is why 60% of marijuana is still sold on the illicit market, even though a majority of Americans live under state legalization.

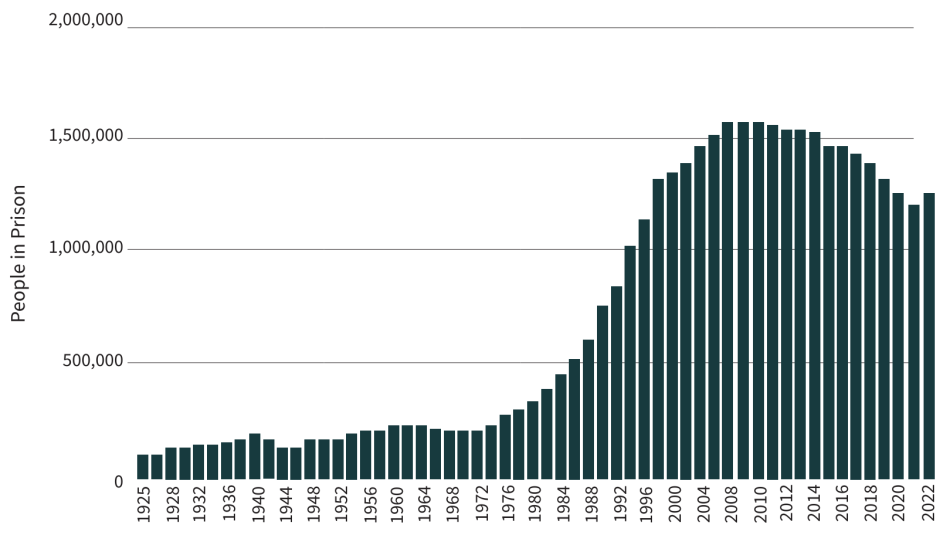

But this gets to a bigger point, which is that deBoer is confusing “prohibition” with “the War on Drugs as conducted in the 1980s and 1990s.” But U.S. drug policy has varied widely throughout the century we’ve lived under prohibition. For example, the period of extremely low incarceration levels identified above coincides with prohibition. So does the period of extremely high ones!

I tend to think that while its evils are overstated, the War on Drugs was not a policy success. I have written rather a lot on this; for perhaps the most thorough treatment I have published, see this paper. Succinctly: there are rapidly diminishing marginal returns in the effectiveness of drug enforcement, for extremely straightforward supply-and-demand reasons. That means that enforcement-forward, or enforcement-only strategies, like the ‘80s/’90s War on Drugs, will have relatively little impact.

That doesn’t mean you do no enforcement. It means you need to be much smarter and more targeted about enforcement, to think about non-police enforcement, and most important to prioritize treatment and prevention. (I have written a lot on that, too.) Most importantly, you don’t end prohibition, which among other things stops legitimate businesses from getting involved in the sale of addictive, harmful substances.

So, I suppose I agree that an extremely bad version of prohibition is bad. Prohibition has costs and benefits, and you need to optimize those. But there is a broad policy space—one in which many, many jurisdictions, in the U.S. and elsewhere, have operated—between throwing people in prison for twenty years for an ounce of pot3 and legalizing all drugs.

Incidentally, in a line familiar to TCF fans, deBoer claims:

We know, in fact, that criminalization does not reduce overdose deaths and probably increases them.

No, we don’t know that. The evidence out of Oregon is consistent with either no effect or an increase; the Portugese evidence points in several directions, but could be read as consistent with an increase. The study deBoer cites probably just shows that cops do more enforcement following overdoses. My general read is that criminalization probably has no effect on OD deaths over the short run, which is fine, because the problems with decrim (as opposed to legalization) are much more about the harms attendant to public drug sales and use.

But deBoer doesn’t think we can reduce OD deaths through any other means either. Which brings me to:

Actually, No Policy Can Have an Effect on the Potency or Harms of Drugs

And, specifically, we can’t do demand-side interventions either. deBoer writes:

There was a period of time when that bit of wisdom was used to justify a demand-side approach to the drug problem. That is to say, since we can’t stop the economic power that ensures supply, we have to stop demand. Rather than defeating drug abuse through securing the borders and hunting down the traffickers - who would inevitably be replaced with a new trafficker, as there’s always a new cartel waiting in the wings - we would defeat drug abuse through rehab and education, attacking the problem at the demand side. The problem, it turns out, is that you can’t stop demand either.

This is an argument that advocates of drug legalization like to make. They point out that many people relapse, pointing especially to the high relapse rate following detox. This, they say, is a reason to shovel funding into their unaccountable NGOs fund “evidence-based” harm-reduction interventions, and stop wasting time on trying to treat people until they’re maximally ready to accept treatment.

This is measurably false. Most people recover. We have evidence-based interventions, both pharmaceutical and behavioral, that significantly increase their probability of doing so. People can in fact be prevented from initiating use. DeBoer writes about the level of drug use as though it is constant, but it rises and falls over time. This is a function of both cultural and policy inputs, which are in turn related to each other.

Frankly, it’s pretty bizarre that the guy who thinks we ought to force the mentally ill into treatment doesn’t think drug treatment works. I would rebut the evidence he offers for this proposition, but he doesn’t offer any except his dad’s personal struggle with alcoholism. I’m very sorry that that was his experience. But that’s not a basis for policy making.

Human Beings Want to Get High, Have Always Wanted to Get High, and Will Always Want to Get High

This is something that advocates of drug legalization say that they think sounds insightful but that is in fact largely meaningless. Yes, sure, “people want to get high.” Drugs are fun, they feel good, and people have been using them for a long time. I do not believe, and no serious supporter of prohibition believes, that the level of drug use can be reduced to zero.

But if we take this position seriously, it amounts to the view that the demand for drugs is short-run and long-run perfectly inelastic. No matter what you do, people will continue to demand the exact same level of product. This is, of course, completely false. The most recent meta-analytic estimates suggest that demand for drugs is slightly inelastic, about 0.9. Demand among addicts is much more inelastic, but a) it’s not 0, b) behavioral interventions can alter it, and c) because people can be deterred from initiating drug use (partially by suppressing the market), many people who would become addicted do not, which is one of several reasons why long-run elasticity is higher than short-run.

Once we frame deBoer’s argument in terms of supply and demand, moreover, we realize how ridiculous it is to say that policy cannot affect drug consumption. As I’ve argued before: regulation affects both supply and demand in any regulated market, reducing equilibrium quantity and/or increasing equilibrium price. This is true of kale, milk, pornography, cigarettes, alcohol, and heroin. It’s actually quite important for it to be true for deBoer’s other preferred policies—he is, you know, a socialist—to work. Prohibition is a kind of regulation. Yes, sure, people want to get high. But prohibition can and does make it harder for them to do so.

Everyone Who Disagrees is Just a Utopian Fool

I have admittedly been a little harsh in this reply. In part, this is because I don’t enjoy being condescended to about drug policy by prominent commentators who have a demonstrably limited grasp on the topic. But it’s also because I find deBoer’s style of argumentation to be typical of the far-left view on drugs, insofar as it substitutes a kind of world-weary cynicism for any actual policy insight. As he writes:

Lehman is the perfect example of a type that you’re more likely to find among utopian leftists but which exists across the political spectrum: the guy who always says “Hey, we can do better than this.” Klein, as perhaps the quintessence of the sunny liberal wonk who thinks he’s smart enough to pull all the right levers, of course feels the same way. And we all have to have the integrity to say, actually, Charles, Ezra, sometimes we can’t.

The implication here is that, of course, I disagree with deBoer because of some moral failing: I am a utopian who lacks integrity, whereas he really gets what’s going on. But cynicism is not actually a mode of policy analysis, and insults are not a substitute for knowledge of the issues. Yet, for some reason we continue to act like they are. We take seriously people who affect a world-weary posture, as though this is an actual source of information.

I can, I suppose, understand why people do this. Most policy interventions fail. Getting things right is extremely hard. But doing nothing—doing … whatever it is that deBoer wants to do—is not a neutral choice. As Mark Kleiman observed, in drug policy you can either have the harms of drugs or the harms of prohibition. Throwing our hands in the air and declaring the problem hard isn’t insightful. It’s vacuous.

It’s paywalled. I’m not going to endorse paying for it, but if you want to read it instead of just trusting my quotes, I guess you can.

These data can be found in the National Drug Threat Assesment, or in STRIDES directly, but in order to know that you’d have to have a passing familiarity with this issue area. But I digress.

not that that is a thing that happens regularly.

Drug policy is not the only topic in which FDB is ill-informed.

There is a reason I call Freddie deBoer "Freddie daHater" on MattY's substack. For every salient observation he makes he makes two asinine statements that makes you slap your forehead.